The Future of Linux Scheduling: How `sched_ext` and BPF are Revolutionizing Performance on Raspberry Pi and Beyond

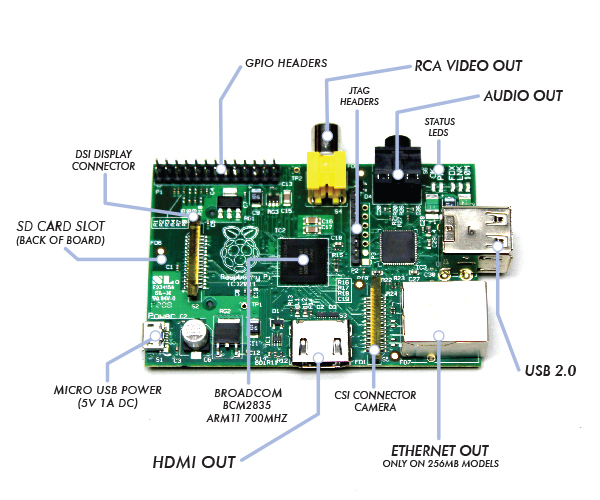

The Linux kernel, the core of countless operating systems from massive cloud servers to the tiny Raspberry Pi, is a masterpiece of engineering. One of its most critical components is the process scheduler—the maestro that decides which task gets to use the CPU and for how long. For decades, this core logic has been a monolithic, C-coded part of the kernel, accessible only to seasoned kernel developers. However, a revolutionary change is underway. The recent integration of `sched_ext` marks a paradigm shift, allowing developers and administrators to write and deploy custom scheduling policies as eBPF programs. This development, part of the exciting wave of Linux kernel news, unlocks unprecedented flexibility and performance tuning capabilities, with profound implications for the entire ecosystem, especially for versatile hardware like the Raspberry Pi.

This article dives deep into the world of `sched_ext` and BPF-based scheduling. We’ll explore the core concepts, examine practical code examples for creating your own scheduler, and discuss the real-world applications this technology enables, from real-time embedded systems to high-performance computing. This is a significant piece of Linux development news that will shape the future of system performance and optimization across all major distributions, from Debian news and Ubuntu news to the rolling releases of Arch Linux news.

The Pillars of Performance: Deconstructing the Linux Scheduler and eBPF

To fully appreciate the significance of `sched_ext`, we must first understand the two technologies it marries: the traditional Linux scheduler and the extended Berkeley Packet Filter (eBPF). These components represent the old guard and the new wave of kernel programmability.

The Traditional Linux Scheduler: A Quick Refresher

The Linux kernel employs several scheduling policies, each designed for different types of workloads. The most common is the Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS), which is the default for standard processes. CFS aims to give every task a fair share of CPU time, ensuring that no single process starves the others. It’s a brilliant general-purpose scheduler that works exceptionally well for desktops and servers running a mix of applications.

For workloads with stricter timing requirements, the kernel provides real-time policies like FIFO (First-In, First-Out) and RR (Round-Robin). These are crucial for applications where latency is critical, a topic central to Linux real-time news. However, the fundamental limitation of this architecture is its rigidity. Modifying scheduling behavior requires changing the kernel’s C source code, recompiling it, and rebooting the system—a complex and disruptive process. This one-size-fits-all approach, while robust, isn’t always optimal for specialized hardware or unique application demands, a challenge often faced in Linux embedded news and on platforms like the Raspberry Pi.

Enter eBPF: The In-Kernel Virtual Machine

eBPF (extended Berkeley Packet Filter) has evolved far beyond its origins as a tool for filtering network packets. Today, it functions as a lightweight, sandboxed virtual machine inside the Linux kernel. It allows developers to write small, efficient programs that can be safely loaded and executed at various hook points within the kernel without requiring kernel modifications or module loading.

The magic of eBPF lies in its safety and performance. Before a BPF program is loaded, it undergoes a rigorous check by an in-kernel verifier. This verifier analyzes the code to ensure it won’t crash the system, access arbitrary memory, or contain infinite loops. Once verified, the BPF bytecode is Just-In-Time (JIT) compiled into native machine code for near-native execution speed. This has made eBPF a cornerstone of modern Linux observability news (with tools like Prometheus and Grafana), Linux networking news (powering projects like Cilium), and Linux security news (for runtime threat detection).

`sched_ext`: A Deep Dive into Programmable Scheduling

`sched_ext` is the framework that finally brings the power of eBPF to the core process scheduler. It introduces a new scheduling class that acts as a dispatcher, handing off key scheduling decisions to a loaded BPF program. This allows a userspace application to define the entire scheduling policy for a set of CPUs, effectively replacing CFS on those cores.

