Unlocking a New Era of Security: A Deep Dive into Hardware-Wrapped Keys in the Linux Kernel

In the ever-evolving landscape of cybersecurity, protecting data at rest remains a cornerstone of any robust security strategy. For years, the Linux ecosystem has provided powerful tools for encryption, from full-disk encryption with LUKS and dm-crypt to granular, file-level protection with fscrypt. While effective, these methods have traditionally relied on software-based key management, where master keys are protected by user-supplied passphrases or keyfiles stored on disk. This approach, though secure, presents challenges, particularly for unattended systems and in scenarios involving physical device theft. A recent breakthrough in the Linux kernel is set to change this paradigm by introducing native support for hardware-wrapped encryption keys, fundamentally enhancing how Linux protects sensitive data.

This advancement leverages the Trusted Platform Module (TPM), a dedicated security chip present in most modern computers, to anchor filesystem encryption directly to the hardware. By “wrapping” cryptographic keys with the TPM, the kernel can ensure that data can only be decrypted on the specific machine it was encrypted on, even if an attacker has physical possession of the storage drive. This article provides a comprehensive technical exploration of this new feature, covering the underlying concepts, its implementation with fscrypt, practical applications, and best practices for system administrators. This is significant Linux hardware news that will impact distributions from Fedora and Ubuntu to enterprise platforms like Red Hat and SUSE.

The Foundations of Linux Encryption and Hardware Security

To fully appreciate the significance of hardware-wrapped keys, it’s essential to understand the existing encryption frameworks in Linux and the role of hardware security modules like the TPM. These technologies form the bedrock upon which this new capability is built.

A Refresher on fscrypt and dm-crypt

Linux offers two primary approaches to data-at-rest encryption:

- Full-Disk Encryption (FDE): Typically implemented using

dm-cryptand the Linux Unified Key Setup (LUKS) standard, FDE encrypts an entire block device (like a hard drive partition). When the system boots, the user must provide a passphrase to unlock the entire volume. This is a powerful “all-or-nothing” approach, but it doesn’t offer granular control over individual files or directories. - File-Based Encryption (FBE): Implemented by the

fscryptframework directly within filesystems like ext4, Btrfs, and F2FS. Unlike FDE,fscryptencrypts individual files and directories, each with its own unique key. These file keys are, in turn, encrypted by a master key. This allows for multi-user security, where different users can have different encrypted home directories, each unlocked only upon their login. The master key has traditionally been protected by the user’s login passphrase.

The new kernel developments focus on enhancing fscrypt by changing how this master key is protected, moving from software-based protection to hardware-anchored security.

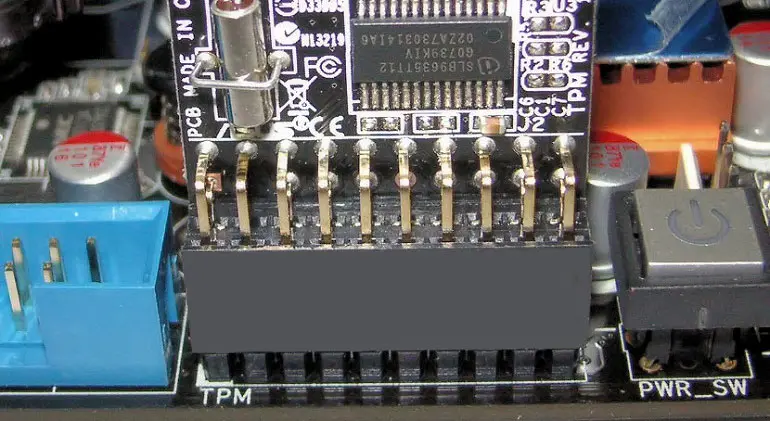

Introducing the Trusted Platform Module (TPM)

A Trusted Platform Module (TPM) is a specialized, tamper-resistant microcontroller built into a computer’s motherboard, conforming to an international standard. Its primary purpose is to perform cryptographic operations in a secure, isolated environment. Key features of a TPM include:

- Secure Key Generation and Storage: The TPM can generate cryptographic keys and ensure that certain keys, like the Storage Root Key (SRK), can never leave the chip.

- Sealing: It can encrypt data (or “seal” it) in a way that it can only be decrypted (“unsealed”) when the computer is in a specific, known-good state.

- Attestation: It can cryptographically prove the system’s hardware and software state to a remote party.

