Automating the Cloud: The Rise of AI Agents in Linux System Administration

The Next Frontier in Linux Automation: AI-Powered Agents

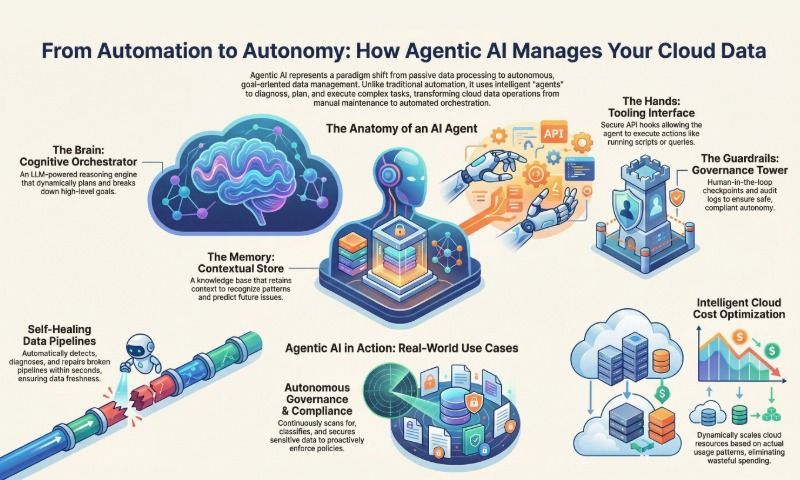

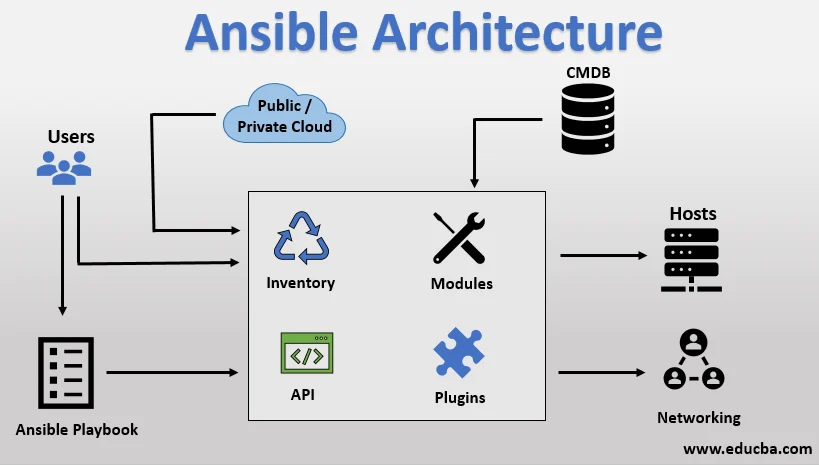

For decades, Linux system administration and DevOps have been defined by a relentless pursuit of automation. From simple bash scripts to sophisticated configuration management tools like Ansible, Puppet, and Terraform, the goal has always been to make complex infrastructure manageable, repeatable, and scalable. Today, we stand at the brink of a new paradigm shift, one fueled by the rapid advancements in Large Language Models (LLMs). This evolution is giving rise to a new class of tools: autonomous AI agents capable of operating directly within a Linux cloud environment. This is a major development in Linux cloud news, promising to redefine how we interact with our servers and manage our infrastructure.

Unlike traditional automation, which follows a rigid, pre-defined script, these AI agents can interpret natural language commands, reason about multi-step problems, and interact with a Linux system’s command-line interface (CLI) to achieve a goal. Imagine telling an agent, “Diagnose why the web server is slow and apply a fix,” and watching it analyze logs, check resource utilization with htop, and restart a service—all without manual intervention. This technology, while still nascent, has profound implications for everything from routine maintenance on Debian and Ubuntu servers to complex incident response in enterprise Red Hat environments. This article explores the core concepts, practical implementations, and critical security considerations of using AI agents for Linux cloud administration.

Core Concepts: How AI Agents Interact with the Linux Shell

At its heart, an AI agent operating in a Linux environment is a program that follows a simple but powerful loop: Observe, Think, Act. It uses an LLM as its “brain” to process information and make decisions, and it interacts with the system through the same tools a human administrator would: the shell.

The Observe-Think-Act Cycle

- Observe: The agent gathers information about its environment. This could be the output of a command like

ls -l, the contents of a log file fromjournalctl, or the status of a systemd service. - Think: The agent feeds this observation, along with its primary goal, into an LLM. The LLM analyzes the context and decides on the next logical step. For example, if the goal is to “check disk space” and the observation is a command prompt, the LLM’s thought process might be, “I need to run the

df -hcommand.” - Act: The agent executes the action decided by the LLM. This almost always involves running a command in a shell, such as

bashorzsh. The output of this command then becomes the new observation for the next cycle.

This loop continues until the agent determines that the initial goal has been achieved. The magic lies in the LLM’s ability to break down a complex request into a sequence of simple, executable Linux commands. This is a significant step forward in Linux automation, moving beyond declarative configurations to goal-oriented, dynamic execution.

