Unlocking Nested Virtualization Performance: A Deep Dive into KVM Enhancements for Intel VMX

Introduction to the Next Leap in Linux Virtualization

The Linux kernel continues to be a hotbed of innovation, and its Kernel-based Virtual Machine (KVM) is no exception. As a core component of the modern cloud and data center, KVM’s performance and capabilities directly impact everything from massive public clouds to local development environments. One of the most technically demanding and powerful features of KVM is nested virtualization—the ability to run a hypervisor inside a virtual machine. This technology is critical for cloud providers offering bare-metal-like instances, complex CI/CD pipelines, and advanced security research. However, nested virtualization has historically come with a significant performance penalty due to the overhead of managing multiple layers of virtualization.

Recent developments in the Linux kernel are set to dramatically change this landscape, particularly for systems running on Intel processors with VMX (Virtual Machine Extensions). A series of sophisticated patches are introducing a more “enlightened” approach to handling nested guest operations, drastically reducing the number of costly transitions between the guest hypervisor and the host hypervisor. This article provides a comprehensive technical deep dive into these KVM news-worthy enhancements. We’ll explore the fundamentals of nested virtualization, dissect the performance bottlenecks, understand the mechanics of the new optimizations, and provide practical examples and best practices for system administrators and DevOps engineers working with distributions like Ubuntu, Fedora, Debian, and Red Hat Enterprise Linux.

Section 1: Core Concepts of KVM and Nested Virtualization

To appreciate the significance of these new KVM enhancements, it’s essential to first understand the foundational concepts of how KVM handles virtualization, especially in a nested context. This is crucial for anyone following Linux virtualization news and managing environments on platforms from Proxmox to Google Cloud Linux.

What is KVM?

KVM (Kernel-based Virtual Machine) is a Type-1 hypervisor integrated directly into the Linux kernel. It turns the kernel itself into a hypervisor, allowing it to manage and run virtual machines. KVM leverages hardware virtualization extensions built into modern processors, such as Intel VT-x and AMD-V. User-space tools like QEMU are used to emulate hardware peripherals and manage the VM lifecycle, while KVM handles the CPU and memory virtualization at the kernel level. This architecture provides near-native performance and is the backbone of many open-source virtualization platforms.

The Architecture of Nested Virtualization

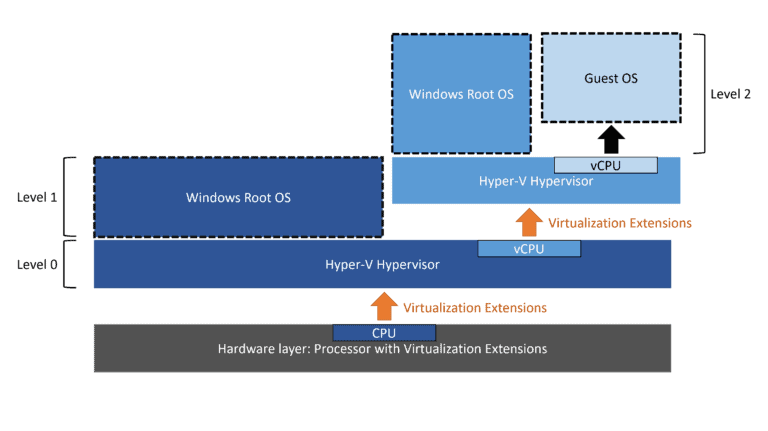

Nested virtualization introduces layers of hypervisors. The physical machine runs the primary hypervisor, referred to as L0. This L0 hypervisor runs a guest virtual machine (L1), which itself is configured to act as a hypervisor. This L1 hypervisor can then run its own guest VMs (L2).

- L0: The host hypervisor running directly on the physical hardware (e.g., a server running Debian with the latest Linux kernel).

- L1: The first-level guest VM, which is also a hypervisor (e.g., a VM running CentOS to host other containers or VMs).

- L2: The nested guest VM running inside the L1 hypervisor (e.g., a Docker container or a lightweight Alpine Linux VM for testing).

On Intel systems, this is made possible by the VMX instruction set. Before you can even begin, you must verify that your L0 host supports and has enabled nested virtualization. You can check this with a simple command.

# Check if nested virtualization is enabled for Intel processors

cat /sys/module/kvm_intel/parameters/nested

# The output should be 'Y' or '1'. If it is 'N', you may need to enable it.

# To enable it temporarily (until reboot):

sudo modprobe -r kvm_intel

sudo modprobe kvm_intel nested=1

# To enable it permanently, create a modprobe configuration file:

echo "options kvm_intel nested=1" | sudo tee /etc/modprobe.d/kvm-nested.confThis simple check is a critical first step for any administrator, whether on Arch Linux, SUSE Linux, or any other modern distribution, looking to leverage nested virtualization.