How `sched_ext` Works

The `sched_ext` framework provides a set of essential hooks that a BPF program can implement to manage the lifecycle of a task. These hooks are called by the kernel at critical moments in the scheduling process. Some of the key operations include:

- select_task: The most important hook. The kernel calls this when a CPU becomes idle, asking the BPF program which task should run next.

- enqueue_task: Called when a new task becomes runnable (e.g., it wakes up from sleep or is newly created). The BPF program uses this to add the task to its run queue.

- dequeue_task: Called when a task is no longer runnable (e.g., it goes to sleep or exits).

- preempt: Called to check if the currently running task should be preempted by another, more urgent task.

The BPF program typically uses BPF maps—a generic key/value store in the kernel—to maintain its own run queues and track task state. This separation allows for incredible flexibility in designing scheduling algorithms.

Your First BPF Scheduler: A Code Example

Let’s look at a simplified BPF scheduler written in C. This example implements a basic First-In, First-Out (FIFO) logic using a BPF map as a run queue. This code would be compiled using a toolchain like LLVM/Clang. This is a prime example of cutting-edge C Linux news and Linux programming news.

#include <vmlinux.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

// Define a simple linked-list node for our run queue

struct scx_bpf_task {

struct bpf_list_node node;

u64 enq_time; // Timestamp when the task was enqueued

};

// BPF map to store task-specific data

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_TASK_STORAGE);

__uint(map_flags, BPF_F_NO_PREALLOC);

__type(key, int);

__type(value, struct scx_bpf_task);

} task_storage SEC(".maps");

// BPF map to act as our run queue (a linked list)

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_PERCPU_ARRAY);

__uint(max_entries, 1);

__type(key, int);

__type(value, struct bpf_list_head);

} run_queue SEC(".maps");

// Helper to get the per-CPU run queue

static struct bpf_list_head *get_rq(void) {

int zero = 0;

return bpf_map_lookup_elem(&run_queue, &zero);

}

// Enqueue a task: add it to the tail of the run queue

SEC("sched_ext/enqueue_task")

int BPF_PROG(enqueue_task, struct task_struct *p, int cpu, int enq_flags) {

struct scx_bpf_task *bpf_task;

struct bpf_list_head *rq;

bpf_task = bpf_task_storage_get(&task_storage, p, 0,

BPF_LOCAL_STORAGE_GET_F_CREATE);

if (!bpf_task)

return -1;

rq = get_rq();

if (!rq)

return -1;

bpf_task->enq_time = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

bpf_list_push_back(rq, &bpf_task->node);

return 0;

}

// Select a task: get the head of the run queue

SEC("sched_ext/select_task")

struct task_struct *BPF_PROG(select_task, int cpu) {

struct bpf_list_head *rq = get_rq();

struct scx_bpf_task *bpf_task;

struct task_struct *p;

if (!rq)

return NULL;

bpf_task = bpf_list_pop_front(rq, struct scx_bpf_task, node);

if (!bpf_task)

return NULL;

// Get the task_struct from the task storage pointer

p = bpf_task_get_task(bpf_task);

return p;

}

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "GPL";This code defines two BPF maps: one for storing our custom task data (`task_storage`) and another to serve as a per-CPU run queue (`run_queue`). The `enqueue_task` function adds a new task to the back of the list, while `select_task` pulls the next task from the front, implementing simple FIFO behavior.

Unleashing Potential: Real-World Applications for BPF Schedulers

The ability to dynamically program the scheduler opens a vast landscape of possibilities. This isn’t just an academic exercise; it has tangible benefits for a wide range of use cases, from Linux IoT news to large-scale Linux server news.

Optimizing for Raspberry Pi and Embedded Systems

The Raspberry Pi, particularly recent models with heterogeneous cores (like big.LITTLE architecture), is a perfect candidate for custom schedulers. A BPF scheduler could be written to intelligently place tasks:

- Real-Time Robotics: A scheduler could guarantee that a motor control process always runs with minimal latency, while logging tasks are relegated to efficiency cores.

- Media Centers: Prioritize video decoding and audio processing threads to eliminate stuttering, a common goal in Linux audio news and graphics.

- Power-Aware IoT: For battery-powered devices, a scheduler could aggressively put the CPU to sleep, waking only for brief, critical events, dramatically extending battery life.

Loading and Managing Your BPF Scheduler

Once you’ve compiled your BPF scheduler (e.g., to `sched_fifo.o`), you need to load it. This is typically done with the `bpftool` utility, a key part of modern Linux administration news.

