Optimizing Linux Footprints: A Deep Dive into Fedora’s Proposal for Hardlink Deduplication

In the ever-evolving landscape of Linux distributions, the pursuit of efficiency is a constant driving force. From the kernel to the user space, developers are relentlessly seeking ways to reduce resource consumption, speed up operations, and streamline system administration. A fascinating new proposal emerging from the Fedora Project highlights this trend, aiming to tackle storage bloat by leveraging one of the oldest and most fundamental features of Unix-like filesystems: the hardlink. This initiative, a significant piece of recent Fedora news, proposes to automatically deduplicate identical files within the /usr directory during package installation, a move that could have far-reaching implications for cloud deployments, containerization, and general desktop usage.

This article provides a comprehensive technical exploration of this innovative approach. We will dissect the underlying technology of inodes and hardlinks, examine the specifics of the Fedora proposal, compare it to other deduplication methods like those found in Btrfs and ZFS, and discuss the practical consequences for system administrators and developers. This development is not just relevant to the Red Hat ecosystem but serves as a bellwether for trends that could influence Ubuntu news, Debian news, and the broader Linux open source community.

The Foundation: A Refresher on Inodes and Links

To fully grasp the elegance and the trade-offs of Fedora’s proposal, we must first revisit the core concepts of how Linux filesystems manage data. The magic happens at the inode level, a data structure that is fundamental to understanding file storage and a topic often covered in Linux kernel news.

Understanding the Inode

On a Unix-like filesystem such as ext4 or XFS, a file is not just a name with some data. The file’s name, located within a directory, is merely a human-readable label that points to an inode. The inode is the true heart of the file; it’s a metadata record stored on the disk that contains crucial information: the file’s permissions, owner, group, size, timestamps, and most importantly, pointers to the actual data blocks on the storage device. Every file and directory has a unique inode number on a given filesystem.

Hardlinks: One File, Many Names

A hardlink is a second directory entry that points to the exact same inode as another file. It is not a copy or a pointer to a filename; it is a direct link to the file’s underlying data and metadata. When you create a hardlink, you are essentially giving an existing file a new name in the same or a different directory (on the same filesystem). The inode maintains a “link count” or “reference count,” which tracks how many directory entries point to it. The actual data blocks on the disk are only freed when this link count drops to zero, meaning all hardlinks (including the original filename) have been deleted. This is a key principle in Linux filesystems news and administration.

Here is a practical demonstration of creating a hardlink and observing its properties.

# Create an original file

echo "This data is stored only once." > original_file.txt

# Display the file's inode number and details

# Note the inode number (first column) and the link count (third column, "1")

ls -li original_file.txt

# Create a hardlink to the original file

ln original_file.txt hardlinked_file.txt

# Display details for both files

# Notice they share the SAME inode number and the link count is now "2"

ls -li original_file.txt hardlinked_file.txt

# Modifying one "file" affects the other, as they are the same data

echo " Appended text." >> hardlinked_file.txt

cat original_file.txt

# Removing the original file does not delete the data

rm original_file.txt

echo "Original removed. Checking hardlink:"

cat hardlinked_file.txtSymbolic Links: A Different Beast

It’s crucial to distinguish hardlinks from symbolic links (softlinks), created with ln -s. A softlink is a special type of file that contains a path to another file or directory. It points to a filename, not an inode. If the original file is deleted or moved, the symbolic link breaks. Hardlinks are more robust in this regard but are limited to the same filesystem, whereas symbolic links can span across different filesystems.

Fedora’s Proposal: System-Wide Deduplication via RPM

The core of the Fedora proposal is to apply the hardlink concept systematically and automatically at the package management level. This is a significant development in Linux package managers news, directly impacting the behavior of DNF and RPM.

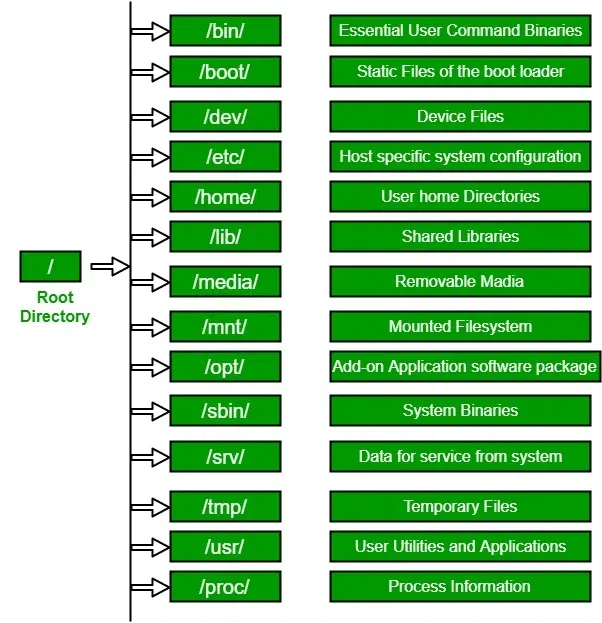

The Target: Why /usr?

