Mastering Linux Security: A Deep Dive into iptables for Proactive Threat Mitigation

In the ever-evolving landscape of cybersecurity, robust network defense is not just a best practice—it’s a necessity. For system administrators managing Linux servers, from sprawling enterprise deployments on Red Hat Enterprise Linux to personal projects on a Raspberry Pi, the firewall remains the first line of defense. While newer technologies are emerging, the classic, powerful, and battle-tested iptables utility continues to be a cornerstone of Linux security. Recent Linux security news often highlights how misconfigured firewalls can be an open invitation for malware, including cryptocurrency miners and rootkits that exploit open, unmonitored ports.

Understanding iptables is a fundamental skill for anyone serious about Linux administration. It provides a granular, kernel-level packet filtering framework that, when configured correctly, can effectively thwart a wide range of network-based attacks. This article will serve as a comprehensive guide, moving from the core concepts of tables and chains to advanced techniques like rate-limiting and custom logging chains. Whether you are managing servers on Ubuntu, Debian, CentOS, or even exploring container security with Docker and Kubernetes, mastering iptables will empower you to build a more resilient and secure infrastructure. We will explore practical, real-world examples and best practices to help you harden your systems against unauthorized access and malicious activity.

The Core Architecture of iptables: Chains, Tables, and Targets

Before writing a single rule, it’s crucial to understand the logical structure of iptables. Its power lies in its organized approach to processing network packets. This architecture is built upon three fundamental concepts: tables, chains, and targets. This foundational knowledge is essential for anyone following Linux networking news and looking to implement effective security policies.

Tables and Chains Explained

iptables organizes rules into “tables” based on their purpose. While several tables exist, most day-to-day firewall management happens within the filter table, which is the default table for commands.

- filter: This is the most frequently used table. Its job is to decide whether a packet should be allowed to reach its destination, be blocked, or continue on its journey.

- nat (Network Address Translation): This table is used to modify the source or destination addresses of packets, commonly used for routing traffic through a gateway or masking private IP addresses.

- mangle: This table is for specialized packet alteration, such as modifying the Type of Service (TOS) field or the Time to Live (TTL) field of IP headers.

Within each table, rules are organized into “chains,” which are sequences of rules that a packet is evaluated against. The filter table contains three primary built-in chains:

- INPUT: Processes packets destined for the local server itself. This is where you control access to services like SSH, web servers (Apache, Nginx), or databases (PostgreSQL, MariaDB).

- OUTPUT: Processes packets generated by the local server. It allows you to control outbound connections.

- FORWARD: Processes packets that are being routed through the server. This is critical for systems acting as routers or gateways but is less relevant for a typical single-purpose server.

Targets: The Final Verdict

Each rule in a chain specifies criteria for a packet (e.g., source IP, destination port) and a “target,” which is the action to take if the packet matches. The most common targets are:

- ACCEPT: The packet is allowed to pass.

- DROP: The packet is silently discarded. The sender receives no notification, which can help slow down network scanners.

- REJECT: The packet is discarded, but an error message (e.g., “connection refused”) is sent back to the source.

- LOG: The packet information is logged to the kernel log, which can be viewed with tools like

dmesgorjournalctl. This is invaluable for Linux incident response and forensics.

