Snap Packages Unpacked: Navigating the Controversy and Control in Linux App Distribution

The Universal Package Conundrum: A Deep Dive into Snap

In the diverse and often fragmented world of Linux distributions, package management has long been a defining characteristic and a source of complexity. The traditional model of distribution-specific formats like .deb for Debian/Ubuntu systems and .rpm for Fedora/Red Hat systems created a high barrier for developers wanting to distribute their software broadly. In response, a new generation of universal package formats emerged, promising to bundle applications with all their dependencies, allowing them to run consistently across any Linux distribution. Among these, Snap packages, developed by Canonical (the company behind Ubuntu), have become one of the most prominent and controversial solutions.

Recent developments in the community, such as the decision by distributions like Linux Mint to disable Snap support by default, have brought the debate surrounding this technology to the forefront. This isn’t just a technical squabble; it’s a conversation about the core philosophies of open source, user control, and the future of software distribution on the Linux desktop and server. This article provides a comprehensive technical exploration of the Snap ecosystem, the reasons behind the controversy, and practical guidance for users on how to manage, control, or even re-enable Snaps on their systems. We’ll explore the architecture, the command-line tools, and the real-world implications of choosing this modern packaging format.

Core Concepts: Deconstructing the Snap Architecture

To understand the debate surrounding Snaps, it’s essential to first grasp the technical components that make up the ecosystem. A Snap is more than just a package; it’s a system involving a background service, a command-line interface, and a centralized repository, all working in concert.

The Key Components of the Snap Ecosystem

The Snap framework is built on several key pillars that differentiate it from traditional package managers like apt or dnf.

- snapd: This is the heart of the system.

snapdis a background daemon (a system service) that runs with root privileges. It handles the mounting of snap packages, manages the security sandboxing, controls background updates, and provides the API that other tools use to interact with the system. Its ever-present nature is a key design choice that enables features like automatic updates but is also a source of criticism regarding system resource usage and control. - The Snap Package (

.snap): This is a single, compressed file containing the application executable, its libraries, and all other dependencies. It’s built on the SquashFS read-only filesystem. When a snap is “installed,” its filesystem is mounted into the system, making the application available to the user. This bundling is what ensures an application runs the same way everywhere, regardless of the host system’s libraries. - The Snap Store: Unlike the federated nature of Flatpak’s Flathub or the decentralized model of AppImage, the Snap ecosystem relies on a single, centralized, proprietary backend controlled by Canonical. All snap installations, by default, point to this store. This ensures a single source of truth but raises concerns in the open-source community about vendor lock-in and a single point of failure.

- Channels: Snaps offer a powerful channel system that allows developers to publish multiple versions of their application simultaneously. Users can choose to track a specific channel, such as

stable,candidate,beta, oredge, giving them control over how bleeding-edge they want their software to be.

Practical Snap Commands

Interacting with the Snap ecosystem is primarily done through the snap command-line tool. Here are some of the most fundamental commands for managing snap packages.

# Search for a package in the Snap Store

snap find vlc

# Install a package (e.g., VLC media player) from the stable channel

sudo snap install vlc

# List all installed snap packages

snap list

# Get detailed information about a specific snap

snap info vlc

# Remove a snap package

sudo snap remove vlc

# Manually refresh all snaps (check for updates)

sudo snap refreshThese commands provide a straightforward interface for managing applications, but the real power and complexity lie in the underlying snapd service that executes these requests.

The Technical and Philosophical Divide: Why Some Distros Are Opting Out

The decision by Linux Mint and other community members to move away from Snaps isn’t arbitrary. It stems from a combination of technical performance issues and deep-seated philosophical disagreements with Canonical’s approach.

Performance and Integration Issues

One of the most common user complaints about Snaps is performance, particularly application startup time. Because a snap is a compressed SquashFS image, the snapd service must mount this filesystem and set up a security sandbox every time the application is launched for the first time after a boot. This can introduce a noticeable delay compared to a natively installed application. While subsequent launches are faster due to caching, the initial lag can be frustrating on a desktop system. Furthermore, because snaps are sandboxed and self-contained, they sometimes struggle with system integration, leading to issues with GTK/Qt theming, font rendering, and access to files outside the user’s home directory.

