Mastering Nginx Load Balancing in Modern Linux & Kubernetes Environments

The Evolution of Load Balancing: Why Nginx Still Dominates in a Cloud-Native World

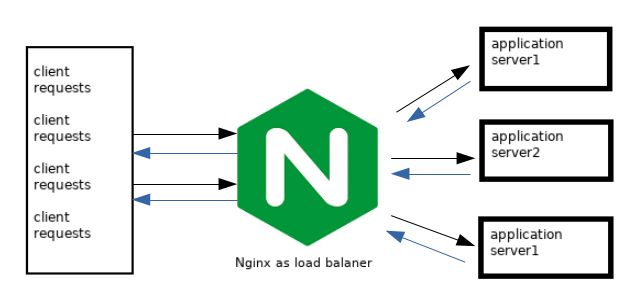

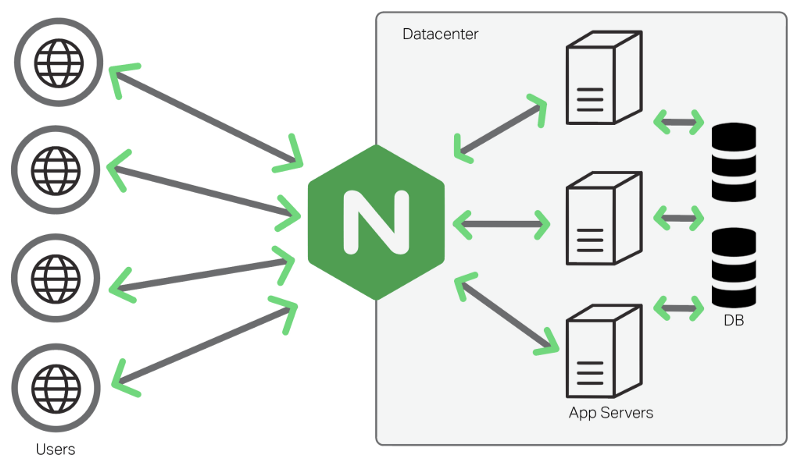

In the dynamic landscape of modern IT infrastructure, Nginx has remained a cornerstone technology for over two decades. Initially celebrated for its high-performance, event-driven architecture that solved the C10k problem, its role has evolved far beyond that of a simple web server. Today, Nginx is a critical component in complex, distributed systems, acting as a powerful reverse proxy, cache, and, most importantly, a sophisticated load balancer. As organizations increasingly adopt microservices and container orchestration platforms like Kubernetes, the need for intelligent traffic management has never been greater. This is where the latest developments in Nginx load balancing news become crucial for DevOps professionals, system administrators, and developers alike.

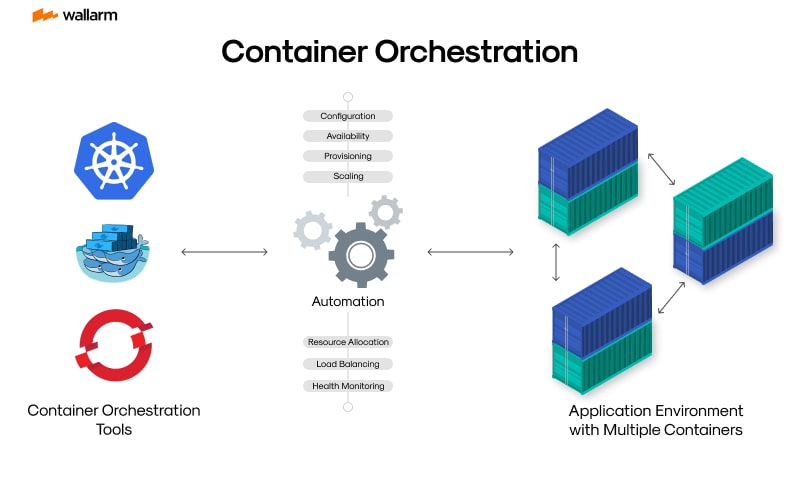

The shift towards containerization, heavily featured in recent Kubernetes Linux news and Docker Linux news, has fundamentally changed how applications are deployed and scaled. In this paradigm, ephemeral containers are spun up and down in response to demand, making static IP-based configurations obsolete. Nginx has adapted brilliantly to this new reality, particularly through its implementation as an Ingress Controller for Kubernetes. This allows it to dynamically route external traffic to the correct services within a cluster, providing a robust and flexible entry point. Whether you’re managing infrastructure on-premise with distributions covered in Red Hat news or Ubuntu news, or deploying to the cloud, Nginx provides a unified and performant solution for traffic management.