The proposal specifically targets the /usr directory. This is a logical choice because /usr (“Unix System Resources”) contains the vast majority of the operating system’s shareable, read-only data. This includes binaries (/usr/bin), libraries (/usr/lib), documentation (/usr/share/doc), and license files (/usr/share/licenses). Across the thousands of packages installed on a typical Linux system, there is a surprising amount of duplication. Many packages ship with identical copies of license texts (e.g., GPL, MIT, Apache), icons, or even small helper scripts. Deduplicating these assets can lead to significant space savings.

The Proposed Mechanism

The plan involves integrating a post-transaction hook into the RPM/DNF process. After a package’s files are extracted, a tool would scan the newly installed files within /usr. For each file, it would calculate a cryptographic hash (like SHA-256) of its content. This hash would then be checked against an index of hashes for all other files already present in /usr.

If an identical hash is found, meaning an identical file already exists elsewhere, the newly installed file is removed and replaced with a hardlink to the existing one. If no match is found, the new file’s hash is added to the index for future comparisons. This process makes the deduplication an integral part of system updates and package installations, a key update for Linux administration news.

The logic can be illustrated with the following conceptual script:

#!/bin/bash

# --- Conceptual script illustrating the hardlinking logic ---

# This is for demonstration purposes only.

# A database file to store hashes and paths

HASH_DB="/var/lib/rpm-hardlink/usr_hashes.db"

# The newly installed file from an RPM package

NEW_FILE="$1"

# Ensure the new file is within /usr

if [[ ! "$NEW_FILE" == /usr/* ]]; then

exit 0

fi

# Calculate the hash of the new file's content

NEW_HASH=$(sha256sum "$NEW_FILE" | awk '{print $1}')

# Look up the hash in our database

EXISTING_PATH=$(grep "^${NEW_HASH}:" "$HASH_DB" | cut -d':' -f2-)

if [ -n "$EXISTING_PATH" ] && [ -f "$EXISTING_PATH" ]; then

# Found an identical file, get its inode

EXISTING_INODE=$(stat -c %i "$EXISTING_PATH")

NEW_INODE=$(stat -c %i "$NEW_FILE")

# Avoid linking a file to itself

if [ "$EXISTING_INODE" != "$NEW_INODE" ]; then

echo "Duplicate found for $NEW_FILE. Linking to $EXISTING_PATH"

# Temporarily move the new file

mv "$NEW_FILE" "${NEW_FILE}.tmp"

# Create the hardlink

ln "$EXISTING_PATH" "$NEW_FILE"

# Remove the temporary file

rm "${NEW_FILE}.tmp"

fi

else

# No duplicate found, add this new file to the database

echo "Indexing new file: $NEW_FILE"

echo "${NEW_HASH}:${NEW_FILE}" >> "$HASH_DB"

fiThe Expected Benefits

The primary benefit is a reduction in disk space usage. This is especially valuable in environments where storage is at a premium, such as in cloud virtual machines, Linux containers (Docker, Podman), and embedded systems. For a fleet of containers based on the same Fedora image, the savings multiply. Secondary benefits include potentially faster package installations (less data to write) and improved filesystem cache efficiency, as the kernel only needs to cache one copy of the data for all its hardlinks. This is important Linux performance news for anyone managing systems at scale.

Hardlinks vs. Filesystem-Level Deduplication: A Comparative Analysis

Fedora’s proposal is not the only way to achieve deduplication. Modern filesystems like Btrfs and ZFS offer this feature at a much lower level. Understanding the differences is key to appreciating the design choices being made.

The Btrfs and ZFS Approach

Filesystems like Btrfs provide offline, block-level deduplication. A userspace tool can scan the filesystem, identify identical data blocks (not just entire files), and merge them so that only one copy is stored. ZFS offers inline, real-time deduplication, checking every block as it’s written. This is more comprehensive but can come with a significant performance and memory overhead. This area of Btrfs news and ZFS news is always active, with continuous improvements being made.

A Tale of Two Philosophies

- Hardlink Method (Fedora):

- Pros: It is filesystem-agnostic, working seamlessly on the ubiquitous ext4 as well as XFS and Btrfs. The deduplication logic runs only during package transactions, imposing no continuous runtime overhead. It’s a pragmatic, targeted solution.

- Cons: It only deduplicates whole, identical files managed by the package manager. It cannot deduplicate parts of files or user-generated data. The biggest challenge is user and tool awareness; editing a hardlinked file will change all its linked “copies,” which can be unexpected. It also requires careful handling of permissions and Linux SELinux contexts.

- Filesystem Method (Btrfs/ZFS):

- Pros: Far more powerful, as it works at the block level. It can find and merge identical chunks of data across all files on the system, not just those in

/usr. The process is entirely transparent to applications and users. - Cons: It is filesystem-specific, requiring the user to have chosen Btrfs or ZFS from the start. Inline deduplication (ZFS) can be resource-intensive, while offline deduplication (Btrfs) requires periodic manual runs.

