The Linux Boot Process Demystified: A Deep Dive from UEFI to systemd

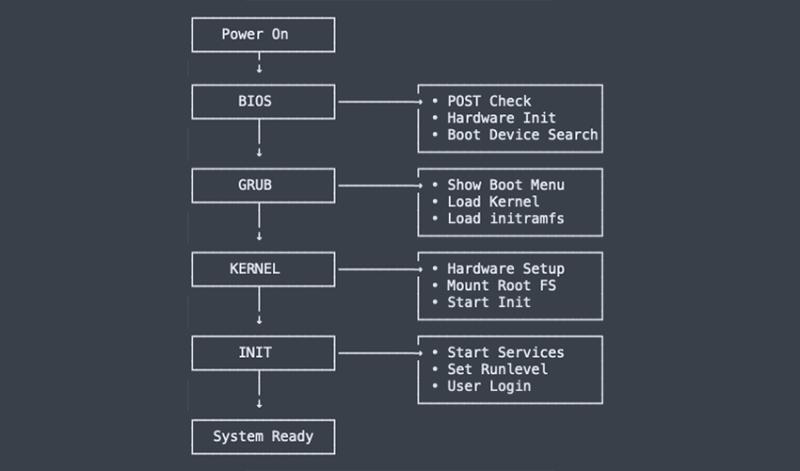

The journey from a powered-off machine to a fully functional Linux desktop or server is a complex and elegant dance of software components. For many users, this process is a black box—a series of fleeting text messages or a simple logo that appears before the login screen. However, for system administrators, DevOps engineers, and curious enthusiasts, understanding the Linux boot process is a fundamental skill. It’s the key to troubleshooting critical errors, optimizing performance, and securing the very foundation of your system. In this comprehensive article, we will demystify the modern Linux boot sequence, tracing the path from the initial power-on signal through the firmware, bootloader, kernel, and finally, to the user space orchestrated by systemd.

The Initial Spark: Firmware and Bootloader Hand-off

Before Linux even enters the picture, the system’s hardware needs to be initialized. This is the responsibility of the firmware, which has seen a significant evolution over the past decade, profoundly impacting the Linux boot process news and best practices.

UEFI: The Modern Firmware Standard

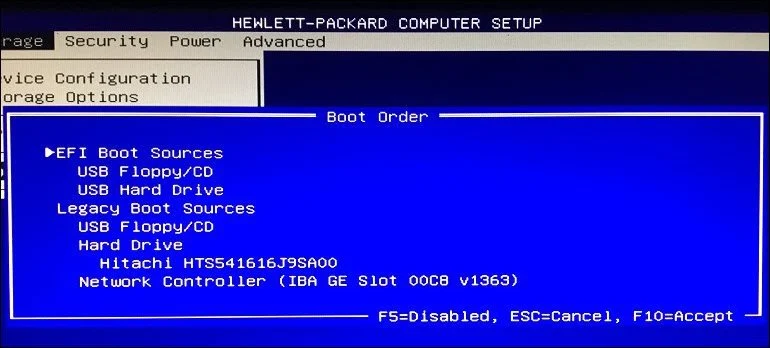

For years, the Basic Input/Output System (BIOS) was the de facto standard for PC firmware. However, its limitations, such as the 2TB disk partition limit with Master Boot Record (MBR), prompted the industry to move towards a more robust solution: the Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI). Modern systems running everything from Ubuntu news to Arch Linux news overwhelmingly use UEFI.

When you power on a UEFI-based system, it performs a Power-On Self-Test (POST) to check for basic hardware functionality. After the POST is successful, the UEFI firmware doesn’t just look for a bootable sector at the beginning of a disk like BIOS did. Instead, it consults its boot manager, which reads configuration data stored in NVRAM. This data points to bootloader files located on a special, standardized partition called the EFI System Partition (ESP). The ESP is typically formatted with a FAT32 filesystem, making it accessible to the firmware and cross-platform compatible.

You can inspect and manage UEFI boot entries directly from within Linux using the efibootmgr tool, a crucial piece of knowledge for any Linux administration news follower.

The Bootloader’s Grand Entrance: GRUB and systemd-boot

The bootloader is the bridge between the firmware and the Linux kernel. Its primary job is to load the kernel and an initial RAM disk (initramfs) into memory and then transfer execution control to the kernel. The most common bootloader in the Linux world is the GRand Unified Bootloader, version 2 (GRUB2).

