The System Administrator’s Guide to Linux Package Management: Avoiding the `sudo` Trap

Introduction: The Bedrock of a Stable Linux System

In the world of Linux, package managers are the unsung heroes. They are the sophisticated tools that handle the installation, configuration, updating, and removal of software, forming the bedrock of a stable and functional system. From the robust apt in Debian and Ubuntu to the powerful dnf in Fedora and the minimalist pacman in Arch Linux, these native tools are meticulously designed to manage the core operating system and its trusted applications. However, the landscape of software development has introduced a new class of package managers—language-specific and application-level tools like npm, pip, and Cargo. While incredibly powerful for developers, their misuse can lead to catastrophic system instability. Recent events in the open-source community have highlighted a critical, often overlooked principle: the danger of running third-party package managers with root privileges. This article delves into the fundamental distinctions between system and application package managers, explores the severe risks of privilege escalation, and provides a comprehensive guide to modern best practices, ensuring your Linux environment remains secure, stable, and predictable. This is essential reading for anyone from a Linux desktop enthusiast to a seasoned DevOps engineer managing fleets of servers.

The Great Divide: System vs. Application Package Management

Understanding the distinct roles of different package managers is the first step toward responsible system administration. Confusing their purposes is a common pitfall that can lead to broken dependencies, security vulnerabilities, and systems that are difficult to maintain or debug. At a high level, they operate in two separate domains: the global system scope and the local user/project scope.

System Package Managers: The Guardians of the OS

System package managers like apt, yum/dnf, pacman, and zypper are the official gatekeepers for your distribution. Their primary responsibilities include:

- Managing Core System Components: They handle the Linux kernel, system libraries (like glibc), desktop environments (GNOME, KDE Plasma), and essential system services managed by systemd.

- Ensuring Dependency Resolution: They maintain a complex, rigorously tested dependency tree. When you install a package like Nginx, your system package manager ensures all required libraries and tools are installed alongside it, preventing conflicts.

- Providing Security and Stability: Packages in official repositories (e.g., for Ubuntu, Debian, Red Hat, or Arch Linux) are vetted, tested, and signed by the distribution maintainers. This process provides a strong guarantee of stability and security.

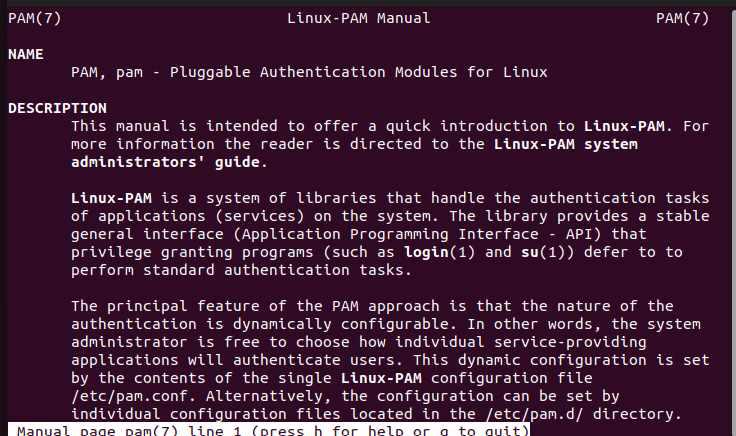

These managers rightly require root privileges (via sudo) because they modify critical, system-wide directories like /usr/bin, /lib, and /etc. This is their designated territory.

# Example: Installing the 'htop' utility on a Debian/Ubuntu system

# This command correctly uses sudo because apt manages the core system.

sudo apt update

sudo apt install htop

# Example: Installing development tools on a Fedora/RHEL system

# dnf also operates on the system level and requires root privileges.

sudo dnf groupinstall "Development Tools"Application Package Managers: The Developer’s Toolkit

In contrast, application-level or language-specific package managers are designed for a different purpose. Tools like npm (JavaScript), pip (Python), cargo (Rust), and gem (Ruby) manage libraries and dependencies for specific programming projects. Their key characteristics are:

- Project-Specific Scope: Their primary goal is to manage dependencies for a single application or workspace, not the entire operating system.

- Rapid Release Cycles: Registries like npmjs and PyPI contain tens of thousands of packages with rapid, unvetted updates, which is great for development agility but risky for system stability.

- User-Space Operation: They are designed to be run by a regular user, installing packages into a local project directory (e.g.,

node_modules) or the user’s home directory.

When you run npm install inside your project folder, it reads your package.json and downloads the required libraries into a local node_modules folder. This action requires no special permissions and has no impact on the wider system. The problem arises when developers attempt to use these tools for “global” installations with root privileges.