Let’s look at a very basic, conceptual implementation in Python to illustrate this interaction. This example uses the subprocess module to execute a shell command, simulating the “Act” phase of an agent.

import subprocess

import shlex

def execute_linux_command(command: str) -> str:

"""

Executes a Linux command safely and returns its output.

This function represents the 'Act' step of an AI agent.

"""

if not command:

return "Error: No command provided."

# Use shlex.split to handle command arguments properly and avoid shell injection

try:

# We use text=True to get stdout/stderr as strings

# and capture_output=True to capture them.

# check=True will raise an exception for non-zero exit codes.

result = subprocess.run(

shlex.split(command),

check=True,

capture_output=True,

text=True,

timeout=30 # Add a timeout for safety

)

# Combine stdout and stderr for a complete observation

output = f"STDOUT:\n{result.stdout}\nSTDERR:\n{result.stderr}"

return output.strip()

except FileNotFoundError:

return f"Error: Command not found: {command.split()[0]}"

except subprocess.CalledProcessError as e:

return f"Error executing command: {command}\nExit Code: {e.returncode}\nOutput:\n{e.stdout}{e.stderr}"

except subprocess.TimeoutExpired:

return f"Error: Command '{command}' timed out after 30 seconds."

# --- Agent's "Thought Process" (Simulated) ---

# Goal: "List the files in the current directory with details."

# LLM's Decision: "The best command for this is 'ls -lh'."

# --- Agent's "Action" ---

chosen_command = "ls -lh"

observation = execute_linux_command(chosen_command)

print(f"Executing command: '{chosen_command}'")

print("--- Observation ---")

print(observation)This simple script forms the foundation of an agent’s ability to interact with any Linux distribution, from Arch Linux on a developer’s machine to AlmaLinux in a data center.

Building a Practical Linux Agent with LangChain

To move beyond a simple command executor, we need a framework to manage the agent’s state, memory, and decision-making process. LangChain is a popular open-source library that provides the necessary tools for building sophisticated agents. A key concept in LangChain is the “Tool,” which is a function the agent can choose to use to interact with the outside world.

We can wrap our execute_linux_command function into a LangChain Tool. This gives the LLM-powered agent a specific capability: running shell commands. The agent can then decide when and how to use this tool to accomplish its objectives.

Setting up the Environment

First, you’ll need to install the necessary Python libraries. This setup is standard for Python Linux development.

pip install langchain langchain-openai python-dotenvYou will also need an API key from an LLM provider like OpenAI, stored in a .env file for security.

Creating a Command-Line Tool for the Agent

Now, let’s create a more robust agent that can reason about which commands to run. This example demonstrates how to give an agent a single tool: the ability to run shell commands. This is a foundational step in creating agents for Linux server news and administration.

import os

import subprocess

import shlex

from dotenv import load_dotenv

from langchain.agents import tool, AgentExecutor, create_react_agent

from langchain_openai import ChatOpenAI

from langchain import hub

# Load environment variables (for OPENAI_API_KEY)

load_dotenv()

# --- Define the Tool the Agent can use ---

@tool

def execute_shell_command(command: str) -> str:

"""

Executes a shell command on the Linux system.

Only use this for safe, read-only commands like ls, cat, df, uname, etc.

Do not use commands that can modify the system like rm, mv, or install packages.

"""

print(f"--- Agent is executing command: {command} ---")

if not command:

return "Error: No command provided to execute."

try:

# Using shlex.split for security against shell injection

result = subprocess.run(

shlex.split(command),

capture_output=True,

text=True,

check=True,

timeout=60

)

return f"Command output:\n{result.stdout}"

except Exception as e:

return f"An error occurred: {str(e)}"

# --- Initialize the Agent ---

def create_linux_agent():

"""Creates and returns a LangChain agent configured with the shell tool."""

# Pull the ReAct prompt template

# ReAct (Reasoning and Acting) is a powerful way for agents to think step-by-step

prompt = hub.pull("hwchase17/react")

# Initialize the LLM

llm = ChatOpenAI(temperature=0, model="gpt-4-turbo-preview")

# Define the list of tools available to the agent

tools = [execute_shell_command]

# Create the agent by binding the LLM with the tools

agent = create_react_agent(llm, tools, prompt)

# Create the Agent Executor, which runs the agent's logic loop

agent_executor = AgentExecutor(agent=agent, tools=tools, verbose=True)

return agent_executor

if __name__ == "__main__":

linux_agent_executor = create_linux_agent()

# --- Give the Agent a Task ---

task = "What is the operating system, and what is the disk usage of the root filesystem?"

# The agent will now reason, choose the 'execute_shell_command' tool,

# run 'uname -a' and 'df -h /', and synthesize an answer.

response = linux_agent_executor.invoke({"input": task})

print("\n--- Final Answer ---")

print(response["output"])When you run this script, the verbose=True flag will show you the agent’s thought process. It will identify the two sub-tasks, execute uname -a, observe the output, then execute df -h /, observe that output, and finally combine the information into a coherent, human-readable answer. This demonstrates a leap beyond simple scripting, touching on areas of Linux DevOps and intelligent automation.

