Navigating GRUB Updates: Why Your Linux System Might Fail to Boot and How to Prevent It

In the dynamic world of Linux, system updates are a routine part of life, bringing security patches, new features, and performance improvements. We diligently run apt upgrade, dnf update, or pacman -Syu, trusting our package managers to handle the complexities. However, one critical component often requires manual intervention that, if missed, can lead to a system that refuses to boot: the GRand Unified Bootloader, or GRUB. Recent discussions across various Linux communities, from Gentoo news forums to Arch Linux news feeds, have highlighted a recurring issue where users update their system, including the GRUB package, only to be met with a dreaded grub rescue> prompt on the next reboot. This isn’t a bug; it’s a fundamental aspect of how bootloaders work.

This comprehensive article delves into the intricacies of GRUB updates, explaining why simply updating the package isn’t enough. We’ll explore the essential grub-install command, provide practical examples for both legacy BIOS and modern UEFI systems, and outline best practices to ensure your system remains bootable and robust. Whether you’re a seasoned system administrator managing a fleet of Linux servers or a desktop user running Ubuntu, Fedora, or Manjaro, understanding this process is crucial for maintaining a healthy Linux installation.

The Two Faces of GRUB: The Package vs. The Boot Sector

The core of the confusion surrounding GRUB updates stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of where GRUB lives and operates. It exists in two distinct places: as a software package managed by your distribution’s package manager and as executable code written to a special, low-level area of your storage device.

1. The GRUB Package

When you run a system update, your package manager (like apt, yum, dnf, pacman, or portage) downloads and installs the latest version of the GRUB package. This package contains several key components that reside within your root filesystem, typically in directories like:

/usr/bin/and/usr/sbin/: Executable utilities likegrub-install,grub-mkconfig, andgrub-probe./etc/grub.d/: A directory containing scripts thatgrub-mkconfiguses to generate the main configuration file./etc/default/grub: The primary user-facing configuration file where you set kernel parameters, timeouts, and themes./boot/grub/: Contains modules, fonts, themes, and the finalgrub.cfgconfiguration file.

Updating this package gives you new tools, bug fixes for the configuration generator, and updated modules. However, it does not automatically update the code that actually starts the boot process.

2. The Bootloader Code

This is the critical, low-level part of GRUB that executes before the Linux kernel is even loaded. Its location depends on your system’s firmware and partition scheme:

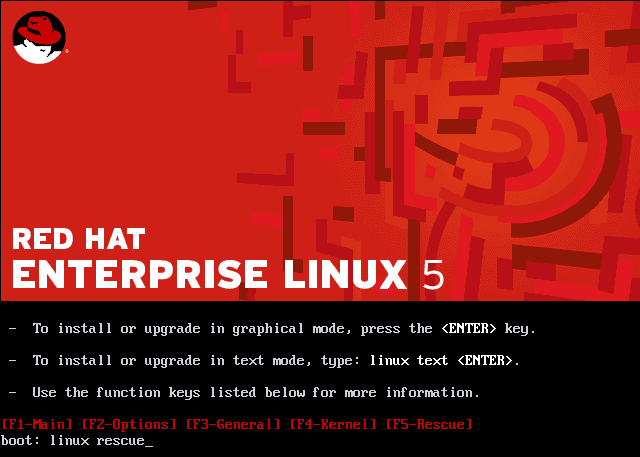

grub rescue screen – How to boot Red Hat Enterprise Linux to Rescue Mode for Data …

- Legacy BIOS/MBR: The initial stage of the bootloader is written to the first 512 bytes of the hard drive, known as the Master Boot Record (MBR). This tiny piece of code is responsible for loading the next stage of GRUB from the “post-MBR gap” or a specific partition.

- Modern UEFI: The bootloader is stored as an

.efifile (e.g.,grubx64.efi) on a dedicated, FAT32-formatted partition called the EFI System Partition (ESP), which is typically mounted at/boot/efi. The firmware is configured to load this file on startup.

