OpenGL on Linux Reimagined: How Zink’s Vulkan Layer is Outperforming Native Drivers

The Shifting Landscape of Linux Graphics: A New Era for OpenGL

For decades, OpenGL has been the cornerstone of 3D graphics on Linux. From the spinning cube desktop effects of the 2000s to modern video games and professional creative applications, it has been the go-to API for rendering complex scenes. However, the graphics world is in a constant state of evolution. The advent of modern, low-level APIs like Vulkan promised unprecedented control and performance, seemingly marking a slow sunset for the venerable OpenGL. Yet, in a fascinating turn of events, recent developments within the Mesa graphics library are not just keeping OpenGL relevant but are making it faster than ever, thanks to a translation layer named Zink. This groundbreaking project, which implements the OpenGL API on top of Vulkan, has now reached a critical milestone: in many scenarios, it is outperforming highly-optimized native OpenGL drivers. This development is not just an academic curiosity; it represents a fundamental architectural shift with profound implications for the entire Linux ecosystem, impacting everything from Linux gaming news and desktop environments like GNOME and KDE Plasma to the future of graphics driver development on distributions from Ubuntu news to Arch Linux news.

Core Concepts: Bridging Two Worlds from OpenGL to Vulkan

To understand the significance of Zink’s achievement, it’s essential to grasp the fundamental differences between native OpenGL drivers and a Vulkan-based translation layer. This architectural divergence is at the heart of this performance revolution.

Native OpenGL Drivers: The Traditional Approach

Traditional OpenGL drivers, such as radeonsi for AMD GPUs or iris for modern Intel GPUs, are complex, monolithic pieces of software. They are designed as sophisticated state machines that accept high-level OpenGL commands (e.g., “draw this triangle with this texture”) and translate them directly into the specific machine code for a particular GPU architecture. Over the years, these drivers have been meticulously optimized. However, their complexity makes them difficult to maintain and requires separate, dedicated development efforts for each hardware vendor. This can lead to inconsistencies and bugs across different platforms.

A developer starting an OpenGL project would typically initialize a context using a library like GLFW, which interfaces with these native drivers. The process is abstracted and relatively straightforward.

#include <GLFW/glfw3.h>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// Initialize the GLFW library

if (!glfwInit()) {

std::cerr << "Failed to initialize GLFW" << std::endl;

return -1;

}

// Set OpenGL version and profile

glfwWindowHint(GLFW_CONTEXT_VERSION_MAJOR, 3);

glfwWindowHint(GLFW_CONTEXT_VERSION_MINOR, 3);

glfwWindowHint(GLFW_OPENGL_PROFILE, GLFW_OPENGL_CORE_PROFILE);

// Create a windowed mode window and its OpenGL context

GLFWwindow* window = glfwCreateWindow(800, 600, "Native OpenGL Context", NULL, NULL);

if (!window) {

std::cerr << "Failed to create GLFW window" << std::endl;

glfwTerminate();

return -1;

}

// Make the window's context current

glfwMakeContextCurrent(window);

// Main loop

while (!glfwWindowShouldClose(window)) {

// Render here (e.g., glClear, glDrawArrays)

glClear(GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

// Swap front and back buffers

glfwSwapBuffers(window);

// Poll for and process events

glfwPollEvents();

}

glfwTerminate();

return 0;

}Zink: The Modern Translation Layer

Zink, a part of the open-source Mesa news project, takes a completely different approach. It is a Gallium3D driver that implements the full OpenGL API. However, instead of translating OpenGL calls into hardware-specific code, it translates them into Vulkan API calls. Vulkan is a modern, explicit, and low-overhead API that provides fine-grained control over the GPU. By targeting Vulkan, Zink effectively decouples the OpenGL implementation from the underlying hardware driver. As long as a system has a conformant Vulkan Linux news driver (e.g., RADV for AMD, ANV for Intel, or the proprietary NVIDIA driver), Zink can provide a complete OpenGL implementation. This dramatically simplifies the graphics stack, as hardware vendors can focus their efforts on perfecting a single, high-performance Vulkan driver, which in turn benefits all applications—both native Vulkan and OpenGL-via-Zink.

