Mastering Linux File Permissions: A Comprehensive Guide to Securing Your System

The Unsung Hero of System Security: A Deep Dive into Linux File Permissions

In the world of Linux, from the sprawling server farms powering cloud infrastructure to the sleek desktops running Pop!_OS or Fedora, one fundamental concept stands as a primary gatekeeper of security: file permissions. While often taken for granted, this elegant system of rules dictates who can read, write, and execute files. Recent Linux security news frequently highlights how simple misconfigurations—a forgotten world-writable directory or an overly permissive script—can become the entry point for system compromise. Understanding and mastering these permissions is not just a task for seasoned system administrators; it’s an essential skill for any developer, DevOps engineer, or enthusiast serious about maintaining a secure and stable environment.

This comprehensive guide will take you on a journey from the foundational principles of the traditional Unix permission model to advanced techniques involving Access Control Lists (ACLs) and an introduction to Mandatory Access Control (MAC) systems like SELinux. We’ll explore practical examples, common pitfalls, and best practices that apply across the entire Linux ecosystem, whether you’re managing a Debian server, developing on Ubuntu, or exploring the latest Arch Linux news. By the end, you’ll have the knowledge to not only fix permission issues but to proactively design and enforce a robust security posture for your systems.

The Bedrock of Security: Understanding UGO and Basic Permissions

At its core, the standard Linux discretionary access control (DAC) model is built upon a simple yet powerful triad of identities and a corresponding set of permissions. This model has been a cornerstone of Unix-like operating systems for decades and remains critically relevant in all modern distributions, from RHEL to Slackware.

The “Who”: User, Group, and Other (UGO)

Every file and directory on a Linux filesystem has an owner and an associated group. The permission system uses this ownership to classify any process trying to access the file into one of three categories:

- User (u): The owner of the file.

- Group (g): Members of the group associated with the file.

- Other (o): Everyone else who is not the owner and not a member of the group.

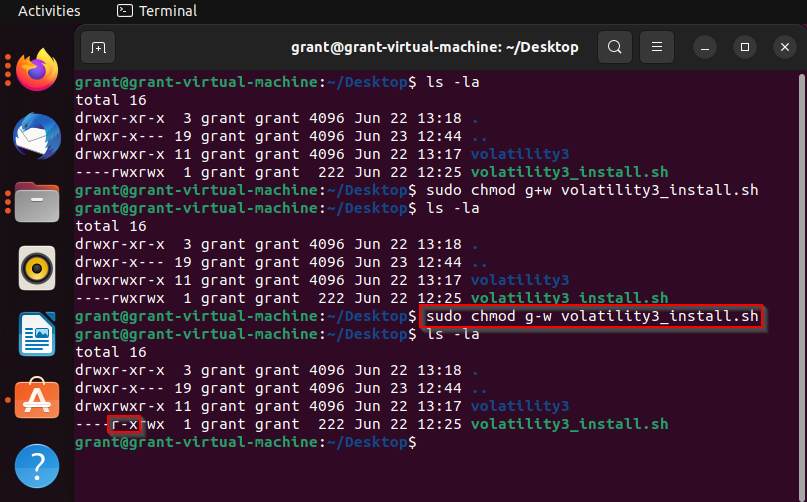

This UGO model provides a straightforward way to manage access rights. You can see this structure clearly when you run the ls -l command, a staple piece of Linux commands news for anyone working in the terminal.

$ ls -l my_script.sh

-rwxr-x--x 1 alice developers 1024 Oct 26 11:30 my_script.shLet’s break down that first column, -rwxr-x--x:

- The first character (

-) indicates the file type (-for a regular file,dfor a directory,lfor a symbolic link). - The next three characters (

rwx) are the permissions for the User (alice). - The following three (

r-x) are for the Group (developers). - The final three (

--x) are for Other.

The “What”: Read, Write, and Execute Permissions

Each of the UGO categories can be assigned three basic permissions:

- Read (r): Allows viewing the contents of a file or listing the contents of a directory.

- Write (w): Allows modifying or deleting a file. For a directory, it allows creating, deleting, and renaming files within it.

- Execute (x): Allows running the file as a program or script. For a directory, it allows entering (i.e., `cd`-ing into) it.

