The Vibrant World of Linux Text Editors: A Deep Dive into the Modern Developer’s Toolkit

For any developer, sysadmin, or data scientist working on a Linux system, the text editor is more than just a tool—it’s the central hub of productivity. It’s where code is born, configurations are sculpted, and ideas take shape. While other operating systems often rally around one or two “killer app” editors, the Linux ecosystem has cultivated a remarkably diverse and powerful landscape of its own. The latest Linux text editors news isn’t about waiting for ports from other platforms; it’s about the constant innovation happening within the open-source community itself. From the command-line titans that have powered developers for decades to the modern graphical interfaces that rival any proprietary offering, the choice and power available to users of Ubuntu, Fedora, Arch Linux, and beyond have never been greater.

This article explores the current state of text editing on Linux, diving into the philosophies, features, and recent developments of the most influential editors. We’ll examine practical configurations, showcase how modern features like the Language Server Protocol (LSP) are unifying the experience, and demonstrate why the Linux development environment remains a first-class citizen, driven by its own powerful, community-forged tools.

The Enduring Power of Modal Editing: Vim and Neovim

For many who live in the terminal, modal editing isn’t just a feature; it’s a philosophy. The ability to switch between a command mode for manipulation and an insert mode for typing is the cornerstone of efficiency for millions. Vim, the venerable and ubiquitous editor, is a testament to this power. It’s pre-installed on nearly every Linux distribution, from Debian news and Red Hat news servers to lightweight Alpine Linux containers, making it an essential skill for any Linux administrator or DevOps professional.

Vim: The Ubiquitous Standard

Vim’s strength lies in its simplicity, rock-solid stability, and deep integration with the Unix philosophy. Its configuration, typically handled in a ~/.vimrc file, allows for extensive customization through Vimscript. While sometimes considered arcane, mastering Vim’s motions and commands unlocks a level of speed that is difficult to match with a mouse-driven interface.

A basic but practical .vimrc can dramatically improve the out-of-the-box experience:

" A simple and effective .vimrc configuration

" Enable syntax highlighting

syntax on

" Use filetype-specific indentation and plugins

filetype plugin indent on

" Set line numbers

set number

" Set relative line numbers for easier vertical navigation

set relativenumber

" Use 4 spaces for tabs

set tabstop=4

set shiftwidth=4

set expandtab

" Enable smart case-insensitive searching

set ignorecase

set smartcase

" Highlight search results

set hlsearch

" Show matching brackets

set showmatchNeovim: The Modern Successor

Recent Neovim news highlights its meteoric rise as a fork of Vim focused on modernization and extensibility. Neovim refactored the original codebase to enable better asynchronous processing, a crucial feature for modern tools like language servers and linters. Its most significant contribution is its first-class support for Lua as a configuration and plugin language. This has fostered a vibrant ecosystem of fast, modern plugins that are often easier to write and maintain than their Vimscript counterparts.

Neovim’s adoption of the Language Server Protocol (LSP) out-of-the-box has made it a favorite for Linux programming news, turning the terminal editor into a full-fledged IDE. Setting up a modern Neovim configuration often involves a plugin manager like lazy.nvim and configuring LSP clients.

Developer coding on Linux computer – What Is Open-Source Software? (With Examples) | Indeed.com

Here’s an example of an init.lua file to set up lazy.nvim and install a theme and LSP configuration plugin:

-- Neovim init.lua using lazy.nvim package manager

local lazypath = vim.fn.stdpath("data") .. "/lazy/lazy.nvim"

if not vim.loop.fs_stat(lazypath) then

vim.fn.system({

"git",

"clone",

"--filter=blob:none",

"https://github.com/folke/lazy.nvim.git",

"--branch=stable", -- latest stable release

lazypath,

})

end

vim.opt.rtp:prepend(lazypath)

-- Set up lazy.nvim with plugins

require("lazy").setup({

-- A popular colorscheme

{ "ellisonleao/gruvbox.nvim" },

-- LSP configuration helper

{

"neovim/nvim-lspconfig",

dependencies = {

-- Automatically install LSPs

"williamboman/mason.nvim",

"williamboman/mason-lspconfig.nvim",

},

config = function()