The Perils of Privilege: Why `sudo npm install -g` is a Recipe for Disaster

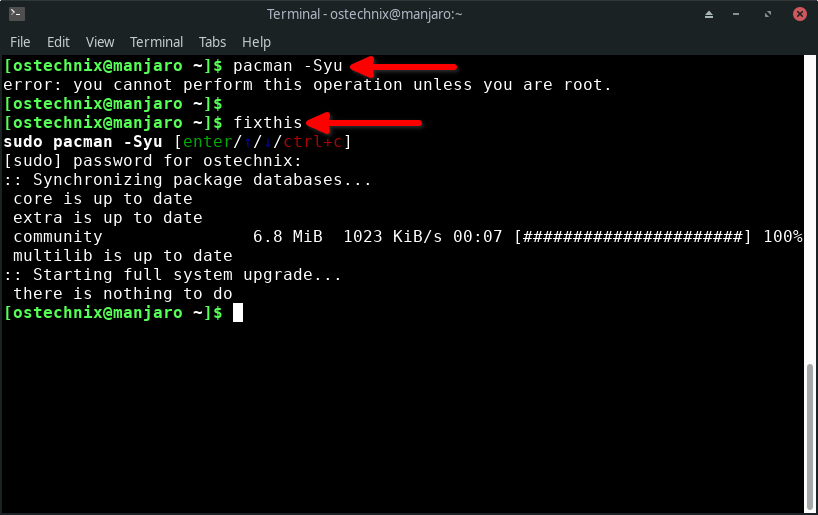

The command sudo npm install -g <package> is a notorious anti-pattern. It instructs a tool designed for user-space development to operate with the highest level of system privilege. This seemingly innocuous command can wreak havoc in several ways, a topic frequently discussed in recent Linux security news.

Filesystem Collisions and Permission Chaos

When run with sudo, npm will attempt to install packages into system directories like /usr/lib/node_modules and create symbolic links in /usr/bin/. This immediately creates a conflict. Your system package manager, be it apt or dnf, believes it has exclusive control over these directories. An npm package could inadvertently overwrite a critical system binary or library that shares the same name, leading to unpredictable behavior or a completely broken system. Furthermore, it creates files owned by the root user in places where user-level tools might expect to write, leading to a cascade of permission errors.

Arbitrary Code Execution and Security Risks

The most alarming risk is security. Package registries like npm and PyPI are vast and largely automated. Malicious actors can and do publish packages with compromised code. Most packages include pre-installation and post-installation scripts that are executed automatically. If you run the installation with sudo, these scripts are executed as the root user.

A malicious script could:

- Install a rootkit or backdoor.

- Modify system configuration files like

/etc/passwdor SSH settings. - Delete critical system data (

rm -rf /). - Exfiltrate sensitive information.

This turns a simple package installation into a game of Russian roulette with your system’s security. It completely bypasses the security vetting provided by your Linux distribution’s maintainers.

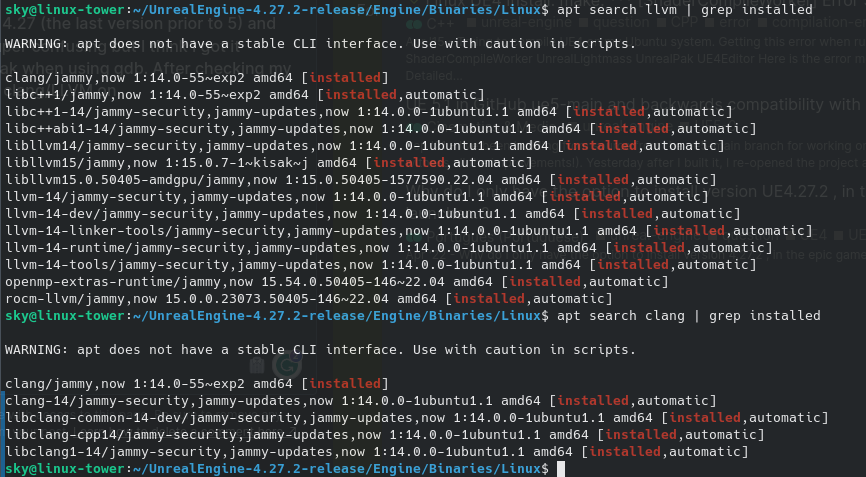

“Dependency Hell” on a System-Wide Scale

A core principle of good system administration is having a single source of truth for package management. When you mix apt and sudo npm, you create two competing managers fighting for control of the same filesystem. A Node.js package installed via npm might depend on a specific version of a library like OpenSSL, while a system application installed via apt depends on a different, security-patched version from the distribution. This conflict can break both the npm application and the system utility, leading to a nightmare scenario that is incredibly difficult to diagnose and fix, often forcing a complete system reinstall.

The Modern Solution: A Layered Approach with Isolation

The correct approach is not to abandon application package managers but to use them as intended: within isolated, user-controlled environments. Modern Linux DevOps and development workflows are built on this principle of isolation.