Section 2: The Performance Challenge: VM Exits and Shadow Structures

The primary performance bottleneck in nested virtualization is the “VM Exit.” A VM Exit is a transition from a guest VM back to the hypervisor, which needs to handle a privileged operation the guest cannot perform directly. In a nested setup, this problem is compounded, leading to a “double exit.”

The Double VM Exit Problem

When an L2 guest performs a privileged operation, it triggers a VM Exit to its hypervisor, L1. However, since L1 is itself a virtual machine, it cannot directly handle many of these hardware-level operations. This forces L1 to trigger another VM Exit to the L0 hypervisor. This L1-to-L0 transition is incredibly expensive in terms of CPU cycles. L0 must save L1’s state, load its own, process the request on behalf of L2, save its own state, and then resume L1, which in turn resumes L2. This cascade of context switching creates significant latency.

Shadow VMCS and EPT

To mitigate this, KVM has long used “shadowing” techniques. The key data structure for managing a VM’s state on Intel VT-x is the Virtual Machine Control Structure (VMCS). When L1 tries to configure the VMCS for L2, KVM (L0) intercepts this and maintains a “Shadow VMCS.” L0 populates the real VMCS for the L2 guest based on the settings L1 provides in the shadow structure, preventing L1 from directly manipulating hardware state.

A similar concept applies to memory virtualization with Extended Page Tables (EPT). L0 manages the real EPT that maps guest physical addresses to host physical addresses. When L1 tries to create an EPT for L2, L0 creates a “Shadow EPT” that combines the memory mappings of both L1 and L2. While effective, creating and maintaining these shadow structures adds complexity and overhead, contributing to performance degradation.

When setting up an L1 guest that will act as a hypervisor, you need to ensure its CPU model exposes the necessary virtualization features. Here is a libvirt XML example for an L1 guest.

<domain type='kvm'>

<name>l1-hypervisor</name>

<memory unit='KiB'>8388608</memory>

<vcpu placement='static'>4</vcpu>

<os>

<type arch='x86_64' machine='pc-q35-8.0'>hvm</type>

<boot dev='hd'/>

</os>

<features>

<acpi/>

<apic/>

<vmx/> <!-- Explicitly enable VMX for the guest -->

</features>

<cpu mode='host-passthrough' check='partial'>

<feature policy='require' name='vmx'/>

</cpu>

<!-- ... other disk and network configurations ... -->

</domain>This configuration, used in many Linux server news articles about virtualization, ensures the L1 guest has the VMX feature enabled, allowing it to function as a hypervisor.

Section 3: The Breakthrough: Enlightened VMCS in KVM

The latest Linux kernel news highlights a fundamental shift in how KVM handles nested VMX operations. Instead of relying solely on costly interception and shadowing for every VMCS access, the new approach “enlightens” the L1 hypervisor, making it aware that it’s running in a virtualized environment and allowing it to perform certain operations more directly and efficiently.

How Enlightened VMCS Works

The core idea is to divide the VMCS fields into two categories: “clean” fields and “sensitive” fields.

- Clean Fields: These are parts of the VMCS that primarily define the L2 guest’s state (e.g., guest general-purpose registers, instruction pointer, flags). Modifying these fields does not compromise the L0 host’s stability or security.

- Sensitive Fields: These fields control the virtualization behavior itself (e.g., host state, VM-exit controls, EPT pointer). Allowing L1 to write to these directly would be a major security risk.

With the new patches, KVM on L0 can expose a modified VMCS structure to the L1 hypervisor. When L1 needs to modify a “clean” field for its L2 guest, it can now write directly to a shared memory page that maps to the real L2 VMCS managed by L0. This action no longer requires a VM Exit from L1 to L0. L0 pre-validates the access and sets up the permissions, effectively creating a “fast path” for frequent, safe operations.

However, if L1 attempts to modify a “sensitive” field, the hardware triggers a VM Exit to L0 as before, ensuring the host remains in control. This hybrid approach delivers the best of both worlds: the security of interception for critical operations and the performance of direct access for common state changes.

To visualize the impact, consider this pseudocode representation of a VM-write operation from L1.

// --- OLD METHOD (Heavy VM Exits) ---

void l1_writes_to_l2_vmcs(field, value) {

// This entire function runs in L1 guest mode.

// The vmx_write instruction will *always* trap.

vmx_write(field, value);

// ^ This triggers a VM Exit from L1 to L0.