-- Configure Mason to ensure Python's LSP (pyright) is installed

require("mason").setup()

require("mason-lspconfig").setup({

ensure_installed = { "pyright" },

})

-- Set up the pyright language server

require("lspconfig").pyright.setup({})

-- Optional: Set keymaps for LSP functionality

vim.keymap.set('n', 'K', vim.lsp.buf.hover, {})

vim.keymap.set('n', 'gd', vim.lsp.buf.definition, {})

end

},

})

-- Set the colorscheme after plugins are loaded

vim.cmd.colorscheme "gruvbox"GNU Emacs: The Extensible Lisp Machine

No discussion of Linux text editors is complete without mentioning GNU Emacs. Often described as “a great operating system, lacking only a decent text editor,” this statement, while humorous, hints at its true power. Emacs is fundamentally a Lisp interpreter, and its text editing capabilities are just one of its many applications. This architecture makes it infinitely extensible.

More Than an Editor

For decades, Emacs has been the tool of choice for users who want to live inside a single, unified environment. Its ecosystem includes world-class packages for:

- Org Mode: A legendary outlining, note-taking, and project planning tool.

- Magit: Widely considered the best Git interface ever created.

- mu4e: A powerful and fast email client.

This level of integration is a core part of Emacs news and its enduring appeal. Modern frameworks like Doom Emacs and Spacemacs have made it more accessible by providing curated, performance-tuned configurations with Vim-style modal editing, appealing to a new generation of developers on distributions like Manjaro news and EndeavourOS.

Configuring with Elisp

Emacs is configured using Emacs Lisp (Elisp). The modern standard for managing packages is the use-package macro, which simplifies configuration by co-locating package installation and setup code. Here’s a small snippet from an init.el file demonstrating how to install and configure a package:

;; Ensure package archives are set up

(require 'package)

(add-to-list 'package-archives '("melpa" . "https://melpa.org/packages/") t)

(package-initialize)

;; Bootstrap 'use-package'

(unless (package-installed-p 'use-package)

(package-refresh-contents)

(package-install 'use-package))

;; Example: Configure the 'which-key' package to show available keybindings

(use-package which-key

:ensure t ; Ensure the package is installed

:init (which-key-mode)) ; Enable the mode on startup

;; Example: Basic Python configuration

(use-package python-mode

:ensure t

:config

(setq python-shell-interpreter "python3"))The Rise of the Graphical Editor: VS Code and Its Kin

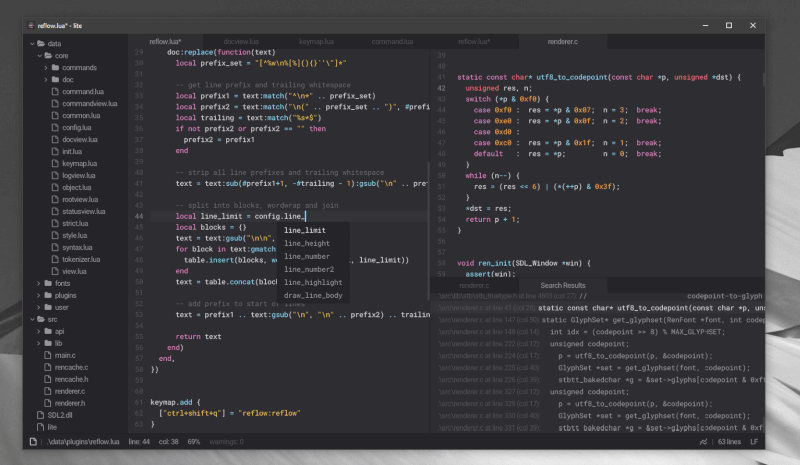

While terminal editors are immensely powerful, the modern graphical editor has become the dominant force on the Linux desktop news scene. Leading this charge is Microsoft’s Visual Studio Code. Its success is built on a foundation of performance, a user-friendly interface, and an unparalleled extension marketplace.

