DoH is a Nightmare for Linux Server Security

Actually, I should clarify – I spent three hours last Tuesday staring at a packet capture from one of our staging servers that made absolutely no sense. The intrusion detection system (IDS) was screaming about a potential beacon, but my DNS logs? Squeaky clean. Nothing. Not a single query to a suspicious domain. Just the usual chatter to the local resolver.

It drove me up the wall.

But then it hit me. I filtered for port 443 and saw a steady stream of connections to 8.8.4.4 and 1.1.1.1. The malware wasn’t using the system DNS. It was probably using DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH) to bypass my monitoring entirely, tunneling commands right through the encrypted noise of legitimate web traffic.

This isn’t just a theoretical bypass anymore. If you manage Linux infrastructure in 2026, you need to realize that the “privacy” features we cheered for a few years ago have become the perfect cover for advanced persistent threats (APTs). The recent chatter about state-sponsored actors abusing this on Linux boxes isn’t hype. It’s exactly what I’m seeing in the wild.

The UDP/53 Era is Over (And I Miss It)

Back in the day—and by that I mean like, 2023—catching Linux malware was often as simple as watching UDP port 53. But now? Malware authors have realized that Linux servers often have strict egress filtering but almost always allow outbound HTTPS (TCP/443). By embedding a DoH client directly into the binary, they don’t touch /etc/resolv.conf. They don’t make system calls that auditd easily flags as DNS activity. They just open a TLS socket to Cloudflare or Google and ask for TXT records containing their next instructions.

To the firewall, it looks like an admin running curl or a package update. To the IDS, it’s just encrypted blob data. It’s actually kind of brilliant, in a terrifying, “I hate my job” sort of way.

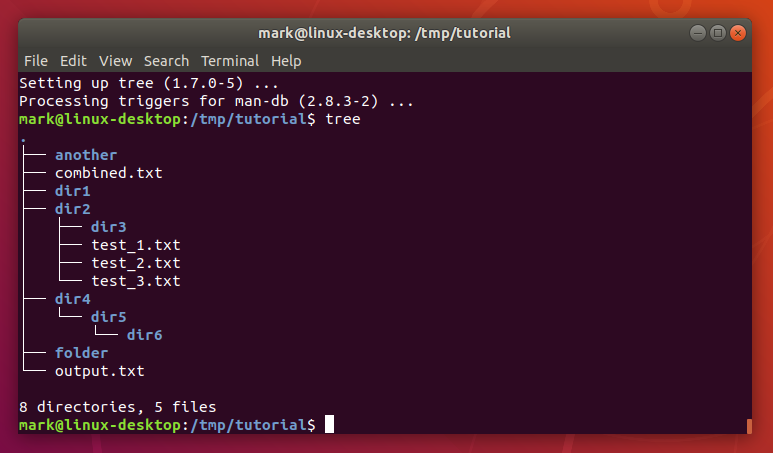

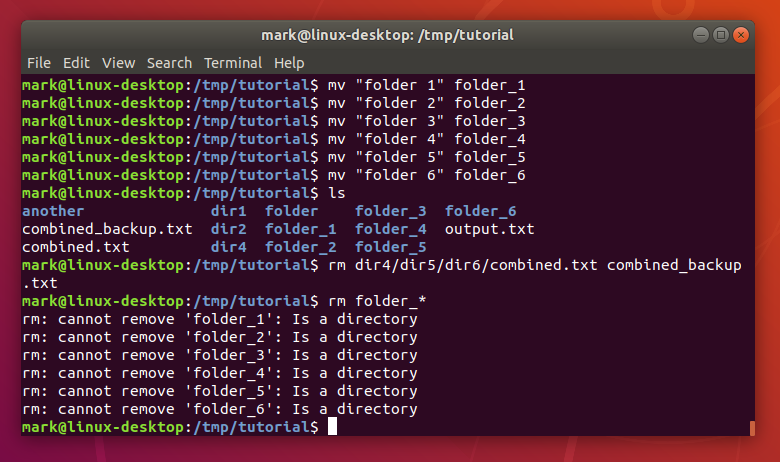

My “Lab” Experiment: Breaking My Own Rules

I wanted to see just how invisible this traffic really is, so I set up a test environment on my home lab (running Ubuntu 24.04 LTS on a couple of NUCs). And the result? Zeek’s dns.log was empty. Completely empty regarding the C2 domain. The ssl.log showed connections to Google, but since the SNI (Server Name Indication) was legitimate (dns.google), it didn’t raise any reputation flags.

How to Actually Detect This (Without Going Crazy)

So, are we screwed? Not entirely. But we have to stop thinking about “DNS monitoring” and start thinking about “Traffic Pattern Analysis.” Legitimate servers rarely talk to public DoH resolvers unless they are configured to do so. Your database server shouldn’t be chatting with Cloudflare’s DoH endpoint at 3 AM.

Here’s a Python script I hacked together using scapy to parse a PCAP and flag potential DoH usage based on SNI. It’s rough, but it saved my bacon during that investigation last week.

from scapy.all import *

from scapy.layers.tls.all import TLSClientHello

# Known DoH providers - add more as you find them

DOH_SNI_LIST = [

b'dns.google',

b'cloudflare-dns.com',

b'doh.opendns.com',

b'dns.quad9.net'

]

def analyze_packet(pkt):

if pkt.haslayer(TLSClientHello):

# Extract SNI

try:

sni = pkt[TLSClientHello].ext[0].servername

if sni in DOH_SNI_LIST:

src_ip = pkt[IP].src

print(f"[ALERT] DoH Traffic Detected from {src_ip} to {sni.decode()}")

except Exception:

pass

# Read your capture file

# I usually capture with: tcpdump -i eth0 -w capture.pcap port 443

print("Scanning for DoH SNIs...")

sniff(offline="capture.pcap", prn=analyze_packet, store=0)The “Ban It All” Approach

Honestly, for most server environments, the safest play right now is to block known public DoH resolvers at the firewall level. I know, I know—it feels like playing Whac-A-Mole. But if your servers are supposed to use your internal Bind or Active Directory DNS, they have zero business talking to 1.1.1.1 over HTTPS.

Another thing? Look at your process lists. I noticed that the malware often names itself something innocuous like systemd-resolve (nice try), but running lsof -p [PID] reveals it holds a TCP socket to a public IP on port 443, not a UDP socket to your local gateway. That discrepancy is a smoking gun.

Where This Goes Next

The cat-and-mouse game is shifting. By mid-2027, I expect we’ll see malware moving away from public DoH resolvers entirely and hosting their own DoH endpoints on compromised legitimate sites. Imagine malware using a compromised WordPress blog as a DoH resolver. The traffic would look like regular HTTPS to a blog. Good luck blocking that with an SNI list.

For now, though? Check your egress logs. If you see high-volume HTTPS traffic to Google or Cloudflare from a headless Linux server that isn’t running a web browser, start digging. You might not like what you find.