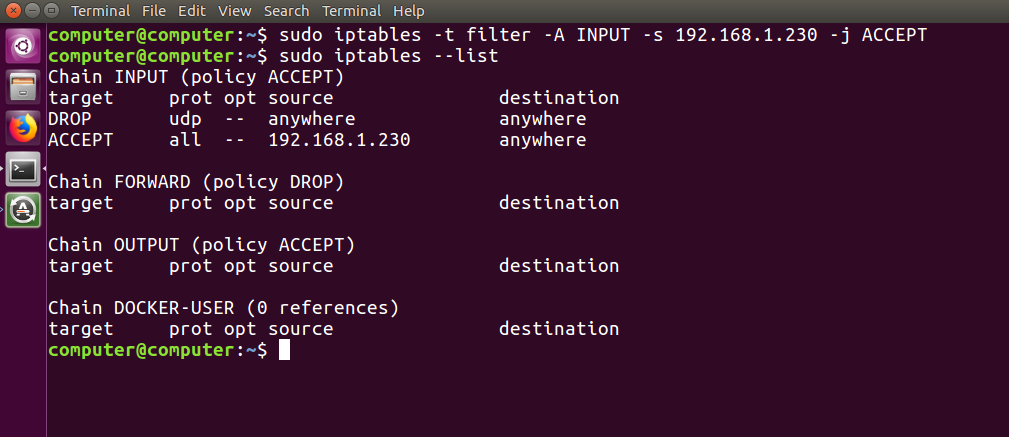

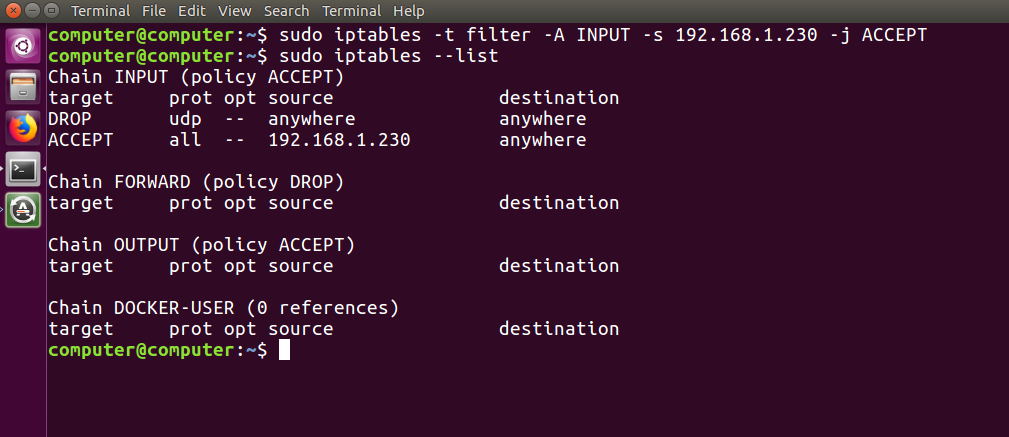

To see your current ruleset in the default filter table, you can use the following command. The flags -L (list), -v (verbose), and –n (numeric) provide a detailed and easy-to-read output.

# List all rules in the filter table with verbose and numeric output

sudo iptables -L -v -nFrom Theory to Practice: Crafting Your Initial iptables Ruleset

A secure firewall starts with a strong default policy. The industry best practice, often highlighted in Linux server news and security guides for distributions like Fedora, Arch Linux, and SUSE Linux, is to implement a “default deny” stance. This means you block everything by default and then explicitly open only the ports and services that are absolutely necessary.

Establishing a “Default Deny” Policy

By setting the default policy of the INPUT and FORWARD chains to DROP, you ensure that any packet not explicitly matched by an ACCEPT rule is discarded. This immediately reduces your server’s attack surface. While you can also set the OUTPUT chain to DROP for maximum security, it’s more common to leave it as ACCEPT on standard servers to avoid breaking application updates and other outbound communications.

# Set default policies to DROP for incoming and forwarded traffic

sudo iptables -P INPUT DROP

sudo iptables -P FORWARD DROP

# Set default policy to ACCEPT for outgoing traffic (common practice)

sudo iptables -P OUTPUT ACCEPT

# --- CRITICAL: Allow loopback traffic ---

# Services on the server often communicate with each other via the loopback interface (lo)

# Blocking this will break many applications.

sudo iptables -A INPUT -i lo -j ACCEPT

sudo iptables -A OUTPUT -o lo -j ACCEPTWarning: Once you set the INPUT policy to DROP, you will be locked out of your server unless you have rules to allow essential traffic, such as your current SSH session. Always ensure you have an allow rule for SSH before setting the default policy.

Allowing Essential Services with Stateful Inspection

With a default deny policy in place, you must now open the necessary ports. The most important rule to add is one that allows traffic for already established connections. This is known as stateful inspection and is a core feature of modern firewalls. The conntrack module tracks the state of connections, and the rule below allows return traffic for connections initiated by your server.

Next, you can add rules for specific services like SSH (port 22), HTTP (port 80), and HTTPS (port 443). This is a common requirement for any Linux web servers news covering Apache or Nginx deployments.

# Allow traffic from connections that are already established or related

sudo iptables -A INPUT -m conntrack --ctstate RELATED,ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT

# Allow new incoming SSH connections (TCP port 22)

sudo iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 22 -j ACCEPT

# Allow new incoming HTTP connections (TCP port 80)

sudo iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 80 -j ACCEPT

# Allow new incoming HTTPS connections (TCP port 443)

sudo iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 443 -j ACCEPT

# To save these rules on a Debian/Ubuntu system:

# sudo apt-get install iptables-persistent

# sudo netfilter-persistent save

# To save on a RHEL/CentOS/Rocky Linux system:

# sudo dnf install iptables-services

# sudo service iptables saveBeyond Basic Rules: Advanced iptables for Proactive Defense

A basic ruleset is a great start, but modern threats require more sophisticated defenses. iptables offers powerful modules that enable advanced techniques like rate-limiting and custom logging, which are critical for proactive Linux security news and hardening guides.