When a significant GRUB update is released—especially one that patches a security vulnerability like the “BootHole” family of exploits—the new, patched bootloader code from the updated package must be manually written to the MBR or the ESP. If you fail to do this, you create a dangerous mismatch: the updated GRUB modules and configuration in /boot/grub/ may be incompatible with the old, vulnerable bootloader code still residing in the boot sector. This mismatch is a primary cause of boot failures after an update.

# Check the version of the installed GRUB package (Debian/Ubuntu)

dpkg -l | grep grub-pc-bin

# Check the version of the installed GRUB package (Fedora/RHEL)

rpm -q grub2-common

# Now, check the version reported by the *actual* bootloader

# Reboot and look at the version number displayed on the GRUB menu,

# or run this command, which might show the installed version.

# Note: This is not always 100% reliable.

sudo grub-install --versionThe `grub-install` Command: Bridging the Gap

The command that synchronizes the boot sector code with the updated package files is grub-install. This utility takes the core bootloader images provided by the new package and correctly installs them to the target device’s MBR or ESP. Running this command is the missing step that many users overlook, leading to post-update boot issues. The exact syntax varies slightly between BIOS and UEFI systems.

Installation on a Legacy BIOS/MBR System

On a traditional BIOS system, you install GRUB directly to the disk device itself (e.g., /dev/sda, /dev/nvme0n1), not a partition. The command finds the MBR of that device and overwrites it with the new boot code.

# Identify your boot disk. Use lsblk to be sure.

lsblk

# Example output:

# NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINTS

# sda 8:0 0 238.5G 0 disk

# ├─sda1 8:1 0 512M 0 part /boot/efi

# └─sda2 8:2 0 238G 0 part /

# For a BIOS system, the target is the disk, NOT a partition.

# WARNING: Ensure you have the correct device name.

# Using the wrong one can make another OS unbootable.

sudo grub-install /dev/sda

# The command should output something like:

# Installing for i386-pc platform.

# Installation finished. No error reported.Installation on a Modern UEFI System

For UEFI systems, the process is safer and more standardized. You don’t target the raw disk. Instead, you tell grub-install where your EFI System Partition (ESP) is mounted. This partition is where the bootloader EFI application will be placed. Most distributions, including those following modern systemd news and boot standards, mount the ESP at /boot/efi.

# On most UEFI systems, no device argument is needed.

# The command uses efibootmgr to find the ESP automatically.

sudo grub-install --target=x86_64-efi --efi-directory=/boot/efi --bootloader-id=GRUB

# Breakdown of the options:

# --target=x86_64-efi: Specifies the platform is 64-bit UEFI.

# --efi-directory=/boot/efi: Points to the mount point of your ESP.

# --bootloader-id=GRUB: Sets the name of the boot entry in the UEFI firmware menu.

# This helps distinguish it from Windows Boot Manager or others.

# The command should output:

# Installing for x86_64-efi platform.

# Installation finished. No error reported.After running grub-install, the final step is to regenerate the main configuration file, grub.cfg, to ensure it detects all your installed kernels and operating systems.

Generating Configuration and Advanced Scenarios

Installing the bootloader code is only half the battle. That code needs a configuration file to tell it what to do—which kernels to list, what root filesystem to use, and what kernel parameters to apply. This is handled by grub-mkconfig.

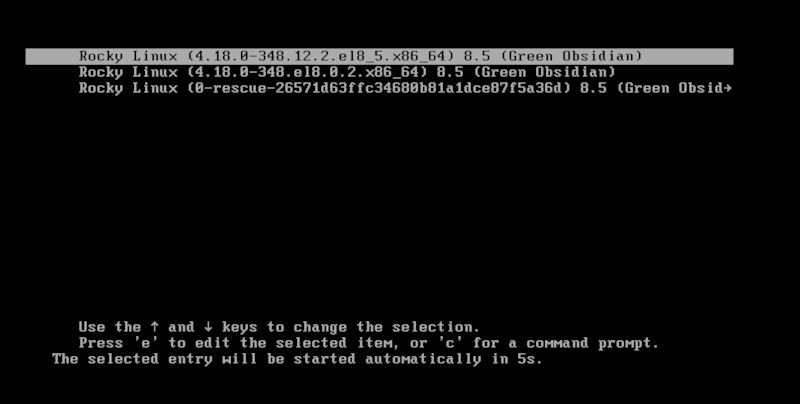

grub rescue screen – How to Boot RHEL 8 / CentOS 8 in Rescue Mode

Regenerating grub.cfg

Most distributions provide a simple wrapper script for this command. On Debian, Ubuntu, Linux Mint, and their derivatives, you use update-grub. On other systems like Fedora, Arch Linux, and Gentoo, you call grub-mkconfig directly, redirecting its output to the correct location.

