My Battle-Tested Strategy for Securing MongoDB on Linux

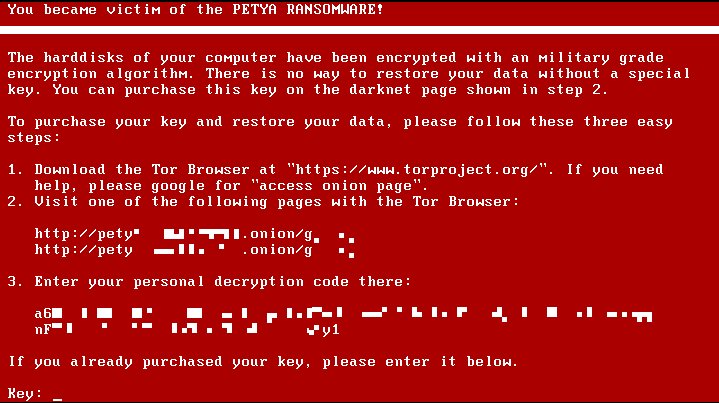

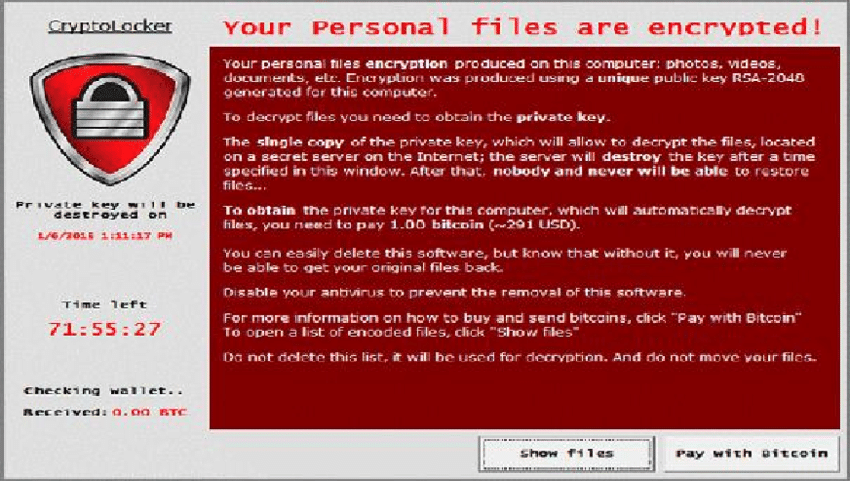

I still remember the sinking feeling in my gut the first time I saw a production database wiped clean. It wasn’t my server, thankfully, but I was the one called in to clean up the mess. The developers had spun up a MongoDB instance on a Debian box, left the default configuration, and went to lunch. By the time they came back, their data was gone, replaced by a ransom note demanding Bitcoin. That was years ago, but looking at the recent wave of attacks hitting thousands of databases this month, it seems not much has changed in how people deploy databases on Linux.

I see this constantly in Linux news feeds and security bulletins: admins assuming that “default” means “secure.” It doesn’t. With the recent spike in automated scripts scanning for open port 27017, I’m spending this week auditing every MongoDB Linux news alert and double-checking my own infrastructure. If you are running MongoDB on Ubuntu, CentOS, or Rocky Linux, you need to stop hoping for obscurity and start locking things down. Here is exactly how I secure my instances.

The Network Bind Trap

The single biggest mistake I see involves the bindIp setting. By default, many older packages or custom installs might bind to 0.0.0.0, which tells the server to listen on all interfaces. I never allow this. I always restrict MongoDB to listen only on localhost or a specific private VPN interface.

I edit the configuration file, usually located at /etc/mongod.conf on most Linux distributions like Fedora or AlmaLinux news sources often mention.

net:

port: 27017

bindIp: 127.0.0.1,10.8.0.5 # Only localhost and my private VPN IPAfter saving this, I restart the service. I always verify my work using ss or netstat. It’s a simple step, but it prevents the database from even acknowledging a connection attempt from the public internet.

sudo systemctl restart mongod

sudo ss -tulpn | grep 27017Enforcing Access Control

It baffles me that authentication isn’t enabled by default in some install methods. I treat Linux security news warnings about unauthorized access seriously. Before I even expose the database to my application, I create an administrative user. If you don’t do this, anyone who can connect to the port has full root access to your data.