Rate Limiting to Prevent Brute-Force Attacks

Services exposed to the internet, especially SSH, are constant targets for automated brute-force attacks. You can use the recent module in iptables to track and block IPs that make too many connection attempts in a short period. This is a powerful technique for defending systems running on public cloud platforms like AWS, Azure, or DigitalOcean.

The following example creates a rule that drops new SSH connection attempts from any IP that has made more than 4 attempts in the last 60 seconds.

# This ruleset should be placed before the generic "allow SSH" rule.

# The order of rules matters!

# Add the IP of a new SSH connection to the 'SSH' list

sudo iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 22 -m conntrack --ctstate NEW -m recent --set --name SSH

# If an IP in the 'SSH' list tries to connect again within 60 seconds and has a hit count of over 4, drop it.

sudo iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 22 -m conntrack --ctstate NEW -m recent --update --seconds 60 --hitcount 4 --name SSH -j DROP

# This rule should come after the rate-limiting rules

sudo iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 22 -j ACCEPTThis approach effectively mitigates low-and-slow brute-force attacks without needing external tools like Fail2ban, handling the defense directly within the Linux kernel.

Logging and Dropping Suspicious Traffic

For effective Linux troubleshooting and security auditing, logging is paramount. Instead of just silently dropping all unwanted traffic, you can create a custom chain to first log suspicious packets and then drop them. This provides valuable insight into the types of attacks your server is facing. This technique is often discussed in Linux administration news as a way to gain better observability into network activity.

Here’s how to create a custom chain named LOG_AND_DROP and use it to log and then discard traffic from a specific malicious IP address.

# 1. Create a new custom chain

sudo iptables -N LOG_AND_DROP

# 2. Add a rule to the chain to log the packet with a custom prefix

# The log-level '4' corresponds to 'warning'

sudo iptables -A LOG_AND_DROP -j LOG --log-prefix "Suspicious Packet Dropped: " --log-level 4

# 3. Add a final rule to the chain to drop the packet

sudo iptables -A LOG_AND_DROP -j DROP

# 4. Now, use this chain in your INPUT chain for specific traffic

# For example, to block a known bad actor's IP address

sudo iptables -A INPUT -s 198.51.100.50 -j LOG_AND_DROP

# You can view these logs using journalctl

sudo journalctl -k | grep "Suspicious Packet Dropped"This modular approach keeps your main INPUT chain clean and makes your firewall logic easier to read and manage, a key principle in modern Linux DevOps news and infrastructure automation with tools like Ansible or Terraform.

Best Practices and the Road Ahead: iptables and nftables

Effectively managing a firewall involves more than just writing rules. It requires ongoing maintenance, clear documentation, and an awareness of the future of Linux networking. Adhering to best practices ensures your firewall remains effective and manageable over time.

Maintaining Your Ruleset

As your ruleset grows, it can become difficult to understand. Always use comments to document the purpose of complex rules. The comment module is perfect for this.

sudo iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 22 -m comment --comment "Allow standard SSH access" -j ACCEPT

For complex environments, avoid applying rules manually. Instead, manage your ruleset in a shell script or a configuration management tool like Puppet, Chef, or Ansible. This makes your firewall configuration version-controlled, repeatable, and less prone to human error. Regularly use iptables-save > /path/to/backup.rules to back up your configuration.

The Transition to nftables

It’s impossible to discuss iptables news without mentioning its successor, nftables. Introduced in the Linux kernel 3.13, nftables aims to replace the entire {ip,ip6,arp,eb}tables framework with a single, more efficient tool. It offers a superior syntax, atomic rule updates (preventing race conditions), and better performance. Most modern Linux distributions, including those covered in recent Debian news and Fedora news, now use nftables as the default backend.

Fortunately, these systems provide a compatibility layer, iptables-nft, which translates old iptables commands into the new nftables syntax. This means your existing scripts and knowledge are not obsolete. However, for new deployments, learning and using the native nft command is highly recommended. While iptables remains a critical skill due to its vast installed base, the future of Linux firewall news clearly belongs to nftables.

Conclusion

iptables remains an incredibly powerful and relevant tool in the arsenal of any Linux system administrator. While it may have a steep learning curve, its ability to provide granular, stateful packet filtering at the kernel level is unmatched for securing network services. By moving beyond a simple “allow all” policy and embracing a “default deny” strategy, you fundamentally improve your security posture.

We’ve covered the core architecture, practical implementation of a secure baseline, and advanced techniques like rate-limiting and custom logging to proactively defend against threats. The key takeaways are clear: always start with a restrictive policy, explicitly allow only what is necessary, leverage stateful inspection, and use logging to maintain visibility. As you continue to manage and deploy systems, from a simple Linux desktop to a complex Kubernetes cluster, these firewall principles will serve as the unshakable foundation of your server hardening strategy.