Mastering Linux File Permissions: The Unsung Guardian of System Security

The Foundation of a Secure System: Why Linux File Permissions Matter

In the vast and dynamic world of Linux, from enterprise servers running Red Hat Enterprise Linux to developer laptops powered by Pop!_OS or Fedora, one of the most fundamental and critical security mechanisms is the file permission system. It’s the silent guardian that dictates who can read, who can write, and who can execute every single file and directory. While often taken for granted, a misunderstanding or misconfiguration of these permissions can be the single point of failure that leads to catastrophic data breaches, system compromise, and operational chaos. Recent Linux security news frequently highlights how seemingly minor permission errors can create major vulnerabilities.

This system, inherited from the early days of UNIX, is elegant in its simplicity yet powerful in its application. It forms the bedrock of Discretionary Access Control (DAC) in virtually every Linux distribution, including giants like Debian, Ubuntu, and the entire ecosystem of enterprise Linux. For system administrators, DevOps engineers, and even casual desktop users, a deep understanding of file permissions isn’t just a “nice-to-have” skill—it’s an absolute necessity for maintaining a secure and stable environment. This article will take you on a comprehensive journey from the basic building blocks of `rwx` to advanced concepts like special permissions and Access Control Lists (ACLs), providing practical examples and best practices to help you master this essential aspect of Linux administration.

The Bedrock of Linux Security: Understanding Core Permissions

At its heart, the standard Linux permission model is built on two core concepts: the types of permissions that can be granted and the entities to whom they can be granted. Mastering this duality is the first step toward effective system management.

The Triumvirate: Read, Write, and Execute (rwx)

Every file and directory has a set of flags that control access. These three primary permissions behave differently depending on whether they are applied to a file or a directory:

- Read (r):

- On a file: Allows the contents of the file to be viewed or copied.

- On a directory: Allows the names of the files and subdirectories within it to be listed (e.g., using `ls`).

- Write (w):

- On a file: Allows the contents of the file to be modified or truncated.

- On a directory: Allows files and subdirectories to be created, deleted, or renamed within the directory. Note that this permission on the directory is required to delete a file, not the write permission on the file itself.

- Execute (x):

- On a file: Allows the file to be run as a program or script.

- On a directory: Allows the user to enter (i.e., `cd` into) the directory and access its contents. Without execute permission on a directory, even with read permission, you cannot access the files inside.

The Three Tiers: User, Group, and Other (ugo)

These `rwx` permissions are assigned to three distinct classes of users:

- User (u): The owner of the file or directory.

- Group (g): The group that is associated with the file or directory. This allows for a simple form of role-based access for multiple users.

- Other (o): Every other user on the system who is not the owner and is not a member of the group.

Decoding the `ls -l` Output

The `ls -l` command is your primary tool for viewing permissions. The output might look cryptic at first, but it’s logically structured. The first ten characters represent the file type and its permissions.

$ ls -l /bin/bash

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 1233848 Mar 22 10:45 /bin/bashLet’s break down that first part, `-rwxr-xr-x`:

- Character 1: File type (`-` for a regular file, `d` for a directory, `l` for a symbolic link, etc.).

- Characters 2-4: Permissions for the User (owner). Here, `rwx` means the owner (root) can read, write, and execute the file.

- Characters 5-7: Permissions for the Group. Here, `r-x` means members of the group (root) can read and execute, but not write.

- Characters 8-10: Permissions for Other. Here, `r-x` means everyone else can also read and execute the file.

Practical Application: Managing Permissions with `chmod`, `chown`, and `chgrp`

Understanding permissions is one thing; managing them is another. Linux provides a suite of powerful command-line tools for this purpose, essential for anyone following Linux administration news or working with systems like CentOS, Rocky Linux, or AlmaLinux.