Centralization and Lack of Control

For many in the Linux open source news community, the biggest issue is the proprietary, closed-source nature of the Snap Store backend. This centralization goes against the grain of Linux’s traditionally open and federated ethos. Critics argue it gives Canonical too much control over software distribution. This concern was exacerbated by a controversial decision in Ubuntu where running sudo apt install chromium-browser would, without explicit warning, install the Snap version of Chromium instead of a traditional Debian package. This “bait and switch” was seen by many, including the Linux Mint news team, as an overreach that undermined user choice and the transparency of the apt package manager.

Forced Automatic Updates

By default, snapd checks for updates multiple times a day and applies them automatically in the background. While this is beneficial for security, it removes granular control from the user or system administrator. A server running a critical application could be updated unexpectedly, potentially introducing breaking changes. You can check the status of the snapd service, which manages these updates, using systemd.

# Check the status of the snapd service

systemctl status snapd.service

# You can also check the socket and timer units

systemctl status snapd.socket

systemctl list-timers | grep snapdThis forced update mechanism is a significant departure from how traditional package managers like apt or dnf operate, where updates are almost always a user-initiated action.

Taking Back Control: Managing and Re-enabling Snaps

Despite the controversy, Snaps provide access to a vast library of applications that might not be available in a distribution’s native repositories. For users of distributions like Linux Mint who still wish to use Snaps, or for users on any distro who want more control, it’s entirely possible to manage the system to your liking.

How to Enable Snap Support on Linux Mint

Linux Mint 20 and newer versions include a file that explicitly blocks the installation of snapd via apt. Re-enabling support is a matter of removing this block and then proceeding with the standard installation.

Here is a step-by-step guide to get Snap working on a fresh Linux Mint installation:

- Remove the blocking preference file: The file

/etc/apt/preferences.d/nosnap.prefpreventsaptfrom finding thesnapdpackage. You must remove it first. - Update the package list: After removing the file, refresh your

aptcache to recognize the change. - Install snapd: With the block removed, you can now install the

snapdpackage as you would on Ubuntu.

The following commands will accomplish this entire process:

# Step 1: Remove the preference file that blocks snapd installation

sudo rm /etc/apt/preferences.d/nosnap.pref

# Step 2: Refresh your APT package lists

sudo apt update

# Step 3: Install the snapd daemon

sudo apt install snapd

# Step 4 (Optional but recommended): Install core snap to ensure base is set up

sudo snap install coreAfter completing these steps, you will have a fully functional Snap environment on Linux Mint, capable of installing any application from the Snap Store.

Controlling Snap Updates

If you dislike the forced automatic updates, you have a few options to regain control. You can’t disable them completely, but you can manage their timing and temporarily pause them.

# Defer updates for a specific package (e.g., firefox) indefinitely

# Note: This is a temporary hold. It will be updated on the next global refresh.

# A more robust solution is managing the refresh timer.

sudo snap refresh --hold firefox

# To see when the next automatic refresh is scheduled

snap refresh --time

# Set the refresh to occur only on the last Friday of the month between 1am and 3am

sudo snap set system refresh.timer=fri5,01:00-03:00

# Revert to the default timer (4 times per day)

sudo snap set system refresh.timer=By using the refresh.timer system key, you can schedule updates for a time that is convenient for you, such as overnight or on weekends, preventing interruptions during critical work hours.

Best Practices, Alternatives, and the Future of Linux Packaging

The decision to use Snaps, Flatpaks, AppImages, or traditional packages is not always mutually exclusive. A pragmatic approach often yields the best results for the end-user.