Advanced Agentic Workflows and Security Considerations

The real power of AI agents emerges when they handle complex, multi-step workflows that would traditionally require significant human expertise. Consider tasks related to Kubernetes Linux news or managing containerized applications with Docker or Podman.

Multi-Agent Systems for Complex Tasks

Frameworks like CrewAI and Microsoft’s Autogen allow you to create teams of specialized agents that collaborate to solve a problem. For a DevOps task, you might have:

- Planner Agent: Breaks down a high-level goal (e.g., “Deploy a new version of the web app”) into a sequence of steps.

- Code Agent: Writes the necessary Kubernetes manifest (

deployment.yaml) or Dockerfile. - Execution Agent: A heavily sandboxed agent that runs

kubectl apply -fordocker buildcommands. - Verification Agent: Runs commands like

kubectl get podsor sends a test HTTP request to confirm the deployment was successful.

This separation of concerns not only improves reliability but also enhances security by limiting the capabilities of each agent.

CRITICAL: The Security Imperative

Granting an AI the ability to execute arbitrary code on a Linux server is inherently dangerous. A single mistake or a cleverly crafted malicious prompt could lead to catastrophic data loss or a system compromise. This is the most important topic in Linux security news related to AI. Here are some non-negotiable best practices:

- Sandboxing: Never run an agent with root privileges or as a privileged user on a production system. The agent’s execution environment must be heavily restricted. Use technologies like:

- Linux Containers: Run the agent inside a minimal Docker or Podman container with no unnecessary permissions and a read-only root filesystem.

- systemd-nspawn: A powerful tool for creating lightweight container-like environments.

- Virtual Machines: For maximum isolation, run the agent inside a dedicated KVM/QEMU virtual machine.

- Principle of Least Privilege: The agent should only have access to the specific commands and files it needs to perform its task. Use

sudoersrules, file permissions, and security modules like SELinux or AppArmor to enforce strict boundaries. - Human-in-the-Loop (HITL): For any action that modifies the system (e.g., installing a package with

aptordnf, deleting a file withrm, or applying a firewall rule withnftables), the agent should be required to ask for human confirmation. The agent should propose the command, and a human operator must approve it before execution. - Strict Tool Definition: When defining tools for the agent, be as specific as possible. Instead of a generic

execute_shell_command, create tools likecheck_service_status(service_name: str)orget_disk_usage(path: str). This limits the agent’s “action space” and reduces the risk of misuse.

Here’s a conceptual code snippet illustrating a safer tool with a confirmation step.

@tool

def execute_dangerous_command(command: str) -> str:

"""

Executes a potentially dangerous command that modifies the system.

This tool will ALWAYS ask for human confirmation before running.

Example commands: 'sudo systemctl restart nginx', 'rm temp_file.txt'

"""

# List of keywords that signify a dangerous operation

DANGEROUS_KEYWORDS = ["sudo", "rm", "mv", "dd", "mkfs", "apt", "yum", "dnf", "pacman"]

is_dangerous = any(keyword in command.lower().split() for keyword in DANGEROUS_KEYWORDS)

if not is_dangerous:

return "Error: This command does not seem to require confirmation. Use a read-only tool instead."

print(f"\n!!! HUMAN CONFIRMATION REQUIRED !!!")

print(f"Agent wants to execute the following command: '{command}'")

try:

confirm = input("Do you approve this action? [y/N]: ")

if confirm.lower() != 'y':

return "Action was rejected by the user."

except EOFError:

# Handle non-interactive environments

return "Action rejected. No user input received."

print("--- User approved. Executing command. ---")

# The actual execution logic from the previous example would go here

# For demonstration, we'll just return a success message.

# return execute_linux_command(command)

return f"Successfully executed user-approved command: {command}"

# Agent's thought process would lead it to call this tool for a restart task.

# For example: execute_dangerous_command("sudo systemctl restart nginx")Conclusion: The Future of Linux Administration is Collaborative

The emergence of AI agents in the Linux cloud is not about replacing human administrators but augmenting them. These tools have the potential to act as tireless assistants, handling routine diagnostics, performing initial incident triage, and automating complex deployments across a wide range of distributions, from Fedora and openSUSE to the vast ecosystems of AWS Linux and Google Cloud Linux. They can dramatically reduce toil and allow DevOps engineers and SREs to focus on higher-level architectural challenges.

However, this powerful technology must be wielded with extreme caution. The focus for the immediate future will be on building robust safety rails, secure sandboxing environments, and reliable human-in-the-loop workflows. As the open-source community continues to innovate in this space, we can expect to see more sophisticated and secure agentic frameworks become a standard part of the modern Linux administration toolkit. The key takeaway is to start experimenting now in controlled, non-production environments. Understand the capabilities, but more importantly, understand the risks. The future of the Linux command line is about to get a lot more intelligent.