Implementation Details: How Zink Unlocks Performance

The idea of translating one API to another often implies a performance penalty due to overhead. For years, this was true for Zink. However, a series of recent, intensive refactoring efforts have flipped this assumption on its head, allowing Zink to reduce CPU overhead and leverage the efficiency of the underlying Vulkan driver more effectively than ever before.

Key Architectural Optimizations

The performance breakthrough stems from a deep re-architecture of Zink’s internals. A primary focus was on optimizing descriptor management—how the driver tells the GPU about resources like textures and buffers. By implementing a more sophisticated and efficient system, developers significantly reduced the CPU work required to prepare draw calls. Furthermore, optimizations in command buffer submission and state caching allow Zink to batch work more effectively and avoid redundant state changes, which are notoriously expensive in graphics programming. By leveraging Vulkan’s explicit synchronization and memory management primitives, Zink can often achieve a more optimal execution path than a legacy native driver burdened with decades of API design constraints. This is a major story in Linux performance news and shows the power of modern API design.

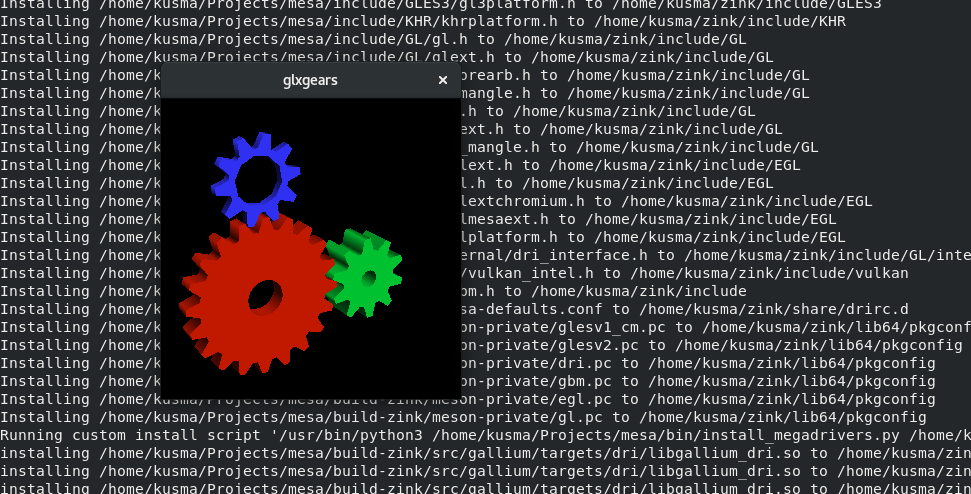

Forcing an Application to Use Zink

For developers and power users on distributions like Fedora news, Manjaro news, or any system with an up-to-date Mesa build, testing Zink is remarkably simple. It can be enabled on a per-application basis using a Mesa environment variable. This allows for direct A/B performance comparisons against the native driver without system-wide changes.

# Ensure you have the mesa-vulkan-drivers installed for your hardware

# On Debian/Ubuntu: sudo apt install mesa-vulkan-drivers

# On Fedora: sudo dnf install mesa-vulkan-drivers

# Run a game or application with the native OpenGL driver (default)

./my_opengl_game

# Now, run the same application forcing Zink as the OpenGL implementation

# MESA_LOADER_DRIVER_OVERRIDE=zink ./my_opengl_game

# For a more permanent solution for a specific game in Steam:

# Right-click the game -> Properties -> General -> Launch Options

# Add: MESA_LOADER_DRIVER_OVERRIDE=zink %command%This simple command is a powerful tool for anyone involved in Linux gaming news, from players on the Steam Deck to developers working with Proton and Wine, allowing them to tap into this new performance potential.

Advanced Techniques: Understanding the Translation Process

At its core, Zink’s job is to translate OpenGL’s state-based, implicit model into Vulkan’s explicit, object-based model. A key area where this translation is critical is in handling shaders.