Decoding Permissions: Symbolic vs. Octal Notation

The chmod (change mode) command is used to modify these permissions. It accepts two common notations.

Symbolic notation is more intuitive. It uses letters (u, g, o, a for all) and operators (+ to add, – to remove, = to set) to modify permissions. This is excellent for making specific changes without recalculating everything.

Octal notation is a numeric shorthand where each permission is a value: read (4), write (2), and execute (1). These values are summed for each UGO category. For example, rwx is 4+2+1=7, and r-x is 4+0+1=5. This is the fastest way to set all permissions at once and is commonly seen in documentation and scripts.

# Using symbolic notation to make a script executable for the owner

$ chmod u+x my_script.sh

# Using symbolic notation to remove write permission for group and other

$ chmod go-w sensitive_data.txt

# Using octal notation to set permissions to rwxr-xr-x (755)

# This is a very common setting for executable scripts and directories

$ chmod 755 my_script.sh

# Using octal notation to set permissions to rw-r--r-- (644)

# This is a common, safe default for regular files

$ chmod 644 config.ymlBeyond the Basics: Special Permissions and Ownership

While UGO covers most daily use cases, Linux provides special permissions for more advanced scenarios. These are powerful tools but must be used with caution, as they have significant security implications. According to recent Linux server news, misconfigured special permissions are a classic privilege escalation vector.

Taking Control: The `chown` and `chgrp` Commands

Before diving into special permissions, it’s crucial to master ownership. The chown (change owner) and chgrp (change group) commands allow a privileged user (like root) to transfer ownership of files and directories. This is fundamental for Linux administration news topics, especially when managing user home directories or web server content.

Escalating Privileges Safely: The SUID and SGID Bits

The SUID (Set User ID) and SGID (Set Group ID) bits are special permissions that alter how a program is executed.

- SUID (Set User ID): When an executable file with the SUID bit is run, it executes with the permissions of the file owner, not the user who ran it. The classic example is the

passwdcommand, which needs to modify the protected/etc/shadowfile. It is owned by root with the SUID bit set, allowing a regular user to run it and change their own password securely. - SGID (Set Group ID): When set on an executable, it runs with the authority of the file’s group. When set on a directory, any new files or subdirectories created within it will inherit the group ownership of the parent directory, which is incredibly useful for collaborative project folders.

Protecting Shared Spaces: The Sticky Bit

The Sticky Bit is a permission that, when set on a directory, ensures that a user can only delete or rename files that they personally own within that directory, even if they have write permissions to the directory itself. This is why you can create files in /tmp but cannot delete files created by other users. It’s essential for securing publicly writable spaces.

# Find all SUID root executables on the system (a critical security audit step)

# This is a command every admin should know, often featured in RHCSA news and training

$ find / -user root -perm -4000 -exec ls -ldb {} \; 2>/dev/null

# Set the SGID bit on a shared project directory

# New files will now inherit the 'projects' group

$ sudo chmod g+s /srv/data/projects

# Check permissions on /tmp to see the sticky bit (indicated by the 't')

$ ls -ld /tmp

drwxrwxrwt 17 root root 20480 Oct 26 12:00 /tmpModern and Advanced Permission Controls

The traditional UGO model can be restrictive. What if you need to grant access to a single file to a user who isn’t the owner and doesn’t belong to the file’s group? This is where modern permission systems come into play, offering the granular control needed for complex environments discussed in Linux networking news and enterprise deployments.

When UGO Isn’t Enough: An Introduction to Access Control Lists (ACLs)

Access Control Lists (ACLs) extend the standard permission model. They allow you to define permissions for multiple specific users and groups on a single file or directory. Most modern Linux filesystems like ext4, Btrfs, and ZFS support ACLs, though they may need to be enabled. You can tell if a file has an ACL by the `+` sign at the end of the permission string in `ls -l` output.

Practical ACL Management with `getfacl` and `setfacl`

The `getfacl` and `setfacl` commands are the tools for managing these fine-grained permissions. They provide a powerful way to solve complex access problems without creating unnecessary user groups.

