Deconstructing the KSMBD 0-Click RCE: A Deep Dive into a Critical Linux Kernel Vulnerability

In the ever-evolving landscape of cybersecurity, vulnerabilities within the core of an operating system represent the most critical threats. Recently, the Linux community has been closely monitoring a series of vulnerabilities discovered in KSMBD, an in-kernel SMB server module. These flaws can be chained together to achieve a “0-click” Remote Code Execution (RCE) exploit, a nightmare scenario for system administrators. A 0-click exploit requires no user interaction, allowing an attacker to compromise a system simply by sending specially crafted network packets to an exposed service. When this occurs at the kernel level, the attacker gains the highest level of privilege, effectively taking complete control of the machine.

This article provides a comprehensive technical breakdown of this significant Linux security news. We will explore what KSMBD is, dissect the anatomy of this type of vulnerability, and provide actionable, practical steps for mitigation, detection, and hardening. Understanding the mechanics behind such a powerful exploit is crucial for administrators managing everything from small home servers to large enterprise deployments running Debian, Ubuntu, Red Hat, or any other major Linux distribution. This is a critical development in Linux kernel news and reinforces the need for constant vigilance in system administration.

Understanding the Attack Surface: KSMBD and 0-Click Exploits

To fully grasp the severity of this vulnerability, we first need to understand the components involved. The exploit targets a specific module within the Linux kernel that handles a common networking protocol.

What is SMB and KSMBD?

The Server Message Block (SMB) protocol, also known as Common Internet File System (CIFS), is a network file-sharing protocol that allows applications on a computer to read and write to files and to request services from server programs in a computer network. It’s the native file-sharing protocol in Windows and is widely supported on other operating systems, including Linux, through the popular user-space daemon, Samba.

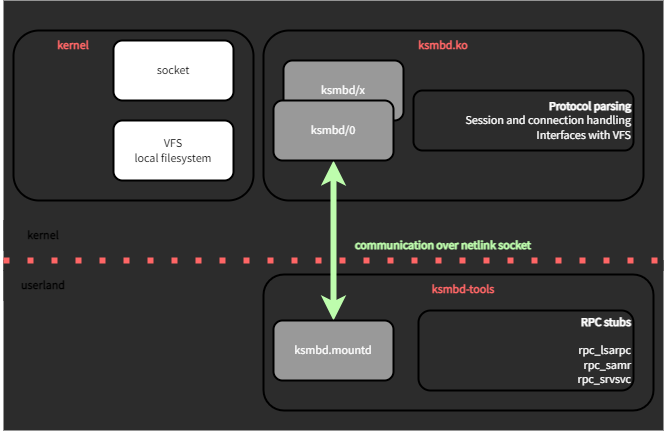

To improve performance, the Linux kernel introduced KSMBD (Kernel SMB Daemon) starting in kernel version 5.15. Unlike the traditional Samba suite, which runs in user space, KSMBD implements the SMB3 protocol directly within the kernel. This in-kernel approach reduces context switching and data copying between kernel space and user space, offering significant performance gains for file-serving operations. However, placing complex protocol parsing logic directly into the kernel also elevates the risk; a bug in this code can lead to a direct compromise of the entire system, a key piece of recent Linux security news.

The Anatomy of a 0-Click Kernel RCE

A “0-Click” Remote Code Execution exploit is the holy grail for attackers. It means an adversary can execute arbitrary code on a target machine without any action from a user. There’s no need to trick someone into clicking a malicious link, opening a tainted file, or running a compromised executable. The attack is silent, remote, and devastating.

When this RCE occurs at the kernel level, the consequences are catastrophic. The attacker’s code runs with the highest possible privileges (ring 0), bypassing all security mechanisms like sandboxing, user permissions, and even Mandatory Access Control systems like SELinux or AppArmor in many cases. The attacker gains full control to read any file, install rootkits, pivot to other machines on the network, or exfiltrate sensitive data.

The first step in assessing your risk is to determine if your system is running the vulnerable module. You can check your kernel version and see if the ksmbd module is loaded.