GRUB2 is powerful and highly configurable. It can boot multiple operating systems, handle different filesystems, and allows for kernel parameter modification at boot time. Its configuration is typically generated automatically but resides in /boot/grub/grub.cfg. Examining this file reveals how the boot process is structured.

### BEGIN /etc/grub.d/10_linux ###

menuentry 'Ubuntu' --class ubuntu --class gnu-linux --class gnu --class os $menuentry_id_option 'gnulinux-simple-...' {

recordfail

load_video

gfxmode $linux_gfx_mode

insmod gzio

insmod part_gpt

insmod ext2

set root='hd0,gpt2'

if [ x$feature_platform_search_hint = xy ]; then

search --no-floppy --fs-uuid --set=root --hint-bios=hd0,gpt2 --hint-efi=hd0,gpt2 --hint-baremetal=ahci0,gpt2 1234abcd-1234-abcd-1234-1234567890ab

else

search --no-floppy --fs-uuid --set=root 1234abcd-1234-abcd-1234-1234567890ab

fi

linux /boot/vmlinuz-6.5.0-14-generic root=UUID=... ro quiet splash

initrd /boot/initrd.img-6.5.0-14-generic

}

### END /etc/grub.d/10_linux ###In this snippet, the two most important lines are:

linux ...: This line specifies the path to the Linux kernel image (vmlinuz-...) and passes critical parameters to it, such as the location of the root filesystem (root=UUID=...) and options likero(read-only initial mount) andquiet splash.initrd ...: This line points to the initial RAM disk image (initrd.img-...), which we’ll explore next.

An alternative, simpler bootloader gaining popularity, especially in the Fedora news and Arch Linux communities, is systemd-boot. It’s a lightweight UEFI boot manager that reads simple configuration files directly from the ESP, offering a less complex alternative to GRUB for UEFI-only systems.

Waking the Core: Kernel Initialization and the Initial RAM Disk

Once the bootloader has loaded the kernel and initramfs into memory and passed control, the Linux kernel’s own startup sequence begins. This phase is critical for initializing the system’s core components and preparing to mount the real root filesystem.

The Kernel Unpacked

The kernel file, often named vmlinuz, is a compressed self-extracting executable. The first thing it does is decompress itself into memory. It then proceeds to initialize fundamental subsystems: memory management, process scheduling, and the CPU. It parses the boot parameters passed by GRUB to understand where to find its root filesystem and what other configuration options to apply. During this early stage, the kernel loads a minimal set of built-in drivers required to access the console and essential hardware. You can view the messages from this entire process using the dmesg command, a cornerstone of Linux troubleshooting news.

The Crucial Role of Initramfs/Initrd

A modern Linux system presents a classic chicken-and-egg problem: to mount the root filesystem (e.g., on an LVM volume, an encrypted LUKS partition, or a Btrfs subvolume), the kernel needs specific drivers or modules. But those modules reside on the root filesystem, which isn’t mounted yet! The solution is the initial RAM filesystem (initramfs).

The initramfs is a small, gzipped cpio archive loaded into memory by the bootloader. The kernel mounts this temporary in-memory filesystem as its initial root. The initramfs contains a minimal set of directories, utilities (like busybox), and most importantly, the kernel modules needed to access the real root filesystem (e.g., nvme, ext4, dm-crypt, btrfs). Scripts within the initramfs load these modules, discover the storage devices, unlock encrypted volumes if necessary, and finally mount the real root filesystem. Once the real root is mounted, the initramfs pivots, and the system’s startup process continues from the now-accessible permanent storage.

Tools like dracut (used by RHEL, Fedora, CentOS) and mkinitcpio (used by Arch Linux) are responsible for generating this crucial file. You can inspect its contents to see what’s included.

# On a Fedora/RHEL-based system

# List the contents of the initramfs for the currently running kernel

lsinitrd /boot/initramfs-$(uname -r).img

# On a Debian/Ubuntu-based system

# Create a temporary directory and extract the contents

mkdir ~/initramfs-contents

cd ~/initramfs-contents

unmkinitramfs /boot/initrd.img-$(uname -r) .Orchestrating the System: The systemd Init Process

With the real root filesystem mounted, the kernel executes the first user-space program: /sbin/init. On virtually all modern Linux distributions, from Debian news to SUSE Linux news, /sbin/init is a symbolic link to systemd. This marks the hand-off from the kernel space to the user space.