Core Concepts: The Building Blocks of Nginx Load Balancing

Before diving into containerized environments, it’s essential to understand the fundamental principles of Nginx load balancing. The magic happens within the Nginx configuration file, typically located at /etc/nginx/nginx.conf or in the /etc/nginx/conf.d/ directory on most Linux systems. The two primary directives you’ll work with are http, upstream, and server.

The upstream block is where you define a pool of backend servers that Nginx will distribute traffic to. This is a logical grouping of your application servers. The server block then uses the proxy_pass directive to forward requests to the defined upstream group.

Load Balancing Algorithms

Nginx offers several built-in methods for distributing requests among the servers in an upstream group:

- Round Robin: This is the default method. Requests are distributed evenly across the list of servers in sequential order. It’s simple and effective for stateless applications where servers are of similar capacity.

- Least Connections (

least_conn): Nginx sends the next request to the server with the fewest active connections. This is particularly useful for applications with long-lived connections, ensuring that no single server becomes a bottleneck. - IP Hash (

ip_hash): The server is determined based on a hash of the client’s IP address. This method ensures that requests from a specific client will always be directed to the same server, which is essential for maintaining session persistence (sticky sessions) in applications that require it.

A Practical Example: Basic Round-Robin Configuration

Here is a classic example of a simple load balancing setup. This configuration defines an upstream group named backend_app with three application servers. The main server block listens on port 80 and proxies all requests to this group using the default round-robin algorithm. This is a foundational skill for anyone following Linux administration news or aiming for RHCSA news certification.

# Define a pool of backend application servers

upstream backend_app {

# Default is round-robin

server app1.example.com:8080;

server app2.example.com:8080;

server app3.example.com:8080;

}

# The main server configuration that acts as the load balancer

server {

listen 80;

server_name www.example.com;

location / {

# Forward requests to the upstream group

proxy_pass http://backend_app;

# Set headers to pass client information to the backend

proxy_set_header Host $host;

proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-For $proxy_add_x_forwarded_for;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-Proto $scheme;

}

}Nginx in the Kubernetes Era: The Ingress Controller

While the traditional upstream configuration is perfect for static environments, modern Linux DevOps news is dominated by dynamic, orchestrated systems like Kubernetes and Red Hat OpenShift. In this world, services are ephemeral, and their IP addresses change frequently. Manually updating an Nginx configuration file is not feasible. This is the problem the Nginx Ingress Controller solves.

An Ingress Controller is a specialized load balancer for Kubernetes. It watches the Kubernetes API for Ingress resources, which are objects that define rules for routing external HTTP/S traffic to internal services. When an Ingress resource is created or updated, the Nginx Ingress Controller automatically reconfigures itself to implement those rules, providing a seamless bridge between the outside world and your cluster.

Implementing an Ingress Resource

Deploying an application behind an Nginx Ingress Controller involves creating a standard Kubernetes Deployment and Service, and then exposing that Service via an Ingress resource. The following YAML manifest defines an Ingress resource that routes traffic for myapp.example.com to a service named my-app-service on port 80. This is a daily task for engineers working with technologies covered in Google Cloud Linux news or AWS Linux news.

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: my-app-ingress

annotations:

nginx.ingress.kubernetes.io/rewrite-target: /

spec:

rules:

- host: "myapp.example.com"

http:

paths:

- path: /

pathType: Prefix

backend:

service:

name: my-app-service

port:

number: 80

Once you apply this manifest to your cluster, the Nginx Ingress Controller detects it and generates the necessary Nginx configuration to handle the routing. This level of automation is a core principle discussed in Linux automation news and is essential for effective CI/CD pipelines, often managed with tools like those featured in GitLab CI news.

Advanced Techniques and Configurations

Basic load balancing is just the beginning. Nginx provides a wealth of advanced features that allow for fine-grained traffic control, improved reliability, and enhanced security. These techniques are vital for building resilient, production-grade systems.