- Pros: Far more powerful, as it works at the block level. It can find and merge identical chunks of data across all files on the system, not just those in

The following Python script demonstrates the core task of finding duplicate files, which is what the proposed RPM tool would need to do efficiently.

import os

import hashlib

from collections import defaultdict

def find_duplicate_files(root_directory):

"""

Finds and groups duplicate files in a directory based on SHA256 hash.

Returns a dictionary where keys are hashes and values are lists of file paths.

"""

hashes = defaultdict(list)

print(f"Scanning '{root_directory}' for duplicate files...")

for dirpath, _, filenames in os.walk(root_directory):

for filename in filenames:

filepath = os.path.join(dirpath, filename)

# Ensure we only process regular files and not symlinks

if os.path.isfile(filepath) and not os.path.islink(filepath):

try:

with open(filepath, 'rb') as f:

# Read in chunks to handle large files efficiently

hasher = hashlib.sha256()

while chunk := f.read(8192):

hasher.update(chunk)

file_hash = hasher.hexdigest()

hashes[file_hash].append(filepath)

except (IOError, OSError) as e:

print(f"Warning: Could not read {filepath}: {e}")

continue

# Filter the dictionary to return only entries with more than one file path

return {hash_val: paths for hash_val, paths in hashes.items() if len(paths) > 1}

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Use a safe, local directory for testing.

# Scanning a large system directory like /usr can be slow and require permissions.

# Example: search_path = "/usr/share/doc"

search_path = "./test_data" # Create this directory and populate with some duplicate files to test

if not os.path.isdir(search_path):

print(f"Creating a test directory: {search_path}")

os.makedirs(search_path)

with open(os.path.join(search_path, "file1.txt"), "w") as f: f.write("This is a test.")

with open(os.path.join(search_path, "file2.txt"), "w") as f: f.write("This is a test.")

with open(os.path.join(search_path, "file3.txt"), "w") as f: f.write("This is different.")

duplicates = find_duplicate_files(search_path)

if duplicates:

print("\nFound the following duplicate files:")

for file_hash, paths in duplicates.items():

print(f"\nHash: {file_hash} (Size: {os.path.getsize(paths[0])} bytes)")

for path in paths:

print(f" -> {path}")

else:

print("No duplicate files were found.")Living in a Hardlinked World: Best Practices and Considerations

If this change is implemented, system administrators and developers will need to adapt their workflows and tools. While the change is designed to be largely transparent, awareness is key to avoiding confusion.

System Administration Perspective

A primary consideration is accurately monitoring disk usage. Standard tools like du -sh /usr will report the logical size, counting each hardlink as a full file, which can be misleading. To see the actual disk space used, you would need to use tools that account for shared blocks, or simply compare the output of df before and after major updates. Backup strategies are also critical. Modern backup tools relevant to Linux backup news, such as Borgbackup and Restic, are content-aware and deduplicate data on their own, making them largely unaffected. However, for traditional tools like tar and rsync, using the correct flags (e.g., --hard-links) is essential to preserve the linking structure and avoid storing redundant data in the backup.

To troubleshoot or simply explore the hardlink structure, an administrator can use the find command to locate all names pointing to a specific inode.

# 1. Find the inode number of a file you suspect is duplicated

# For example, a common license file

TARGET_FILE="/usr/share/licenses/bash/COPYING"

INODE_NUM=$(stat -c %i "$TARGET_FILE")

echo "Inode for ${TARGET_FILE} is ${INODE_NUM}"

# 2. Search the entire /usr directory for files with the same inode number

# The -xdev flag prevents find from crossing into other filesystems

echo "Searching for all hardlinks with inode ${INODE_NUM}..."

find /usr -xdev -inum ${INODE_NUM} -printFor Developers and Packagers

For those creating RPM packages, this change is mostly transparent. The best practice remains the same: package efficiently and avoid shipping unnecessary or duplicated assets. This initiative reinforces the importance of relying on shared system libraries and assets rather than bundling private copies. This aligns with broader trends in Linux development news and best practices for creating lean software distributions.

Conclusion: A Pragmatic Step Forward

Fedora’s proposal to use hardlinks for deduplicating /usr is a clever and pragmatic approach to an old problem. It represents a classic engineering trade-off, choosing a simple, filesystem-agnostic solution over a more powerful but complex and resource-intensive one. By integrating this logic directly into the package manager, Fedora aims to provide tangible storage savings out-of-the-box, benefiting everyone from cloud architects managing thousands of containers to desktop users on storage-constrained laptops.

This development is a prime example of the continuous innovation happening within the Linux open source ecosystem. While it may require a slight adjustment in thinking for system administrators, the potential benefits in efficiency and resource optimization are substantial. As this feature is tested and potentially rolled out, it will be fascinating to see the real-world metrics on space savings and whether other major distributions in the Arch Linux news or Debian worlds will consider similar strategies. It is a testament to the fact that even in 2024, there are still new and creative ways to apply the foundational principles of Unix to solve modern computing challenges.