I connect to the shell via mongosh and switch to the admin database. Here is the query logic I use to bootstrap the admin user:

use admin

db.createUser(

{

user: "sysadmin",

pwd: passwordPrompt(), // I never type passwords in plain text history

roles: [ { role: "userAdminAnyDatabase", db: "admin" }, "readWriteAnyDatabase" ]

}

)Once the user is created, I enable authorization in the configuration file. This is the step most people forget until they read about a breach in Linux server news.

security:

authorization: enabledFirewalling at the OS Level

Even with MongoDB configured correctly, I don’t trust the application layer alone. I use iptables news and tutorials as a reference, but I prefer using UFW on Ubuntu or firewalld on RHEL-based systems for simplicity. The goal is to whitelist only the application servers.

If my web server is on 192.168.1.50, I explicitly allow that IP and drop everything else. This is standard Linux administration news advice, but it bears repeating.

# Using UFW on Ubuntu/Debian

sudo ufw allow from 192.168.1.50 to any port 27017

sudo ufw deny 27017

sudo ufw enableFor those running Docker Linux news enthusiasts setups, I ensure that I’m not publishing the port globally in my docker-compose.yml. Mapping "27017:27017" exposes it to the world. I map it to localhost with "127.0.0.1:27017:27017" unless I have a very specific reason not to.

Practical Database Operations for Stability

Security isn’t just about hackers; it’s about data integrity. A crashed database is just as useless as a stolen one. I use schema validation to ensure that my application doesn’t insert garbage data. While MongoDB is “schemaless,” I find that defining rules prevents a lot of headaches later.

Here is how I define a collection with strict validation rules. Think of this as the CREATE TABLE equivalent in the Linux database news world.

db.createCollection("server_logs", {

validator: {

$jsonSchema: {

bsonType: "object",

required: [ "hostname", "severity", "timestamp" ],

properties: {

hostname: {

bsonType: "string",

description: "must be a string and is required"

},

severity: {

enum: [ "INFO", "WARN", "ERROR", "CRITICAL" ],

description: "can only be one of the enum values"

},

timestamp: {

bsonType: "date",

description: "must be a date"

}

}

}

}

})Next, I focus on performance. I’ve seen servers brought to their knees by unindexed queries. In Linux performance news, high CPU usage is often traced back to full collection scans. I create compound indexes to support my most frequent queries.

// Creating a compound index on hostname and timestamp

// -1 indicates descending order for the timestamp (newest first)

db.server_logs.createIndex( { hostname: 1, timestamp: -1 } )Finally, for critical operations where data consistency is non-negotiable—like financial transactions or inventory management—I use multi-document transactions. This feature has been stable for a while, but I still see developers avoiding it. If I’m updating an inventory count and logging a sale, either both happen, or neither happens.

// Start a session

const session = db.getMongo().startSession();

session.startTransaction();

try {

const inventory = session.getDatabase("store").collection("inventory");

const orders = session.getDatabase("store").collection("orders");

// Decrement inventory

inventory.updateOne(

{ sku: "LNX-USB-001" },

{ $inc: { qty: -1 } }

);

// Insert order record

orders.insertOne({

sku: "LNX-USB-001",

customer: "user_123",

date: new Date()

});

// Commit the transaction

session.commitTransaction();

print("Transaction committed successfully.");

} catch (error) {

// Abort on error

session.abortTransaction();

print("Transaction aborted due to error: " + error);

} finally {

session.endSession();

}Monitoring and Auditing

I don’t stop at configuration. I need to know what is happening inside the engine. I set up Linux monitoring news tools like Prometheus with the MongoDB exporter to track connection counts and operation latencies. If connection attempts spike, I want an alert immediately.

I also enable the system log to track authentication attempts. In the mongod.conf, I adjust the systemLog verbosity. This helps me in Linux forensics news scenarios if I ever need to trace back an intrusion attempt.

systemLog:

destination: file

path: /var/log/mongodb/mongod.log

logAppend: true

verbosity: 1For those managing fleets of servers, I recommend looking into automation tools discussed in Ansible news or Terraform Linux news. Hardening one server manually is fine; hardening fifty requires a playbook. I wrote an Ansible role specifically to enforce the bindIp and security.authorization settings across all my nodes, ensuring no new deployment slips through the cracks.

Why This Matters Right Now

The threat environment isn’t static. We aren’t just dealing with script kiddies anymore; we are dealing with automated ransomware-as-a-service platforms that can scan the entire IPv4 space in minutes. When I read Linux incident response news, the common thread is almost always a lack of basic hygiene—open ports, default passwords, or unpatched software.

I urge you to log into your servers today. Run a quick check. Are you listening on 0.0.0.0? Is auth enabled? It takes five minutes to check and could save you weeks of recovery time. Don’t be the next statistic in the Linux security news headlines.