When to Consider Using Snaps

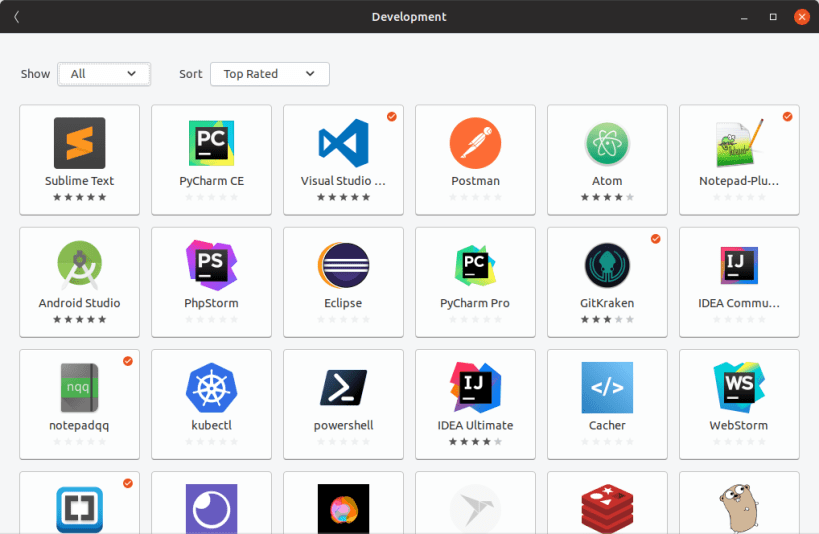

- Proprietary Software: For applications like Spotify, Slack, or Visual Studio Code, the Snap package is often the officially supported method of installation provided directly by the vendor.

- Server Applications: Snaps are excellent for self-contained server applications like Nextcloud or the Certbot client for Let’s Encrypt SSL certificates. The automatic updates and bundled dependencies simplify server administration and enhance security.

- Latest Software Versions: If you need the absolute latest version of a tool or application (e.g., a specific version of Go or Node.js for development), Snaps often provide it faster than distribution repositories.

Exploring the Alternatives: Flatpak and AppImage

The main competitor to Snap in the universal package space is Flatpak. Popularized by Fedora and the GNOME project, Flatpak is a fully open-source solution with a strong focus on desktop application sandboxing. Its primary repository, Flathub, is community-managed, and anyone can set up their own Flatpak remote. This federated model is philosophically more aligned with many in the Linux community. For users looking for an alternative, Flatpak is an excellent choice and is well-integrated into many desktop environments.

# Example of installing VLC using Flatpak (assuming Flatpak is installed)

# Add the Flathub repository if you haven't already

flatpak remote-add --if-not-exists flathub https://flathub.org/repo/flathub.flatpakrepo

# Install VLC from Flathub

flatpak install flathub org.videolan.VLC

# Run the Flatpak application

flatpak run org.videolan.VLCAppImage offers a third way. It follows a “one app, one file” philosophy. An AppImage is a single executable file that you can download, make executable, and run without any installation or background daemon. This makes it incredibly portable and simple to use, though it lacks the centralized update and management features of Snap or Flatpak.

Conclusion: A Matter of Informed Choice

The world of Snap packages news reflects a larger trend in the Linux ecosystem: a push-and-pull between user-centric control and developer-centric convenience. Snaps offer a powerful solution to the age-old problem of software distribution on Linux, providing developers with a simple way to package and ship up-to-date, secure applications directly to users. However, this convenience comes with trade-offs in performance, system integration, and, most importantly, control, due to its centralized and opinionated architecture.

The actions of distributions like Linux Mint are not a rejection of progress but a defense of user choice and the open, decentralized principles that have long defined the Linux community. For the end-user, the current landscape offers more choice than ever. By understanding the technical underpinnings of Snaps, the philosophical debates surrounding them, and the robust alternatives like Flatpak and AppImage, you are empowered to make an informed decision. You can choose to embrace the Snap ecosystem, re-enabling it where necessary, or opt for other solutions that may better align with your performance needs and personal philosophy. Ultimately, the power to shape your Linux experience remains exactly where it should be: in your hands.