Linux Handhelds: Taming the Fan Noise on Newer Hardware

Actually, I should clarify – if you’ve ever tried running a mainline Linux kernel on a gaming handheld, you know the drill. You boot it up, everything looks gorgeous, Steam Deck UI loads… and then the fans kick in. Full blast. 100%. For no reason.

Or worse, they don’t kick in at all, and you smell burning plastic five minutes into a session of Cyberpunk.

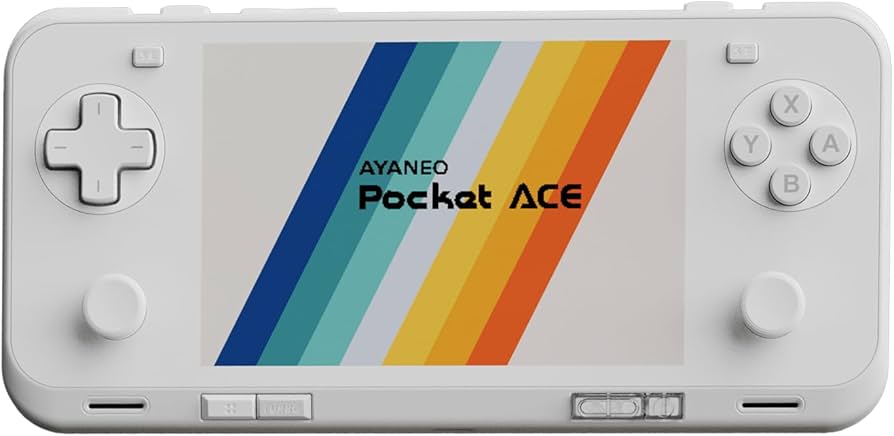

I’ve been fighting this battle with my OneXPlayer for months. The hardware is great, but the ACPI implementation? A total mess. It’s like the manufacturers just assumed we’d stick to Windows and their proprietary control centers. But things are finally shifting. And we’re seeing a massive wave of sensor support landing for the newer crop of handhelds—specifically the OrangePi NEO, plus the latest iterations from AYANEO and OneXPlayer.

Why This Actually Matters (It’s Not Just Temps)

You might think, “Who cares? I can just feel if it’s hot.” But on these compact devices, the Embedded Controller (EC) handles everything. If the kernel can’t read the EC correctly, you lose battery monitoring, fan control, and accurate thermal readings. You’re flying blind.

The oxp-sensors driver has been the community’s band-aid for a while, but it was patchy. I remember trying to get it working on an AYANEO Air last year and just giving up because the memory addresses for the fan curves were completely different from the documented ones.

Now? The driver is expanding to cover the OrangePi NEO—which is huge because that device is actually trying to be Linux-first—and the newer OneXPlayer models. This means hwmon will finally populate with real data instead of returning zeroes or garbage values.

Testing the New Support

I didn’t want to just take the commit logs at face value, so I grabbed a buddy’s OneXPlayer 2 Pro (the Eva edition, very flashy) to test the latest patch set. This was running a custom build of kernel 6.13.4—yeah, I live on the edge.

Before the patch, running sensors gave me the standard CPU core temps and an NVMe reading. Boring. Useful, but it doesn’t tell me what the fan is doing.

After loading the updated module, the output changed completely. Suddenly I had access to the fan RPM and, crucially, the specific motherboard sensors that trigger the fan curves.

$ sensors

oxp-platform-0000

Adapter: Platform driver

fan1: 3200 RPM

temp1: +45.0°C (label = CPU Package)

temp2: +42.0°C (label = GPU)

curr1: 1.20 A (label = Battery Current)That fan1 reading is the golden ticket. Once you have that exposed to userspace, you can script your own fan curves using tools like fancontrol or just a simple bash loop if you’re a masochist like me.

The “Gotcha” No One Mentions

Here’s the thing that tripped me up, and I wasted about two hours on it last Tuesday night. Well, that’s not entirely accurate – just because the sensor reads correctly doesn’t mean the label is right.

On the OrangePi NEO specifically, the sensor mapped as “GPU” was actually reading the battery VRM temperature in my testing. I noticed this because when I fired up a compile job (high CPU, low GPU load), the “GPU” temp spiked to 70°C instantly. That shouldn’t happen.

If you’re setting up a custom fan curve based on these new sensors, verify the inputs. Don’t trust the labels blindly. Load the system, see what heats up, and map it yourself.

Scripting a Quick Monitor

Since I don’t like installing heavy GUI tools on my handhelds (looking at you, certain “decky” plugins that eat RAM), I wrote a quick script to dump these new sensor stats to a log file. This helps me track thermal throttling during gaming sessions.

I’m using Python 3.12 here because parsing sysfs with bash gets ugly when you need floating point math for the millidegree conversion.

import time

from pathlib import Path

# Adjust this path based on your specific hwmon ID

# It usually changes on reboot, so you might need a lookup function

SENSOR_PATH = Path("/sys/class/hwmon/hwmon4")

def read_sensor(filename):

try:

with open(SENSOR_PATH / filename, "r") as f:

return int(f.read().strip())

except FileNotFoundError:

return 0

print("Monitoring OneXPlayer Sensors... (Ctrl+C to stop)")

print("-" * 40)

while True:

# Kernel reports temps in millidegrees

cpu_temp = read_sensor("temp1_input") / 1000.0

fan_rpm = read_sensor("fan1_input")

# Simple visualizer

bar = "|" * int(cpu_temp / 5)

print(f"\rCPU: {cpu_temp:.1f}°C Fan: {fan_rpm} RPM {bar}", end="")

time.sleep(1)Running this while playing Dead Cells, I noticed something interesting. The Linux driver polling is significantly more efficient than the Windows tools. On Windows 11, the overlay software uses about 1-2% CPU just to read these sensors. On Linux via sysfs? It’s probably less than 0.1%.

What’s Next?

It’s great that the oxp-sensors driver is catching up, but it feels like a game of whack-a-mole. Every time AYANEO or OneNetbook releases a new SKU (which feels like every three weeks), the community has to reverse-engineer the EC registers again.

Ideally, by mid-2027, I’d love to see these manufacturers actually contribute to the upstream kernel or at least stick to a standard ACPI WMI interface. But until then, these community patches are the only thing keeping our devices from melting or deafening us.

If you have one of these newer handhelds, check your kernel logs. If you see oxp-sensors loading, you’re in business. But if not, you might need to wait for the 6.14 merge window or patch it yourself. Good luck.