1. Language Version Managers (nvm, pyenv, sdkman)

Instead of installing development tools like Node.js or Python globally using your system’s package manager, use a dedicated version manager. These tools install toolchains into your user’s home directory, giving you complete control without needing sudo.

For Node.js development, Node Version Manager (nvm) is the standard. It allows you to install and switch between multiple Node.js versions on the fly.

# Install nvm (do NOT use sudo)

curl -o- https://raw.githubusercontent.com/nvm-sh/nvm/v0.39.7/install.sh | bash

# Source your shell configuration to load nvm

source ~/.bashrc

# Install the latest Long-Term Support (LTS) version of Node.js

nvm install --lts

# Set the LTS version as the default

nvm use --lts

# Now, install a global utility like 'pm2' WITHOUT sudo

# It will be installed safely in your user's home directory (~/.nvm/...)

npm install -g pm2

# Verify pm2 is in your user-level path

which pm2

# Output: /home/youruser/.nvm/versions/node/v20.12.2/bin/pm2Similarly, pyenv manages Python versions, and sdkman is excellent for Java, Kotlin, and other JVM languages. This approach completely decouples your development environment from the system’s core packages.

2. Project-Level Dependency Management (Virtual Environments)

For Python projects, virtual environments are non-negotiable. The built-in venv module creates a self-contained directory tree that holds a specific Python installation and its required packages.

# Create a new project directory

mkdir my-python-app && cd my-python-app

# Create a virtual environment named 'venv'

python3 -m venv venv

# Activate the virtual environment

# Your shell prompt will change to indicate activation.

source venv/bin/activate

# Now, install packages using pip. They will be installed ONLY

# inside the 'venv' directory, not globally.

pip install requests flask numpy

# See where the 'flask' executable is located

which flask

# Output: /home/youruser/my-python-app/venv/bin/flask

# When you're done, deactivate the environment

deactivateThis ensures that Project A’s dependencies never conflict with Project B’s, or more importantly, with the system’s Python packages. Node.js achieves this by default with its node_modules directory, and Rust does the same with its Cargo.toml file.

3. Containerization: The Ultimate Isolation (Docker, Podman)

For the highest level of isolation and reproducibility, containers are the gold standard. Tools like Docker and Podman allow you to package an application with all its dependencies—including specific versions of language runtimes and system libraries—into a single, portable image. This container runs in a completely isolated environment, sharing only the host system’s kernel.

This is a game-changer for Linux server news and cloud deployments, as it guarantees that an application will run identically on a developer’s laptop, a testing server, and in production on AWS, Google Cloud, or Azure.

# Dockerfile for a simple Node.js application

# Start from an official Node.js image

FROM node:20-slim

# Create a directory for the app inside the container

WORKDIR /usr/src/app

# Copy package.json and package-lock.json

COPY package*.json ./

# Install app dependencies inside the container

RUN npm install

# Copy the rest of the application source code

COPY . .

# Expose the port the app runs on

EXPOSE 3000

# Define the command to run the app

CMD [ "node", "server.js" ]With this `Dockerfile`, the host system doesn’t even need Node.js or npm installed. The entire development and runtime environment is self-contained, eliminating any possibility of conflict with the host OS.

Best Practices for Harmonious Package Management

To maintain a secure and stable Linux system, whether it’s a desktop running Pop!_OS or a server running AlmaLinux, adhere to these principles:

- Trust Your System Package Manager: For any software that needs to be integrated with the system (e.g., web servers, databases, system utilities), always use your distribution’s native package manager (

apt,dnf,pacman). - NEVER Use `sudo` with Application Managers: Make it a hard rule for yourself and your team. There is no valid modern use case for commands like

sudo pip installorsudo npm install -g. - Embrace Version Managers: Use tools like

nvm,pyenv, andrustupto manage your development toolchains in your user space. - Isolate Project Dependencies: Always use local project-level dependency management, such as Python’s

venv, Node’snode_modules, and Bundler for Ruby. - Containerize When Possible: For complex applications, especially in server and cloud environments, use Docker or Podman to achieve perfect isolation and reproducibility. This is a core tenet of modern Linux CI/CD news and practices.

- Use Universal Packages for Desktop Apps: For third-party desktop applications, consider sandboxed formats like Flatpak or Snap. They bundle dependencies and run in a more isolated manner than traditional packages, enhancing security.

Conclusion: The Right Tool for the Right Job

The Linux ecosystem’s strength lies in its layered, modular design. This philosophy must extend to how we manage software. System package managers are for the system; application package managers are for applications. Blurring this line by granting unnecessary root privileges to development tools is a direct path to instability and security breaches. By embracing modern isolation techniques—from version managers and virtual environments to full-fledged containerization—we can harness the power of the vast open-source software world without compromising the integrity of our operating systems. A disciplined, security-conscious approach to package management is not just a best practice; it is a fundamental requirement for any serious Linux user in today’s complex technological landscape.