The “state” of the system is measured and recorded in Platform Configuration Registers (PCRs). During boot, the firmware, bootloader, kernel, and other critical components have their cryptographic hashes extended into these PCRs. By sealing a key to a specific set of PCR values, you can ensure it’s only released if the boot process hasn’t been tampered with. Most modern Linux distributions, including the latest from the Fedora news and Ubuntu news cycles, ship with tools to interact with the TPM.

You can check for the presence of a TPM 2.0 device on your system with a simple command.

# Check for the existence of a TPM device. The presence of /dev/tpm0 is a good sign.

ls -l /dev/tpm*

# For more detailed information, install and use the tpm2-tools package

# On Fedora/RHEL/CentOS/Rocky Linux:

# sudo dnf install tpm2-tools -y

# On Debian/Ubuntu/Linux Mint:

# sudo apt-get install tpm2-tools -y

# Query the TPM for its fixed properties and capabilities

tpm2_getcap properties-fixedHow Hardware-Wrapped Keys Work with fscrypt

The core innovation lies in integrating the kernel’s cryptographic subsystem with the TPM’s capabilities. Instead of just relying on a passphrase, fscrypt can now offload the security of its master key to the hardware, a major piece of Linux kernel news with wide-ranging implications for Linux security news.

The “Wrapping” Concept Explained

The term “key wrapping” is a specific form of encryption. In this context, it means that the fscrypt master key (which is generated in software) is encrypted using a public key whose private counterpart, the Storage Root Key (SRK), is permanently locked inside the TPM. This encrypted blob, the “wrapped key,” can be safely stored on the main filesystem.

The process works as follows:

- Wrapping (Encryption):

fscryptgenerates a master key. It then passes this key to the kernel, which communicates with the TPM driver. The TPM encrypts the master key with its non-exportable SRK and returns the wrapped key. This wrapped key is then stored on disk. The plaintext master key is purged from memory. - Unwrapping (Decryption): When access to the encrypted files is needed (e.g., at user login or system boot), the user-space tools ask the kernel to unlock the files. The kernel reads the wrapped key from disk and sends it to the TPM. The TPM uses its internal SRK to decrypt it and returns the plaintext master key to the kernel’s keyring. This key is never exposed to user-space and is used to decrypt the per-file keys as needed.

The critical security guarantee is that the unwrapping operation can only be performed by the exact same TPM that originally wrapped the key. If you move the hard drive to another computer, the new machine’s TPM will not have the correct SRK and will be unable to decrypt the wrapped key, rendering the data inaccessible.

This conceptual Python example illustrates the principle of wrapping and unwrapping, using a hypothetical library to represent the TPM’s functions.

import os

from cryptography.hazmat.primitives.ciphers import Cipher, algorithms, modes

from cryptography.hazmat.backends import default_backend

# This is a conceptual example to illustrate the process.

# A real implementation would use kernel APIs and a TPM driver.

class HypotheticalTPM:

"""A mock class to simulate TPM key wrapping functions."""

def __init__(self):

# In a real TPM, this key would be hardware-bound and non-exportable.

self._storage_root_key = os.urandom(32)

self._backend = default_backend()

def wrap_key(self, key_to_wrap: bytes) -> bytes:

"""Simulates encrypting a key with the TPM's internal key."""

iv = os.urandom(16)

cipher = Cipher(algorithms.AES(self._storage_root_key), modes.CFB(iv), backend=self._backend)

encryptor = cipher.encryptor()

wrapped_key = encryptor.update(key_to_wrap) + encryptor.finalize()

print("TPM: Wrapping key...")

# The IV is prepended to the ciphertext for unwrapping.

return iv + wrapped_key

def unwrap_key(self, wrapped_key_blob: bytes) -> bytes:

"""Simulates decrypting a key using the TPM's internal key."""

iv = wrapped_key_blob[:16]

ciphertext = wrapped_key_blob[16:]

cipher = Cipher(algorithms.AES(self._storage_root_key), modes.CFB(iv), backend=self._backend)

decryptor = cipher.decryptor()

print("TPM: Unwrapping key...")

unwrapped_key = decryptor.update(ciphertext) + decryptor.finalize()

return unwrapped_key

# --- Main Logic ---

tpm = HypotheticalTPM()

secret_data = b"Critical configuration for our production Linux server."

# 1. Generate a one-time data encryption key (like an fscrypt master key)

data_key = os.urandom(32)

# 2. Use the TPM to wrap this data key

wrapped_data_key = tpm.wrap_key(data_key)

print(f"Safely stored wrapped key on disk: {wrapped_data_key.hex()[:40]}...")