PID 1: The Parent of All Processes

systemd starts as Process ID (PID) 1. This is significant because PID 1 is the ancestor of all other processes on the system. It is responsible for bringing the system up to a usable state by starting services, mounting filesystems, and setting up networking. It also acts as the ultimate process manager, adopting any orphaned processes and ensuring the system can be shut down or rebooted gracefully. This central role is why systemd news is so closely watched in the Linux community.

Understanding systemd Targets and Units

systemd operates on the concept of “units.” A unit is a configuration file that describes a resource systemd can manage, such as a service (.service), a mount point (.mount), or a device (.device). The most important type of unit for the boot process is the “target” (.target). A target unit groups other units together to bring the system to a specific state, analogous to the runlevels in the older SysVinit system.

During boot, systemd activates the default.target, which is usually a symlink to either multi-user.target (for a command-line server environment) or graphical.target (for a desktop environment with a display manager). systemd reads the dependencies for this target and starts all required units, leveraging parallelization to significantly speed up the boot process compared to older, sequential init systems. You can easily check your default target.

# Check the current default target

systemctl get-default

# Set the default target to multi-user (disables GUI on next boot)

sudo systemctl set-default multi-user.target

# Set the default target back to graphical

sudo systemctl set-default graphical.targetOne of the most powerful features systemd provides for Linux performance news and analysis is the systemd-analyze suite. It allows you to precisely measure and diagnose boot performance.

# Get a summary of boot time

systemd-analyze

# See how long each service took to start

systemd-analyze blame | head -n 10

# Generate an SVG plot of the boot process

systemd-analyze plot > boot_plot.svgWhen Things Go Wrong: Debugging and Optimization

A solid understanding of the boot process is most valuable when a system fails to start. Knowing where to look for clues is half the battle in Linux troubleshooting news.

Essential Troubleshooting Tools

When a boot fails, these tools are your best friends:

dmesg: This command prints the kernel ring buffer. If the boot process fails very early (during kernel initialization), booting from a live USB and examining the logs of the failed system can reveal kernel panics or critical driver failures.journalctl: The systemd journal is the central logging system for modern Linux. The commandjournalctl -bshows all logs from the current boot. Even more powerfully,journalctl -b -1shows logs from the *previous* boot, which is invaluable for diagnosing a system that fails to complete startup and forces a reboot.- GRUB Rescue Mode: If you see a

grub rescue>prompt, it means GRUB was loaded but couldn’t find its configuration file or the specified kernel. This often indicates a misconfiguredgrub.cfgor an issue with the/bootpartition itself.

For example, to see only the error-level messages from the previous failed boot, you can use this command from a recovery environment or after a successful reboot:

# Show all messages with priority "error" or higher from the previous boot

journalctl -b -1 -p errBest Practices for a Healthy Boot

- Keep Systems Updated: Regular updates to the kernel, GRUB, and systemd, as reported in Linux kernel news and distro-specific channels like Pop!_OS news or Rocky Linux news, often contain critical bug fixes and security patches related to the boot process.

- Backup Bootloader Config: Before making manual changes to

/etc/default/grubor other boot-related files, always make a backup. - Monitor Boot Times: Periodically run

systemd-analyze blameto identify new services that may be slowing down your boot. - Have a Rescue Plan: Always have a live USB of your favorite distribution handy. It provides a working environment from which you can

chrootinto your broken system to repair the bootloader, rebuild the initramfs, or edit configuration files.

Conclusion: From Power to Prompt

The modern Linux boot process is a sophisticated sequence that balances flexibility, power, and speed. It begins with the UEFI firmware initializing the hardware and handing off to a bootloader like GRUB. The bootloader then loads the Linux kernel and a temporary initramfs, which contains the necessary drivers to mount the real root filesystem. Finally, the kernel executes systemd as PID 1, which orchestrates the startup of all user-space services and brings the system to a fully operational state, whether it’s a headless server in the cloud or a high-performance Linux desktop news environment running GNOME or KDE Plasma.

By understanding these stages and the tools available for inspection and troubleshooting—such as efibootmgr, systemd-analyze, and journalctl—you are empowered to diagnose problems, optimize performance, and manage your Linux systems with greater confidence and expertise. The next time you power on your machine, take a moment to appreciate the intricate and robust process happening behind the scenes.