// L0 intercepts, validates, updates the shadow VMCS,

// and then resumes L1. This is very slow.

}

// --- NEW ENLIGHTENED METHOD ---

void l1_writes_to_enlightened_l2_vmcs(field, value) {

// KVM (L0) has mapped the "clean" fields page for us.

if (is_clean_field(field)) {

// No VM Exit! L1 writes directly to a shared memory location

// that L0 uses for the real L2 VMCS. This is extremely fast.

enlightened_vmcs_page->field = value;

} else {

// For sensitive fields, we still need to trap to L0.

vmx_write(field, value);

// ^ This triggers a VM Exit, preserving security.

}

}This optimization is a game-changer for workloads that frequently change the L2 guest’s state, such as those involving heavy context switching or system calls inside the nested guest. This is a significant piece of KVM news for anyone in the Linux DevOps space.

Section 4: Best Practices, Benchmarking, and Real-World Impact

These kernel enhancements will have a profound impact on various use cases. Cloud providers can offer more performant nested virtualization solutions. DevOps teams using tools like Kubernetes Linux news-worthy Minikube or Kind in virtualized CI/CD runners will see faster pipeline execution. Developers on Pop!_OS or Manjaro running Windows or macOS in a VM for cross-platform development will also benefit if they nest further layers.

Best Practices for Optimal Nested Performance

- Stay Current: The most important rule is to use a modern Linux kernel on your L0 host. These features will be mainlined in upcoming kernel releases. Distributions that follow the latest kernels, like Fedora and Arch Linux, will receive these updates first. For LTS distros like Ubuntu or Rocky Linux, you may need to wait for a new release or use a hardware enablement (HWE) kernel.

- Use Virtio Drivers: Always use virtio drivers for networking and block devices in both your L1 and L2 guests. This minimizes I/O emulation overhead, which is a separate but equally important performance factor.

- CPU and Memory Allocation: Do not overprovision CPUs. Allocate a realistic number of cores to your L1 guest. Ensure L1 has enough memory to run its own OS and also allocate sufficient memory to its L2 guests without causing swapping.

- Monitor VM Exits: Use performance monitoring tools to understand your workload. The `perf` tool in Linux can be used to count KVM-related events, including VM exits. A reduction in `kvm_exit` events for a given workload is a strong indicator of performance improvement.

Here is a simple example of using `perf` to monitor KVM events while a VM is running. You would first get the process ID (PID) of the QEMU process for your VM.

# Find the PID of your running QEMU/KVM virtual machine

QEMU_PID=$(pgrep -f "qemu-system-x86_64.*vm-name")

# Monitor KVM-related events for that specific process for 10 seconds

# A lower count for kvm_exit and kvm_vmx_nested_vmexit is better.

echo "Monitoring KVM events for PID $QEMU_PID..."

sudo perf stat -e 'kvm:*' -p $QEMU_PID -- sleep 10Finally, here’s a `virt-install` command, a popular tool in the Linux administration news cycle, to create an L1 guest, ensuring the CPU features are correctly passed through.

#!/bin/bash

# A script to create an L1 guest ready for nesting

virt-install \

--name l1-hypervisor-host \

--ram 8192 \

--vcpus 4 \

--disk path=/var/lib/libvirt/images/l1-host.qcow2,size=50 \

--os-variant fedora-server-latest \

--network bridge=virbr0,model=virtio \

--graphics none \

--console pty,target_type=serial \

--location 'https://download.fedoraproject.org/pub/fedora/linux/releases/39/Server/x86_64/os/' \

--extra-args 'console=ttyS0,115200n8' \

--cpu host-passthroughUsing `host-passthrough` is the simplest way to ensure all necessary CPU features, including VMX, are exposed to the L1 guest, making it capable of running L2 VMs efficiently.

Conclusion: The Future of Nested Virtualization is Bright

The introduction of enlightened VMCS handling in KVM for Intel processors marks a significant milestone in the evolution of Linux virtualization. By intelligently reducing the overhead associated with nested VM Exits, these kernel enhancements directly address a long-standing performance bottleneck. This is not just an incremental improvement; it’s a fundamental architectural shift that unlocks new levels of efficiency for cloud computing, complex development environments, and security sandboxing.

For system administrators, DevOps professionals, and anyone invested in the Linux ecosystem, the key takeaway is clear: keeping your host systems updated with the latest kernel versions is more critical than ever. As these changes propagate through major distributions, the performance gap between native and nested virtualization will narrow considerably, making powerful nested setups a more viable and attractive option for a wider range of applications. This advancement reaffirms KVM’s position as a leading, high-performance hypervisor and demonstrates the power of continuous innovation within the open-source community.