# Check the current Linux kernel version

uname -r

# Check if the ksmbd kernel module is loaded

lsmod | grep ksmbd

# If the command returns output, the module is active.

# Example output:

# ksmbd 647168 0

# cifs 184320 1 ksmbd

# libarc4 16384 1 cifsDissecting the KSMBD Vulnerability Chain

The recent exploit isn’t based on a single bug but rather a chain of vulnerabilities. Attackers often combine multiple, less severe bugs to achieve a powerful outcome like RCE. In the case of KSMBD, the reported vulnerabilities included flaws like use-after-free and out-of-bounds reads/writes within the processing of specific SMB commands. An unauthenticated attacker on the same local network can send a malicious SMB packet to trigger this chain.

The Exploit Pathway

- Reconnaissance: The attacker first identifies potential targets by scanning the network for systems with an open SMB port (typically TCP port 445). Tools like Nmap are commonly used for this discovery phase.

- Triggering the Bug: The attacker sends a specially crafted SMB packet to the target’s KSMBD service. This packet is designed to exploit a specific flaw in how KSMBD parses a command, such as `SMB2_TREE_CONNECT`.

- Memory Corruption: The initial bug, perhaps an out-of-bounds write, allows the attacker to corrupt a small, controlled portion of the kernel’s memory. This is the foothold.

- Privilege Escalation: By chaining this with other vulnerabilities, such as a use-after-free bug, the attacker can leverage the initial memory corruption to overwrite function pointers or other critical data structures in the kernel. This allows them to redirect the kernel’s execution flow to their own malicious code (shellcode) injected into memory.

- Execution: The kernel, now tricked, executes the attacker’s shellcode with full kernel privileges, leading to a complete system compromise.

Administrators can perform basic reconnaissance on their own networks to identify systems running SMB services. This is a crucial step in understanding your attack surface.

# Use nmap to scan a specific IP or subnet for open SMB ports

# The -sV flag attempts to determine the version of the service

# The --script smb-os-discovery tries to gather OS information via SMB

nmap -p 445 -sV --script smb-os-discovery 192.168.1.0/24While we won’t show the actual exploit code, understanding the protocol interaction is useful. Python libraries like impacket are powerful tools for security researchers to craft and send custom network packets for protocols like SMB, which is how such vulnerabilities are often discovered and demonstrated.

# CONCEPTUAL EXAMPLE - NOT AN EXPLOIT

# This script demonstrates using impacket to connect to an SMB server.

# Researchers would modify this logic to send malformed data.

from impacket.smbconnection import SMBConnection

from impacket.smb3 import SMB2_TREE_CONNECT

# Target server IP address

target_ip = '192.168.1.100'

share_name = 'IPC$'

try:

# Establish a connection (can be anonymous)

conn = SMBConnection(target_ip, target_ip, sess_port=445)

# In a real exploit, an attacker would send a malformed

# TreeConnect request here instead of a legitimate one.

# For example, with an invalid path or oversized buffer.

conn.connectTree(share_name)

print(f"[+] Successfully connected to share: {share_name} on {target_ip}")

# ... further interaction would occur here ...

conn.logoff()

print("[-] Connection closed.")

except Exception as e:

print(f"[!] Failed to connect: {e}")Practical Mitigation and System Hardening

Protecting your systems requires a multi-layered approach, often referred to as “defense in depth.” While patching is the ultimate solution, other measures can prevent exploitation or limit the blast radius if a compromise occurs.

1. Patch Your Kernel Immediately

The most critical step is to update your Linux kernel to a patched version. This is paramount Linux administration news for all users. Major distributions like Ubuntu, Fedora, Arch Linux, and Red Hat have already released updates. Check your distribution’s package manager for the latest kernel and reboot your system to apply it.

- Debian/Ubuntu:

sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade - RHEL/Fedora/CentOS:

sudo dnf updateorsudo yum update - Arch Linux:

sudo pacman -Syu

2. Network-Level Hardening with Firewalls

If you do not need to expose SMB/CIFS services to the internet or untrusted networks, you should block TCP port 445 at your network perimeter. For internal networks, restrict access to only the specific clients that require it. This is a fundamental principle of Linux firewall news and best practices.