# 1. Load the BPF object file into the kernel

bpftool prog load sched_fifo.o /sys/fs/bpf/sched_fifo

# 2. Attach the scheduler to a specific CPU (e.g., CPU 3)

# This command effectively replaces the default CFS scheduler on that core.

bpftool sched attach /sys/fs/bpf/sched_fifo cpu 3

# To see the status of your scheduler

bpftool sched show

# To detach and revert to the default scheduler

bpftool sched detach cpu 3This command-line interaction demonstrates how dynamically you can swap scheduling policies without a reboot, a game-changer for Linux DevOps news and agile system tuning.

Interacting with Schedulers from High-Level Languages

The programmability extends beyond the kernel. Userspace applications can interact with BPF maps to monitor or even influence the scheduler’s behavior. The BCC (BPF Compiler Collection) project provides powerful Python bindings for this purpose.

Imagine our scheduler stored performance metrics in a BPF map. A Python script could read this map to visualize run queue latency in real-time. This is a powerful concept for Linux monitoring news.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from bcc import BPF

import time

# BPF program (can be in-line or from a file)

# This is a conceptual example. A real one would need

# a BPF map named 'stats' in the scheduler C code.

bpf_text = """

#include <uapi/linux/ptrace.h>

BPF_HASH(stats, u64);

// Assume a function in the scheduler updates this map

// void update_latency_stat(u64 latency) {

// u64 key = 0;

// u64 *val = stats.lookup_or_try_init(&key, &latency);

// if (val) {

// *val = latency;

// }

// }

"""

# Load the BPF program

# In a real scenario, you'd attach to the existing scheduler's maps

# rather than loading a new program. This is for demonstration.

# b = BPF(text=bpf_text)

# stats_map = b.get_table("stats")

print("Reading scheduler stats (conceptual)...")

# while True:

# try:

# for k, v in stats_map.items():

# print(f"Average latency: {v.value} ns")

# time.sleep(2)

# except KeyboardInterrupt:

# exit()

print("This example is conceptual to show Python/BCC interaction.")

print("A real implementation would attach to the maps of the already-loaded scheduler.")

This synergy between in-kernel BPF and userspace scripting with languages like Python is a powerful trend in Python Linux news, enabling sophisticated, custom system analysis and control.

Navigating the New Frontier: Best Practices and Considerations

While `sched_ext` is incredibly powerful, it’s a tool that requires care and understanding. Giving userspace the ability to control core scheduling logic is a significant responsibility.

Security and Stability: The Role of the BPF Verifier

The primary safety net is the BPF verifier. It ensures that a BPF scheduler cannot harm the kernel. It statically proves that the program will always terminate, won’t access invalid memory, and adheres to strict programming constraints. This robust sandboxing is what makes `sched_ext` viable. However, a poorly written scheduler can still lead to performance degradation or live-locking a CPU, where no useful work gets done. Thorough testing and gradual rollout are essential.

Performance and Debugging

While JIT-compiled BPF is fast, it may not always match the performance of a hand-tuned, native C scheduler like CFS. The overhead of BPF map lookups and the general nature of the `sched_ext` framework can introduce minor latency. The key is that for many workloads, the benefits of a custom-tailored policy will far outweigh this slight overhead. Debugging can also be challenging. Tools like `bpftrace` and the logging capabilities of `bpf_printk` are invaluable for understanding what your BPF scheduler is doing inside the kernel.

The Impact on the Linux Ecosystem

The introduction of `sched_ext` will have a ripple effect across the Linux world. As distributions like Fedora news, openSUSE news, and enterprise players in Red Hat news adopt kernels 6.12 and later, this capability will become widely available. It complements other recent advancements, such as the full integration of `PREEMPT_RT` for real-time performance and improved hardware support for devices like the Raspberry Pi 5. This convergence of features is creating a more flexible, powerful, and adaptable Linux kernel than ever before, impacting everything from Linux gaming news, where low input latency is key, to Kubernetes Linux news, where custom schedulers could optimize pod placement based on application-specific metrics.

Conclusion: A Paradigm Shift in Linux Kernel Development

The arrival of `sched_ext` is far more than just another kernel feature; it represents a fundamental shift in the philosophy of Linux kernel development. It moves the kernel away from a monolithic, one-size-fits-all design towards a more programmable, modular, and dynamic core. By empowering developers and system administrators to craft and deploy bespoke scheduling policies with the safety and performance of eBPF, Linux is becoming more adaptable to the diverse workloads of the modern computing landscape.

For Raspberry Pi enthusiasts, IoT developers, and performance engineers, this is a call to action. The era of being limited by a generic scheduler is ending. Now is the time to experiment, to build schedulers tailored for your specific needs—whether that’s for a low-latency audio project, a power-efficient sensor node, or a high-throughput web server. The tools are here, the kernel is ready, and the potential for innovation is limitless.