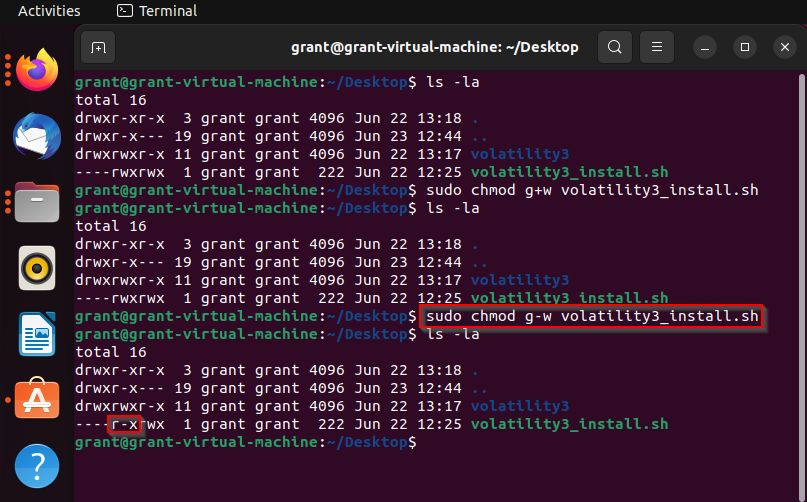

Changing Modes with `chmod`

The `chmod` (change mode) command is used to modify file and directory permissions. It can be used in two primary ways: symbolic and octal notation.

Symbolic Notation is more intuitive and descriptive. You specify which class (`u`, `g`, `o`, `a` for all), an operator (`+` to add, `-` to remove, `=` to set exactly), and which permission (`r`, `w`, `x`).

# Create a sample file and directory

touch report.txt

mkdir project_files

# Set initial permissions

# report.txt: User can read/write, Group can read, Others have no access

chmod u=rw,g=r,o= report.txt

# project_files: User can rwx, Group can rx, Others have no access

chmod u=rwx,g=rx,o= project_files

# Add execute permission for the user on a script

chmod u+x my_script.sh

# Remove write permission for the group on a directory

chmod g-w project_files

# Verify changes

ls -lOctal (Numeric) Notation is faster for setting all permissions at once and is commonly seen in scripts and automation tools like Ansible. Each permission is assigned a numeric value: `r=4`, `w=2`, `x=1`. These are added together for each class (user, group, other) to form a three-digit number.

- `7` = `4+2+1` = `rwx`

- `6` = `4+2` = `rw-`

- `5` = `4+1` = `r-x`

- `4` = `4` = `r–`

- `0` = `—` = No permissions

Common examples include `755` for executable scripts and directories (`rwxr-xr-x`) and `644` for regular files (`rw-r–r–`).

Changing Ownership with `chown` and `chgrp`

Sometimes you need to change who owns a file. The `chown` (change owner) command changes the user owner, while `chgrp` (change group) changes the group owner. The `chown` command can conveniently change both at once using a `user:group` syntax. These commands typically require superuser privileges (`sudo`).

# Create a new configuration file

sudo touch /etc/nginx/sites-available/myapp.conf

# Initially, it's owned by root:root

ls -l /etc/nginx/sites-available/myapp.conf

# Change the owner to 'www-data' and the group to 'webadmins'

sudo chown www-data:webadmins /etc/nginx/sites-available/myapp.conf

# Set permissions so the owner can read/write, group can read, and others nothing

sudo chmod 640 /etc/nginx/sites-available/myapp.conf

# Verify all changes

ls -l /etc/nginx/sites-available/myapp.confBeyond the Basics: Special Permissions and Access Control Lists (ACLs)

While the `ugo` model covers most use cases, Linux provides more advanced mechanisms for fine-grained control, which are crucial for complex multi-user environments and a frequent topic in Linux server news.

The Special Trio: SUID, SGID, and the Sticky Bit

These special permissions modify the standard behavior of executables and directories.

- SUID (Set User ID): When set on an executable file, it allows the user who runs the file to assume the identity of the file’s owner during execution. The classic example is the `/usr/bin/passwd` command. It is owned by `root` and has the SUID bit set, allowing a regular user to run it and modify the protected `/etc/shadow` file. In `ls -l`, this appears as an `s` in the user’s execute permission slot (`-rwsr-xr-x`). Misused SUID binaries are a severe security risk.