From GLSL to SPIR-V

OpenGL applications use the OpenGL Shading Language (GLSL). The driver compiles this high-level, C-like code at runtime. Vulkan, on the other hand, consumes a pre-compiled intermediate representation called SPIR-V. Zink must therefore take the incoming GLSL source code, compile it, and translate it into a valid SPIR-V module that the underlying Vulkan driver can execute. This process is handled by libraries like NIR (a Mesa-internal intermediate representation) and `glslang` or other compilers. The efficiency of this translation is crucial for performance, especially in applications that dynamically generate or modify shaders.

Here is a simple example of a vertex and fragment shader in GLSL that Zink would process.

// -- Vertex Shader --

#version 330 core

layout (location = 0) in vec3 aPos;

layout (location = 1) in vec2 aTexCoord;

out vec2 TexCoord;

uniform mat4 model;

uniform mat4 view;

uniform mat4 projection;

void main()

{

gl_Position = projection * view * model * vec4(aPos, 1.0);

TexCoord = aTexCoord;

}

// -- Fragment Shader --

#version 330 core

out vec4 FragColor;

in vec2 TexCoord;

uniform sampler2D ourTexture;

void main()

{

FragColor = texture(ourTexture, TexCoord);

}Zink’s ability to perform this translation efficiently and correctly is a testament to the maturity of the Mesa compiler infrastructure, a topic frequently covered in Linux development news and of interest to anyone working with GCC news or LLVM news.

Best Practices and Future Outlook

While Zink’s performance is now competitive and often superior, it’s important to know when and how to use it, and what its success means for the future of the Linux desktop and server ecosystems.

When Should You Use Zink?

The answer is increasingly “most of the time,” but some nuance remains. Zink is particularly beneficial in the following scenarios:

- Modern Hardware: Systems with excellent, well-maintained Vulkan drivers (common for modern AMD, Intel, and NVIDIA GPUs) are the prime candidates.

- Gaming and Emulation: Many older games and emulators that use OpenGL can see significant performance and stability improvements, as they can now leverage the highly active development of Vulkan drivers. This is central to the Steam Deck news narrative.

- Future-Proofing: For developers starting new OpenGL projects, targeting an environment where Zink runs well ensures the application will benefit from the unified Vulkan driver path going forward.

- Bug Workarounds: If an application has a rendering bug with a native OpenGL driver, running it on Zink may resolve the issue, as it uses a completely different code path.

Verifying which driver is active is simple with standard Linux tools, making it easy for administrators and users on any distribution, from Rocky Linux news to Pop!_OS news, to diagnose their graphics stack.

# This command will show which OpenGL renderer is currently in use.

# For native AMD: "AMD Radeon RX 7900 XTX (radeonsi, navi31, LLVM 15.0.7, DRM 3.49, 6.1.9-arch1-1)"

# When using Zink: "Zink (Mesa 23.0.0-devel) (AMD Radeon RX 7900 XTX (RADV navi31))"

glxinfo | grep "OpenGL renderer string"The Road to a Unified Graphics Stack

Zink’s success is a major step toward a unified graphics driver model on Linux. The long-term vision is a future where hardware vendors focus solely on producing a single, high-quality, open-source Vulkan driver. Legacy APIs like OpenGL would exist as robust, performant, and universally compatible translation layers on top. This simplifies the entire stack, reduces the maintenance burden for both kernel and userspace developers, and provides a more consistent and stable experience for users of desktop environments like GNOME news and KDE Plasma news. This shift, a key topic in Linux kernel news, promises a more resilient and performant future for all graphical applications on Linux.

Conclusion: A Watershed Moment for OpenGL on Linux

The recent performance breakthroughs of the Zink OpenGL-on-Vulkan driver are more than just an incremental improvement; they represent a watershed moment for the Linux graphics ecosystem. The fact that a translation layer can now consistently compete with and even surpass a mature, native driver validates the architectural bet on Vulkan as the future-proof foundation for graphics. This achievement, born from the collaborative open-source spirit of the Mesa project, ensures that the vast library of OpenGL applications will not only survive but thrive for years to come. For developers, gamers, and everyday users across the spectrum of Linux distributions, this news signals the arrival of a simpler, more unified, and higher-performance graphics stack, solidifying Linux’s position as a first-class platform for high-performance computing.