Here is an example using nftables, the modern replacement for iptables, to block incoming KSMBD traffic from an untrusted network interface.

# Example using nftables to block SMB traffic on an external interface (e.g., eth0)

# Create a new table for our rules

sudo nft add table inet filter

# Create a chain for incoming traffic

sudo nft add chain inet filter input { type filter hook input priority 0 \; }

# Add a rule to drop all new connections to port 445 on the 'eth0' interface

sudo nft add rule inet filter input iifname "eth0" tcp dport 445 drop

# To save the ruleset so it persists after reboot (Debian/Ubuntu)

# sudo apt install nftables

# sudo systemctl enable nftables

# sudo nft list ruleset > /etc/nftables.conf3. Disable KSMBD if Not in Use

The principle of least privilege dictates that you should not run services you don’t need. If your server does not require high-performance SMB file sharing, or if you are using the traditional user-space Samba daemon, you should disable KSMBD entirely. This completely removes the vulnerable code from your attack surface.

You can disable the kernel module by blacklisting it. This prevents it from being loaded automatically on boot.

# Create a modprobe configuration file to blacklist the ksmbd module

echo "blacklist ksmbd" | sudo tee /etc/modprobe.d/ksmbd-blacklist.conf

# You may need to update your initramfs for the change to take full effect on boot

# For Debian/Ubuntu:

sudo update-initramfs -u

# For RHEL/Fedora:

sudo dracut -f -v

# After creating the file and rebooting, verify the module is not loaded

lsmod | grep ksmbdLong-Term Best Practices for Kernel Security

This KSMBD vulnerability serves as a stark reminder of the importance of robust security practices. While immediate mitigation is crucial, adopting a long-term strategy is essential for protecting against future threats.

Embrace Automated Patch Management

Manually updating systems is prone to error and delay. For critical infrastructure, especially servers, implement an automated patch management solution. Tools like unattended-upgrades on Debian/Ubuntu systems or satellite management systems for enterprise distros can ensure that critical security patches are applied as soon as they become available. This is vital for keeping up with Linux kernel news and security advisories.

Implement Defense in Depth

Do not rely on a single layer of security. A defense-in-depth strategy involves multiple, redundant security controls:

- Network Firewalls: As discussed, restrict traffic at the network edge and on the host itself.

- Mandatory Access Control (MAC): Use SELinux (on RHEL/Fedora) or AppArmor (on Debian/Ubuntu/SUSE) to confine services. A well-crafted MAC policy could potentially prevent a compromised kernel-level service from performing certain malicious actions, such as executing arbitrary code from a non-executable memory region.

- Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS/IPS): Monitor network traffic for signatures of known exploits or anomalous behavior.

- Regular Audits: Periodically audit your systems for open ports, unnecessary services, and misconfigurations.

Monitor System Logs and Network Traffic

Proactive monitoring can help you detect an attack in progress. Use tools like journalctl to monitor kernel logs for unusual messages (e.g., kernel panics or oopses), which could indicate a failed exploit attempt. Monitor network traffic for unusual spikes or connections to port 445 from unexpected sources. This is a core tenet of modern Linux observability and incident response.

Conclusion: A Call for Vigilance

The 0-click RCE vulnerability in the Linux kernel’s KSMBD module is a serious threat that highlights the inherent risks of adding complex, network-facing services directly into the kernel. While in-kernel modules can offer performance benefits, they also present a highly privileged and attractive target for attackers. This event is a critical piece of Linux server news that should prompt immediate action from administrators everywhere.

The key takeaways are clear and actionable. First, patch your systems immediately to eliminate the vulnerability. Second, adopt a proactive security posture by hardening your network with firewalls and disabling any services, like KSMBD, that are not strictly necessary for your operations. Finally, embrace a long-term, defense-in-depth strategy that includes automated patching, mandatory access control, and vigilant monitoring. In the world of Linux security, staying informed and acting decisively is our best defense against the next inevitable threat.