- SGID (Set Group ID): When set on an executable, it works like SUID but for the group owner. More usefully, when set on a directory, any new file or subdirectory created within it will automatically inherit the group ownership of the parent directory. This is invaluable for shared project folders. It appears as an `s` in the group’s execute slot (`drwxr-sr-x`).

- Sticky Bit (t): When set on a directory, it prevents users from deleting or renaming files they do not own, even if they have write permission to the directory. This is used on world-writable directories like `/tmp` and `/var/tmp` to prevent one user from deleting another’s temporary files. It appears as a `t` in the other’s execute slot (`drwxrwxrwt`).

Granular Control with Access Control Lists (ACLs)

What if you need to give one specific user, who isn’t the owner and isn’t in the group, write access to a file? The standard `ugo` model fails here. This is where ACLs come in. Supported by modern filesystems like ext4, Btrfs, and ZFS, ACLs allow you to add permissions for specific users and groups beyond the primary three. The `getfacl` and `setfacl` commands are used to manage them.

# Assume we have a shared directory for a project

sudo mkdir /srv/data/project_x

sudo chown admin:developers /srv/data/project_x

sudo chmod 770 /srv/data/project_x

# Now, we need to grant a temporary contractor, 'bob', read/write access

# The standard model can't do this without adding bob to the 'developers' group

# Use setfacl to add a specific rule for user 'bob'

sudo setfacl -m u:bob:rwx /srv/data/project_x

# Use getfacl to view the permissions. Note the '+' at the end of the ls output

# indicating an ACL is present.

getfacl /srv/data/project_x

# Output will show the standard permissions plus the new entry for 'user:bob:rwx'

ls -ld /srv/data/project_x

# drwxrwx---+ 2 admin developers 4096 Oct 26 13:37 /srv/data/project_xBest Practices, Pitfalls, and Modern Tooling

Applying these concepts correctly is key to a robust security posture. Whether you’re managing a single Arch Linux desktop or a fleet of cloud servers, these principles are universal.

The Principle of Least Privilege

This is the golden rule: always grant the minimum level of permission required for a user or service to perform its function. Never use `chmod 777` as a lazy fix. A world-writable file or directory is an open invitation for malicious actors to place malware, alter scripts, or escalate privileges. Use the `find` command to audit your system for dangerously open permissions.

# Find all world-writable directories on the system

find / -type d -perm -002 -exec ls -ld {} \;

# Find all SUID executables owned by root for security review

find / -type f -perm -4000 -user root -exec ls -l {} \;Leveraging Modern Security Frameworks

Standard permissions are a form of Discretionary Access Control (DAC), meaning the owner controls access. For higher security, distributions like those in the Red Hat news sphere (RHEL, Fedora, CentOS) and many others like Debian and Ubuntu heavily utilize Mandatory Access Control (MAC) systems like SELinux and AppArmor. These frameworks create system-wide policies that can override standard permissions, providing an additional, powerful layer of defense by confining processes to only the resources they are explicitly allowed to access.

Automation and Configuration Management

In modern DevOps and cloud environments, manually setting permissions is inefficient and error-prone. Tools central to Linux DevOps news, such as Ansible, Puppet, Chef, and SaltStack, are used to define and enforce file permissions as code. This ensures consistency, prevents configuration drift, and makes your infrastructure’s security posture auditable and repeatable. This is especially critical in containerized workflows with Docker, Podman, and Kubernetes, where base image permissions are a key security concern.

Conclusion: The Vigilant Administrator’s First Line of Defense

Linux file permissions are far more than a trivial administrative task; they are a fundamental pillar of system security and integrity. From the basic `rwx` triplets applied to user, group, and other, to the nuanced power of SUID/SGID bits and the granular control offered by ACLs, these tools provide a robust framework for safeguarding data. By embracing the principle of least privilege, regularly auditing your systems, and leveraging modern automation and security frameworks, you can transform this simple mechanism into a formidable defense.

For anyone serious about a career in Linux administration, cybersecurity, or development, mastering file permissions is non-negotiable. It’s a foundational skill that remains as relevant today with complex Kubernetes Linux news and cloud deployments as it was in the early days of UNIX. Take the time to review your own systems, question overly permissive settings, and build security from the ground up—one correctly set file at a time.