Fortifying Your DevOps Core: A Deep Dive into GitLab DoS and SSRF Vulnerabilities

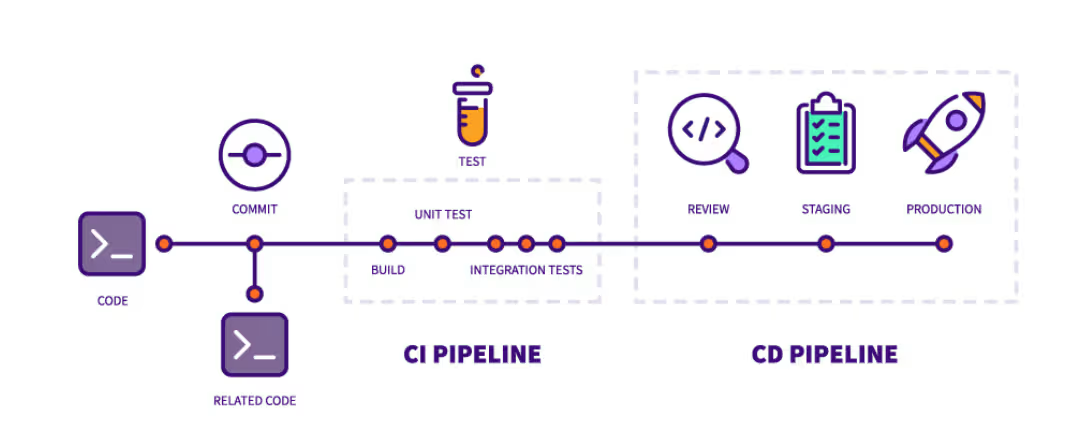

In the world of modern software development, GitLab stands as a cornerstone of the DevOps lifecycle. From small teams to large enterprises, its comprehensive suite of tools for version control, CI/CD, and project management is often the engine driving innovation. Running predominantly on Linux-based infrastructure, from popular distributions like Ubuntu and Debian to enterprise-grade systems like Red Hat and Rocky Linux, GitLab’s stability and security are paramount. The latest GitLab news regarding security patches serves as a critical reminder that even the most robust platforms require constant vigilance.

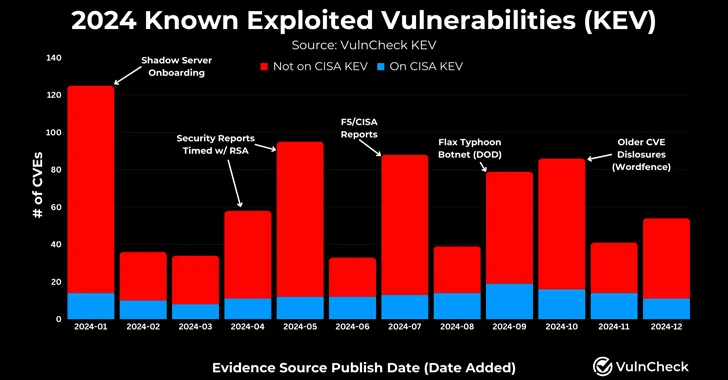

Recent advisories have highlighted vulnerabilities that could lead to serious security incidents, specifically Denial of Service (DoS) and Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) attacks. These are not trivial threats; a successful exploit can bring development pipelines to a grinding halt, expose sensitive internal infrastructure, and erode trust in your security posture. This article provides a comprehensive technical breakdown of these vulnerabilities, explores how they manifest within GitLab, and offers actionable strategies and best practices for system administrators and DevOps engineers to fortify their instances. Understanding these issues is essential for anyone following Linux security news and managing critical infrastructure.

Understanding the Threats: A Primer on DoS and SSRF Attacks

Before diving into GitLab-specific scenarios, it’s crucial to understand the fundamental mechanics of Denial of Service and Server-Side Request Forgery. These attack vectors target different aspects of an application but can be equally devastating.

Denial of Service (DoS): The Threat of Exhaustion

A Denial of Service attack aims to make a machine or network resource unavailable to its intended users. Rather than stealing data, its goal is disruption. This is often achieved by overwhelming the target system with a flood of requests or by sending it data that triggers a resource-intensive operation, causing it to crash or become unresponsive. In the context of a complex application like GitLab, which relies on numerous services (Puma, Sidekiq, Gitaly, PostgreSQL), a DoS vulnerability in one component can cause a cascading failure across the entire platform. This directly impacts everything from Git Linux news and repository access to the entire Linux CI/CD pipeline.

Imagine a feature that processes user-submitted data. An attacker could craft a “computational bomb”—a small input that triggers an extremely complex, long-running process. For example, a script that calculates Fibonacci numbers recursively is a classic example of an operation with exponential time complexity.