VS Code on Linux

VS Code offers a seamless experience on Linux, available through native package managers (apt, dnf) and universal formats like Flatpak news and Snap packages. Its key features include:

- IntelliSense: Powerful code completion, parameter info, and quick info.

- Integrated Debugger: An easy-to-use graphical debugger that supports numerous languages.

- Extensibility: A massive library of extensions for everything from themes and language support to Docker and Kubernetes integration.

This combination has made it incredibly popular in the Linux DevOps news and cloud-native development communities. Customizing VS Code is done through a simple JSON file, settings.json.

Here is a practical settings.json example for a Python developer on Linux, setting the terminal to Zsh and configuring the linter:

{

// General UI settings

"workbench.colorTheme": "Default Dark+",

"editor.fontSize": 14,

"editor.fontFamily": "'Fira Code', 'Droid Sans Mono', 'monospace', monospace",

"editor.fontLigatures": true,

// Integrated terminal settings

"terminal.integrated.defaultProfile.linux": "zsh",

"terminal.integrated.fontSize": 13,

// Python-specific settings

"[python]": {

"editor.defaultFormatter": "ms-python.black-formatter",

"editor.formatOnSave": true,

"editor.codeActionsOnSave": {

"source.organizeImports": "explicit"

}

},

"python.linting.pylintEnabled": true,

"python.linting.enabled": true,

// Git settings

"git.autofetch": true,

"git.confirmSync": false

}Best Practices and Unifying Technologies

Regardless of the editor you choose, several key trends and technologies are shaping the modern development workflow on Linux. Understanding these can help you build a more efficient and powerful environment.

The Language Server Protocol (LSP)

Perhaps the most significant development in recent years is the Language Server Protocol. Created by Microsoft, LSP standardizes communication between a text editor and a “language server” that provides features like autocompletion, diagnostics, and go-to-definition. This means a single language server (e.g., `pyright` for Python, `rust-analyzer` for Rust) can provide deep language intelligence to any editor that supports the protocol, including Neovim, Emacs, and VS Code. This has leveled the playing field, allowing terminal editors to gain IDE-like features that were once the exclusive domain of heavy graphical applications. This is a recurring theme in Python Linux news and Rust Linux news.

Configuration as Code and Dotfiles

A core tenet of the Linux philosophy is treating configuration as code. Your editor’s setup—your .vimrc, init.el, or settings.json—is a valuable asset. Best practice is to store these “dotfiles” in a Git repository. This provides several benefits:

- Version Control: Track changes to your configuration and revert if something breaks.

- Portability: Quickly set up your personalized environment on any new machine, whether it’s a new laptop running Pop!_OS or a cloud server from DigitalOcean.

- Sharing: Share your setup with others and learn from the community.

Tools like GNU Stow or custom shell scripts are often used to symlink these files from the Git repository to their correct locations in the home directory.

Terminal Integration

A seamless workflow between the editor and the shell is critical. VS Code’s integrated terminal is excellent, while Vim and Emacs users often rely on terminal multiplexers like `tmux` or Neovim’s built-in terminal emulator. This allows you to run build commands, execute scripts, and manage services without ever leaving your editing environment, a must for anyone following Linux CI/CD news or working with tools like Docker and Ansible.

Conclusion

The Linux text editor ecosystem is a vibrant, self-sufficient, and innovative space. The narrative is not one of waiting for external tools to arrive, but of a community continually refining its own powerful solutions. Whether you prefer the raw, keyboard-driven efficiency of Neovim, the all-encompassing, extensible world of Emacs, or the polished, feature-rich experience of VS Code, there is a world-class tool available that is deeply integrated with the Linux operating system.

The rise of open standards like the Language Server Protocol has further blurred the lines, bringing IDE-level intelligence to every editor. As a Linux user, the power lies in choice and customization. By investing time in mastering your chosen editor and embracing practices like managing your dotfiles, you can build a development environment that is not just functional, but a true extension of your workflow, perfectly tailored to your needs.