# First, view the existing ACL on a file (it will just show UGO by default)

$ getfacl report.docx

# file: report.docx

# owner: alice

# group: marketing

user::rw-

group::r--

other::---

# Now, use setfacl to grant read/write access to a specific user, 'bob'

$ setfacl -m u:bob:rw- report.docx

# View the ACL again to see the new entry

$ getfacl report.docx

# file: report.docx

# owner: alice

# group: marketing

user::rw-

user:bob:rw- # <-- Bob's specific permission

group::r--

mask::rw-

other::---

# The `ls -l` output now shows a '+'

$ ls -l report.docx

-rw-rw----+ 1 alice marketing 5120 Oct 26 12:15 report.docxThe Next Layer of Defense: Mandatory Access Control (MAC) with SELinux and AppArmor

While DAC (UGO and ACLs) is user-controlled, Mandatory Access Control (MAC) is a system-policy-based security model. Systems like SELinux (found in Fedora, CentOS, RHEL) and AppArmor (found in Ubuntu, Debian, SUSE) provide this. They operate on top of standard permissions, creating security contexts or profiles that confine processes to only the resources they absolutely need. For example, even if a web server process is compromised and running as root, SELinux news often reports how its context would prevent it from accessing user home directories or system binaries. This provides a powerful defense-in-depth strategy against zero-day vulnerabilities.

Auditing Your System for Permission Flaws

Regularly auditing your system for insecure permissions is a critical security practice. The `find` command is an indispensable tool for this task.

# Find all world-writable files on the system, excluding symlinks and sockets

$ find / -type f -perm -0002 ! -type l ! -type s -ls

# Find all files that are not owned by any user (orphaned files)

$ find / -nouser -o -nogroup

# Find all directories that are world-writable

$ find / -type d -perm -0002 -lsBest Practices and Proactive Security

Understanding the tools is only half the battle. Applying them wisely is what truly secures a system. This involves adhering to established principles and avoiding common mistakes.

The Principle of Least Privilege

This is the golden rule of security: any user, program, or process should only have the bare minimum permissions necessary to perform its function. Never grant `rwx` to “other” just to get something working quickly. Always start with the most restrictive permissions and open them up as needed.

Setting Sensible Defaults with `umask`

The `umask` (user mask) command sets the default permissions for newly created files and directories. It works by “masking off” permissions from the system defaults (666 for files, 777 for directories). A common and secure `umask` is `022`, which results in default permissions of 644 for files and 755 for directories. An even more private `umask` of `077` would result in 600 for files and 700 for directories, ensuring new files are private by default.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- The `chmod 777` Trap: Using `chmod -R 777` is a notorious anti-pattern. It makes every file and subdirectory readable, writable, and executable by everyone, effectively disabling filesystem security for that data.

- Incorrect Web Server Ownership: Web server files should typically be owned by your user account, with the group set to the web server’s group (e.g., `www-data` on Debian/Ubuntu). The files should be read-only to the server, and only specific upload directories should be writable.

- Ignoring SUID/SGID Audits: Regularly scan for SUID/SGID files. A legitimate program with a vulnerability or a malicious SUID binary placed by an attacker can lead to a full system compromise.

Automation and Configuration Management

In modern DevOps environments, managing permissions manually is not scalable. Tools like Ansible, Puppet, and Chef are central to the latest Linux DevOps news. They allow you to define file permissions as code, ensuring that every server in your fleet has a consistent and correct security posture, which is automatically enforced.

Conclusion: Permissions as a Pillar of Security

We’ve journeyed from the simple `rwx` bits of the UGO model to the granular power of ACLs and the policy-driven enforcement of MAC systems. Mastering Linux file permissions is not a one-time task but an ongoing practice of vigilance and adherence to best practices. By understanding these layers of control, you can significantly harden your systems—whether it’s a personal Linux desktop, a Raspberry Pi project, or a fleet of cloud servers—against a wide array of threats.

The key takeaways are clear: always apply the principle of least privilege, use the right tool for the job (UGO, ACLs, or MAC), and make security auditing a regular part of your administrative routine. In the ever-evolving landscape of Linux news, a solid foundation in file permissions remains one of the most effective and timeless skills for ensuring system integrity and security.