# WARNING: Educational purposes only. This demonstrates a resource-intensive task.

# Running this with a large number can freeze the system.

def recursive_fibonacci(n):

"""

A deliberately inefficient function to demonstrate computational complexity.

"""

if n <= 1:

return n

else:

return recursive_fibonacci(n-1) + recursive_fibonacci(n-2)

def process_request(user_input):

"""

Simulates a server endpoint processing user input.

"""

try:

number = int(user_input)

# An attacker could provide a relatively small number like 40,

# which would trigger a massive number of recursive calls.

if 0 < number < 45: # A sane upper limit is necessary

result = recursive_fibonacci(number)

print(f"Fibonacci({number}) = {result}")

else:

print("Input out of a safe range.")

except ValueError:

print("Invalid input.")

# Simulating an attacker's input that could cause a DoS

# On a server, this input would come from an HTTP request.

process_request("40")If a GitLab feature (like rendering a complex Markdown file or parsing an issue import) contained a similar computational flaw, an attacker could repeatedly trigger it, consuming all available CPU resources and bringing the Linux server news for that day to a very unhappy conclusion.

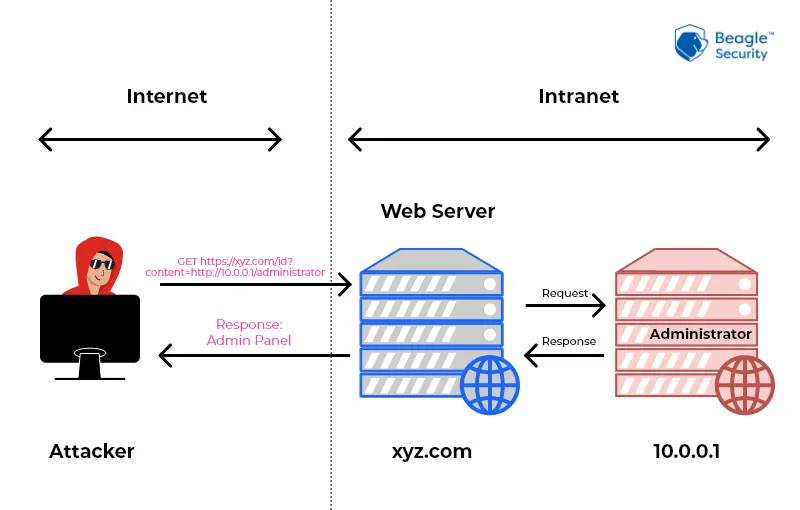

Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF): Turning the Server Against Itself

Server-Side Request Forgery is a more insidious vulnerability. It tricks a server-side application into making HTTP requests to an arbitrary domain chosen by the attacker. Because the request originates from the trusted server itself, it can bypass firewalls and access internal, non-public resources.

The consequences are severe. An attacker could:

- Scan the internal network for open ports and services.

- Access internal applications like admin panels, databases (PostgreSQL Linux news, Redis Linux news), or monitoring dashboards (Prometheus, Grafana).

- Query cloud metadata services on platforms like AWS, Azure, or Google Cloud to steal access credentials. The address

169.254.169.254is a notorious target in AWS Linux news security incidents. - Send requests to other internal services, potentially triggering actions or exfiltrating data.

A simple web application written in Python using Flask can illustrate this vulnerability. Imagine an endpoint designed to fetch an image from a URL provided by the user.

# WARNING: This code is deliberately vulnerable to SSRF. DO NOT USE IN PRODUCTION.

from flask import Flask, request

import requests

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/fetch-image')

def fetch_image():

image_url = request.args.get('url')

if not image_url:

return "Please provide a 'url' parameter.", 400

try:

# The vulnerability is here: the application blindly makes a request

# to any URL provided by the user.

response = requests.get(image_url, timeout=5)

# In a real app, it would return the image content.

# Here, we just return the status for demonstration.

return f"Fetched URL with status: {response.status_code}", 200

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

return f"Could not fetch URL: {e}", 500

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Running on 0.0.0.0 makes it accessible on the network

app.run(host='0.0.0.0', port=5000)

# Attacker could make a request like:

# http://your-server:5000/fetch-image?url=http://127.0.0.1:6379 (to probe for Redis)

# http://your-server:5000/fetch-image?url=http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/ (to probe AWS metadata)In GitLab, features like webhooks or project mirroring, which inherently need to make outbound requests, are potential candidates for SSRF if input validation is not perfectly implemented.

GitLab in the Crosshairs: How These Vulnerabilities Manifest

Understanding the theory is one thing; seeing how it applies to a real-world application like GitLab is another. These vulnerabilities often arise from the complex interplay of features designed to improve the Linux DevOps news experience.