# On Debian-based systems (Ubuntu, Mint, Pop!_OS)

sudo update-grub

# On Fedora, RHEL, CentOS, Arch Linux, Gentoo

# The output path may vary slightly based on BIOS vs UEFI.

# Check your distribution's documentation if unsure.

sudo grub-mkconfig -o /boot/grub/grub.cfgThis command scans your system for Linux kernels and, if configured, other operating systems, then builds a fresh grub.cfg file based on the templates in /etc/grub.d/ and settings in /etc/default/grub.

Troubleshooting with `efibootmgr`

On UEFI systems, a common issue is a misconfigured boot order in the firmware. The efibootmgr utility is an indispensable tool for inspecting and managing UEFI boot entries directly from Linux. After running grub-install, you can use it to verify that your new entry was created and is at the top of the boot order.

grub rescue screen – How to Boot RHEL 8 / CentOS 8 in Rescue Mode

# List current UEFI boot entries and the boot order

sudo efibootmgr -v

# Example output:

# BootCurrent: 0000

# Timeout: 1 seconds

# BootOrder: 0000,0001

# Boot0000* GRUB HD(1,GPT, ... )/File(\EFI\GRUB\grubx64.efi)

# Boot0001* Windows Boot Manager HD(1,GPT, ... )/File(\EFI\Microsoft\Boot\bootmgfw.efi)

# If 'GRUB' (Boot0000) is not first in BootOrder, you can change it:

sudo efibootmgr -o 0000,0001Best Practices for a Bulletproof Boot Process

To avoid being caught off guard by GRUB updates and other potential boot issues, adopt these best practices as part of your regular Linux administration workflow.

- Read Package Manager News: Distributions like Gentoo (via

portage news) and Arch Linux explicitly warn users when manual intervention is required for a package. Always read these messages before proceeding with major updates. - Understand Your System: Know whether your system uses BIOS or UEFI. This knowledge is critical for choosing the correct

grub-installcommand. You can check for the existence of the/sys/firmware/efidirectory; if it exists, you are on a UEFI system. - Create Backups and Snapshots: Before any major system upgrade, especially one involving core components like the kernel, glibc, or GRUB, create a system snapshot. Filesystem-level tools like Btrfs snapshots or ZFS snapshots are ideal. Alternatively, tools like Timeshift provide an excellent, user-friendly way to create restorable system backups.

- Keep a Live USB Handy: Always have a bootable Linux Live USB for your distribution of choice. If your system fails to boot, you can use the live environment to

chrootinto your installed system, run the necessarygrub-installandgrub-mkconfigcommands, and recover your system. - Run the Two-Step Process: Make it a habit. After any update that includes

grub, perform the two-step fix: first, rungrub-installto update the boot sector code, and second, runupdate-gruborgrub-mkconfigto regenerate the configuration. This proactive approach prevents nearly all GRUB-related boot failures.

Conclusion: Proactive Management is Key

The GRUB bootloader is a foundational piece of the entire Linux ecosystem, yet its update process remains a common stumbling block. The key takeaway is that the GRUB software on your filesystem and the GRUB code in your boot sector are two separate entities that must be kept in sync manually. A package manager update only handles the first part; it is your responsibility as the system administrator to handle the second.

By understanding this distinction and integrating the grub-install and grub-mkconfig commands into your post-update checklist, you can transform a potential system-breaking event into a routine maintenance task. Staying informed through Linux news channels, maintaining backups, and keeping recovery media on hand will ensure that your journey through the ever-evolving world of Linux remains smooth, stable, and, most importantly, bootable.