Why I quit Arch for Slackware in 2026

Actually, I should clarify — it was 2:14 AM on a Tuesday. My laptop fan was screaming, and I was staring at a black screen with white text that essentially told me my graphics driver and kernel were no longer on speaking terms. I had just run a standard update on my rolling release distro of choice. But looking at the error logs, I realized I just didn’t care enough to fix it anymore.

I reached into my drawer, grabbed a dusty SanDisk drive, and flashed the latest Slackware image. And I haven’t looked back since.

In 2026, running Slackware feels like driving a manual transmission truck in a world of self-driving electric pods. It requires attention. But when you turn the wheel, the wheels actually turn. There’s no abstraction layer guessing what you really meant to do.

The “Current” State of Affairs

Most people think of Slackware as that fossilized distro from the 90s that uses floppy disks. But if you’re running the -current branch in 2026, you’re basically on a rolling release that doesn’t break every time a developer sneezes.

I’m currently running Kernel 6.13.2 on my ThinkPad T14 Gen 4. The difference between Slackware’s “rolling” and other distros is the philosophy of updates. Patrick Volkerding (the benevolent dictator for life) doesn’t just push packages because the version number went up. They get pushed when they work.

Last week, I updated my entire KDE Plasma stack to 6.3.1. On other distros, this usually results in a few days of broken widgets or weird compositor glitches. But on Slackware? It just reloaded. The config files weren’t overwritten. My custom scripts in /etc/rc.d/ didn’t vanish.

Dependency Hell is a Myth (Mostly)

The biggest criticism I hear is: “But it doesn’t resolve dependencies!” Good. I don’t want it to.

When I install a package on a modern “user-friendly” distro, it often pulls in 400MB of dependencies I didn’t ask for. But with Slackware, if I install something and it’s missing a library, the binary tells me. I find that library. I install it. I know exactly what is on my system.

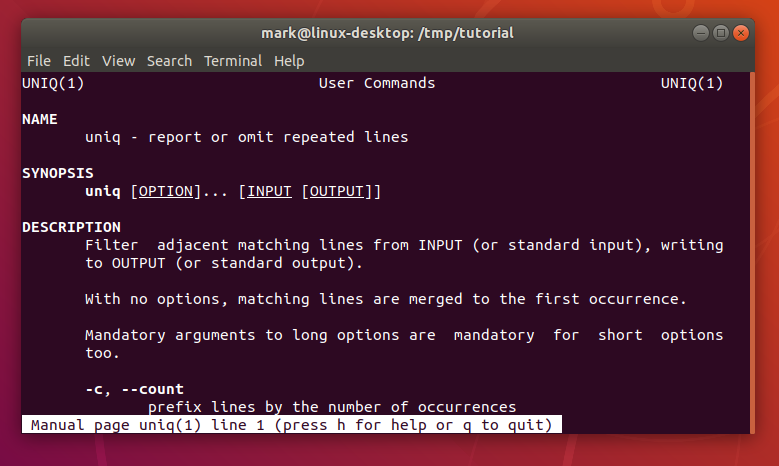

For the lazy moments (we all have them), there’s sbopkg. I use it to pull builds from SlackBuilds.org. It’s not a package manager in the traditional sense; it’s a build script manager. It compiles from source, optimized for my architecture.

Original Analysis: Memory Footprint in 2026

I wanted to see if the “lightweight” reputation still held up against modern competitors. The results were actually shocking. I expected them to be close.

- Fedora 44 Idle RAM: 1.4 GB

- Slackware Current Idle RAM: 580 MB

Where did that extra gigabyte go on Fedora? Background services. Telemetry agents. Update daemons. Indexing services. PackageKit sitting there eating CPU cycles waiting for me to install something.

On Slackware, htop shows me a list of processes that fits on a single screen. There is no mystery meat running in the background. If a service is running, it’s because I typed chmod +x /etc/rc.d/rc.myservice.

The Systemd Question

Look, I’m not going to turn this into a holy war. But in 2026, avoiding systemd is becoming increasingly difficult. It has swallowed udev, homed, boot protocols, and DNS. Slackware remains one of the few sanctuaries of BSD-style init scripts.

Why does this matter? Debuggability. My startup script is a shell script. I can read it. I can edit it with vi. If it breaks, I can insert an echo "I made it here" line to debug it. Try doing that with a binary journal log or a complex unit file dependency chain when your system won’t boot.

Living with Flatpaks

I’m a purist, but I’m not a masochist. I need to use Discord. I need Spotify. I need Zoom for client calls. Compiling these proprietary blobs on Slackware is a nightmare I don’t wish on my worst enemy.

But it actually fits the philosophy perfectly. I keep my base system pure—kernel, shell, compilers, window manager. The messy, proprietary, fast-moving apps live in their own sandboxed containers where they can’t mess up my system libraries.

I ran into a snag last Tuesday with the Discord Flatpak not picking up my microphone input. But on Slackware, I knew exactly what was wrong: I hadn’t added my user to the audio group because I created the user manually. One command, a logout, and it was fixed.

Is it for you?

Probably not. If you want an app store, don’t use Slackware. If you want to install NVIDIA drivers by clicking a button, stay away. If you are afraid of the command line, run.

But if you’re tired of your operating system treating you like a guest instead of the owner, give it a shot. There is a profound sense of calm in knowing that your computer is doing exactly what you told it to do—nothing more, nothing less. In 2026, that kind of control is the ultimate luxury.