Exploiting GitLab Features for Denial of Service

A DoS attack on GitLab might not involve a massive traffic flood. Instead, it can be a “low and slow” attack targeting a specific, resource-heavy feature. Potential vectors in GitLab could include:

- File Parsers: Features that parse uploaded files (e.g., project import/export, CI/CD artifact processing, Markdown rendering) can be targets. A maliciously crafted file, sometimes called a “zip bomb” or “billion laughs” XML entity attack, can cause the parser to consume excessive memory or CPU.

- Complex API Queries: A deeply nested or complex GraphQL API query could force the backend, often a PostgreSQL Linux news database, to perform an expensive join operation, slowing down the entire application for all users.

- Regex Processing: Some features may use Regular Expressions to validate input. A poorly written regex can be susceptible to ReDoS (Regular Expression Denial of Service), where a specially crafted string causes catastrophic backtracking and freezes the processing thread.

The impact is felt across the board. The GitLab web interface becomes unresponsive, Git operations via Linux SSH news or HTTPS time out, and critical GitLab CI news pipelines stall, halting deployments and developer productivity.

Uncovering SSRF Pathways in GitLab

GitLab’s extensive integration capabilities are a double-edged sword. Features that connect to external services are prime targets for SSRF. An attacker doesn’t need deep access; a low-privileged user account might be enough to exploit a vulnerable endpoint.

Common entry points include:

- Webhooks: If the URL validation for a project webhook is flawed, an attacker could configure it to point to an internal IP address. When a repository event (like a push) occurs, the GitLab server itself sends a POST request to the attacker’s specified internal target.

- Project Import from URL: The feature to import a repository from a URL could be tricked into connecting to internal services instead of a legitimate Git repository.

- Kubernetes Integration: The integration with Kubernetes clusters requires GitLab to communicate with the Kubernetes API server. A flaw in how this endpoint is configured or validated could potentially be leveraged for SSRF.

An attacker could use a simple curl command to test a hypothetical vulnerable webhook endpoint, demonstrating the ease of crafting such a payload.

# Example of an attacker's payload to test a webhook for SSRF

# This assumes the attacker has an account and an API token.

# The target_url is the malicious part, pointing to an internal service.

GITLAB_URL="https://gitlab.example.com"

PROJECT_ID="12345"

PRIVATE_TOKEN="your_private_api_token"

TARGET_URL="http://127.0.0.1:9090/api/v1/status/buildinfo" # Probing an internal Prometheus server

curl --request POST --header "PRIVATE-TOKEN: ${PRIVATE_TOKEN}" \

--header "Content-Type: application/json" \

--data '{

"url": "'"${TARGET_URL}"'",

"push_events": true,

"enable_ssl_verification": false

}' \

"${GITLAB_URL}/api/v4/projects/${PROJECT_ID}/hooks"

# If the webhook is created and later triggered, GitLab's server will make a request to the internal Prometheus instance.Proactive Defense: Detection and Mitigation Strategies

Securing your GitLab instance requires a multi-layered approach, combining timely updates, robust configuration, network controls, and diligent monitoring. This is a core tenet of modern Linux administration news and security.

Hardening Your GitLab Instance with Configuration

The first line of defense is always to keep your GitLab instance up to date. The GitLab team is proactive in patching vulnerabilities, and applying these updates is the single most effective mitigation. For Omnibus installations, this is as simple as running `sudo apt-get update && sudo apt-get install gitlab-ee` on Debian/Ubuntu systems or the `dnf` equivalent on Fedora/RHEL systems, reflecting the latest apt news and dnf news.

Beyond patching, you can harden your instance via the `gitlab.rb` configuration file. Implementing rate limiting is crucial for mitigating DoS attacks.

# Example /etc/gitlab/gitlab.rb configuration for rate limiting

# This helps protect against brute-force and certain DoS attacks.

# Enable Rack Attack middleware

gitlab_rails['rack_attack_git_basic_auth'] = {

'enabled' => true,

'ip_whitelist' => ["127.0.0.1", "192.168.1.0/24"],

'maxretry' => 10,

'findtime' => 60, # seconds

'bantime' => 3600 # seconds

}

# You can also set rate limits on specific API endpoints or user actions.

# See the official GitLab documentation for more advanced options.

# After changing this file, run `sudo gitlab-ctl reconfigure`.Managing this configuration using tools like Ansible news or Terraform Linux news ensures your security posture is automated, version-controlled, and consistently applied across all environments.

Network-Level and Application-Level Defenses

To combat SSRF, you must control the GitLab server’s outbound network traffic. Use a firewall like iptables news or its modern successor, nftables news, to create an egress policy that denies all outbound connections by default and only allows traffic to specific, required services (e.g., external package registries, object storage).