Passive Health Checks

You never want to send traffic to an unhealthy or unresponsive backend server. Nginx’s open-source version provides passive health checks. By using parameters like proxy_next_upstream, you can configure Nginx to mark a server as “failed” for a period if it returns an error or times out. This prevents users from being directed to a broken instance. NGINX Plus, the commercial version, offers more sophisticated active health checks that proactively probe backend servers.

upstream backend_app {

server app1.example.com:8080;

server app2.example.com:8080;

server app3.example.com:8080;

}

server {

listen 80;

server_name www.example.com;

location / {

proxy_pass http://backend_app;

# If a server returns an error or times out, try the next one

# 'fail_timeout' specifies how long to consider the server down

proxy_next_upstream error timeout http_502 http_503 http_504;

proxy_connect_timeout 2s;

# ... other proxy headers

}

}

SSL/TLS Termination

Encrypting traffic is non-negotiable, a constant theme in Linux security news. Nginx can act as an SSL/TLS termination point, decrypting incoming HTTPS traffic and forwarding it as unencrypted HTTP to your backend services. This offloads the computational overhead of encryption from your application servers, simplifying their configuration and improving performance. It also centralizes certificate management, a major administrative benefit.

server {

listen 443 ssl http2;

server_name www.example.com;

# SSL Certificate and Key paths

ssl_certificate /etc/ssl/certs/example.com.crt;

ssl_certificate_key /etc/ssl/private/example.com.key;

# Modern TLS settings

ssl_protocols TLSv1.2 TLSv1.3;

ssl_ciphers 'TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256:TLS_AES_256_GCM_SHA384';

ssl_prefer_server_ciphers off;

location / {

proxy_pass http://backend_app;

# ... proxy headers

}

}

Best Practices for Monitoring and Performance

Deploying a load balancer is not a “set it and forget it” task. Continuous monitoring and performance tuning are essential for maintaining a healthy and responsive application. This is a core tenet of modern Linux observability news.

Monitoring with Prometheus and Grafana

The combination of Prometheus for metrics collection and Grafana for visualization has become the de facto standard for monitoring cloud-native systems. The community provides a popular nginx-prometheus-exporter which scrapes metrics from Nginx’s stub_status module and exposes them in a format Prometheus can understand. Key metrics to watch include:

- Active connections: The current number of active client connections.

- Requests per second: The rate of incoming requests.

- Upstream response time: The time it takes for backend servers to respond.

- HTTP status codes: Monitoring the rate of 4xx and 5xx errors is critical for identifying application or infrastructure issues.

Here’s a sample Prometheus scrape configuration to collect metrics from the exporter. This configuration is a common sight in environments discussed in Linux monitoring news.

# prometheus.yml

scrape_configs:

- job_name: 'nginx'

static_configs:

- targets: ['nginx-exporter-hostname:9113']

Performance Tuning

While Nginx is fast out of the box, tuning it for your specific workload can yield significant performance gains. Key directives to consider in your nginx.conf include:

worker_processes: Typically set to the number of available CPU cores (orauto) to maximize parallel processing.worker_connections: Defines the maximum number of simultaneous connections that can be opened by a worker process.keepalive_timeout: Using persistent keepalive connections reduces the overhead of establishing new TCP connections for each request.

These settings, combined with a modern Linux kernel as highlighted in Linux kernel news, can help you handle massive amounts of traffic efficiently. For those running on enterprise distributions like those from the SUSE Linux news or Oracle Linux news circles, vendor-specific tuning guides are also available.

Conclusion: The Future of Nginx in a Linux-Powered World

Nginx’s journey from a high-performance web server to the intelligent traffic-routing brain of modern cloud-native applications is a testament to its powerful design and the vibrant open-source community behind it. Its role as a load balancer has become more critical than ever, seamlessly bridging the gap between external users and dynamic, containerized backends running on Linux.

By mastering its core load balancing concepts, embracing its role as a Kubernetes Ingress Controller, and implementing advanced techniques for health checking and security, you can build highly available, scalable, and resilient systems. As the worlds of Linux server news and container orchestration continue to merge, Nginx remains a foundational skill and an indispensable tool for any modern technologist. The next step is to explore its capabilities further, experiment with different configurations in your own environment, and stay current with the ever-evolving landscape of Nginx load balancing news.