At the application level, proper URL validation is the key to preventing SSRF. A secure implementation should never blindly trust user input. Instead, it should parse the URL, resolve the IP address, and check it against an allow-list of permitted domains or a deny-list of private/reserved IP ranges.

# Example of a secure URL validation function in Python to prevent SSRF

import socket

from urllib.parse import urlparse

# List of private IP address blocks (as per RFC 1918 and others)

DENY_LIST_CIDRS = [

'127.0.0.0/8', '10.0.0.0/8', '172.16.0.0/12', '192.168.0.0/16',

'169.254.0.0/16', '0.0.0.0/8', '100.64.0.0/10', '192.0.0.0/24',

'192.0.2.0/24', '198.51.100.0/24', '203.0.113.0/24', '::1/128',

'fc00::/7' # Unique local addresses (IPv6)

]

def is_ip_in_cidrs(ip_str, cidrs):

"""Checks if an IP address belongs to any of the given CIDR blocks."""

from ipaddress import ip_address, ip_network

ip = ip_address(ip_str)

for cidr in cidrs:

if ip in ip_network(cidr):

return True

return False

def is_safe_url(url_string):

"""

Validates a URL to ensure it does not point to a private or reserved IP address.

"""

try:

parsed_url = urlparse(url_string)

# 1. Ensure the scheme is http or https

if parsed_url.scheme not in ['http', 'https']:

print(f"Error: Invalid scheme '{parsed_url.scheme}'")

return False

# 2. Get the IP address of the hostname

hostname = parsed_url.hostname

if not hostname:

print("Error: URL has no hostname.")

return False

# This DNS lookup is a crucial step

ip_address = socket.gethostbyname(hostname)

# 3. Check the resolved IP against the deny list

if is_ip_in_cidrs(ip_address, DENY_LIST_CIDRS):

print(f"Error: Resolved IP {ip_address} is in the deny list.")

return False

print(f"Success: URL {url_string} resolves to safe IP {ip_address}.")

return True

except (socket.gaierror, ValueError) as e:

print(f"Error: Could not process URL '{url_string}': {e}")

return False

# --- Test Cases ---

is_safe_url("https://google.com") # Should be True

is_safe_url("http://127.0.0.1/admin") # Should be False

is_safe_url("http://localhost:8000") # Should be False

is_safe_url("http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data") # Should be FalseIntegrating Security into the DevOps Lifecycle (DevSecOps)

A truly resilient system integrates security into every stage of the development process. This DevSecOps approach is essential for protecting complex platforms like GitLab.

Secure CI/CD Practices and Infrastructure

Your GitLab CI news pipeline is a powerful automation tool, but it’s also a potential attack surface. Ensure you are scanning your code, dependencies, and container images for vulnerabilities within the pipeline itself. Tools like Trivy, Grype, and GitLab’s own security scanners can be integrated to provide continuous security feedback.

Furthermore, secure your CI runners. Use ephemeral runners where possible, restrict their network access, and never store long-lived credentials directly in your `.gitlab-ci.yml` files. Instead, use GitLab’s built-in secret management capabilities. This is critical for protecting your Docker Linux news and Kubernetes Linux news environments.

Monitoring and Logging for Early Detection

You cannot defend against what you cannot see. Robust monitoring and logging are essential for detecting anomalies that could indicate an attack.

- Monitoring: Use tools like Prometheus news and Grafana news to monitor GitLab’s performance metrics. A sudden, sustained spike in CPU or memory usage on a specific node could be an early indicator of a DoS attack.

- Logging: Centralize and analyze GitLab’s logs from `/var/log/gitlab`. Look for unusual patterns, such as a high rate of failed requests in `production_json.log` or unexpected outbound connection attempts in the logs for Gitaly or Sidekiq. The ELK Stack news (Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana) or tools like Loki and Graylog are invaluable for this kind of analysis. On the host system, `journalctl` is your go-to command for inspecting service logs on any modern systemd news-based distribution.

Conclusion: A Call for Proactive Security

GitLab is an indispensable asset in the modern DevOps toolchain, but its power and complexity also make it a high-value target for attackers. The emergence of Denial of Service and Server-Side Request Forgery vulnerabilities is a stark reminder that security is not a one-time task but an ongoing process of vigilance, maintenance, and improvement.

The key takeaways for every administrator and DevOps professional are clear: prioritize timely updates, implement security-hardening configurations, control network egress, and establish comprehensive monitoring. By adopting a proactive security posture and integrating these best practices into your daily operations, you can significantly reduce your risk profile. Take the time today to review your GitLab instance, verify you are running the latest patched version, and assess your configurations against the strategies outlined here. In the ever-evolving landscape of Linux security news, a proactive defense is your greatest strength.