# 3. The original data_key is now discarded from application memory.

del data_key

# --- Later, when access is needed ---

# 4. The application asks the TPM to unwrap the key

try:

unwrapped_data_key = tpm.unwrap_key(wrapped_data_key)

print("Key unwrapped successfully!")

# Now `unwrapped_data_key` can be used to decrypt the actual files.

# In a real scenario, this key would live in the kernel keyring.

except Exception as e:

print(f"Failed to unwrap key: {e}")

Practical Applications and System Configuration

The theoretical benefits of hardware-wrapped keys translate into tangible improvements for specific, high-impact use cases, especially in server and embedded environments. This development is a boon for Linux server news and Linux administration news.

Use Case: Securing Unattended Servers and IoT Devices

A classic dilemma for administrators is securing servers that must be able to reboot without human intervention. Traditional full-disk encryption requires someone to enter a passphrase at the boot console, which is impractical for remote data centers or fleets of IoT devices. Hardware-wrapped keys solve this elegantly.

By sealing the fscrypt master key to the system’s PCR values, a server can be configured to automatically unlock its encrypted data volumes on boot, but only if the boot chain (firmware, bootloader, kernel) is unmodified. If an attacker attempts to boot a malicious OS to tamper with the data, the PCR values will not match, and the TPM will refuse to unseal the key. This provides a high degree of security for unattended reboots after power failures or scheduled patching, a feature highly anticipated in the Debian news and CentOS news communities for their stability-focused use cases.

You can inspect the current PCR values on your system to see how the boot state is measured.

# View the current Platform Configuration Register (PCR) values for the SHA256 bank.

# Each PCR index corresponds to a different stage of the boot process.

# For example, PCRs 0-7 typically measure firmware, option ROMs, and the bootloader.

tpm2_pcrread sha256A Look Ahead at Configuration

As this is a new kernel-level feature, user-space tooling like fscryptctl will need to be updated to expose this functionality to users and administrators. While the exact commands are still being finalized, we can anticipate what the workflow might look like for setting up a TPM-protected encrypted directory.

# NOTE: This is a hypothetical command sequence based on expected future tooling.

# The actual flags and syntax may vary in the final implementation.

# 1. Ensure the system has necessary tools.

# This version of fscrypt would need to be compiled with TPM support.

sudo dnf install fscrypt tpm2-tools -y # On a Fedora-based system

# 2. Perform the one-time setup for the filesystem if not already done.

sudo fscrypt setup /mnt/data

# 3. Create a new "protector" that is linked to the TPM.

# This command would instruct fscrypt to generate a master key and have it wrapped

# by the specified TPM device. The wrapped key would be stored in fscrypt's metadata.

sudo fscryptctl add_protector /mnt/data/encrypted_docs --source=tpm --tpm-device=/dev/tpm0

# 4. Create and encrypt the target directory using the new TPM protector.

mkdir /mnt/data/encrypted_docs

fscrypt encrypt /mnt/data/encrypted_docs --protector=/mnt/data/encrypted_docs

# 5. When the user logs in or the system boots, the unlock process would be

# handled by a PAM module or a systemd service, which would request the key

# from the kernel, triggering the TPM unwrapping operation automatically.

# Manual unlocking would look similar to today:

# fscrypt unlock /mnt/data/encrypted_docs

Best Practices, Pitfalls, and Performance

While powerful, deploying TPM-based encryption requires careful planning to avoid potential issues and maximize security. As this feature rolls out to distributions like Arch Linux and openSUSE, understanding these considerations will be key.

Best Practices and Security Hardening

- Defense in Depth: For maximum security, don’t rely solely on the TPM. You can configure policies that require both the TPM state to be correct and a user-provided PIN to release the key. This provides two-factor protection.

- Secure the Bootchain: The security of PCR-based sealing depends entirely on the integrity of the components being measured. Use UEFI Secure Boot to ensure that only signed, trusted bootloaders and kernels can run.

- Recovery Keys are Non-Negotiable: A TPM is a single point of failure. Hardware can fail, or you might legitimately need to migrate data. Always create a separate, passphrase-based recovery key for your encrypted data and store it securely offline.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

The most significant risk with TPM-sealed keys is the “bricked system” scenario. If you seal a key to a specific set of PCR values and then perform a legitimate system update (e.g., a BIOS/UEFI update or a kernel upgrade), the PCR values will change on the next boot. The TPM will correctly detect this change and refuse to unseal the key, locking you out of your data. This is why a recovery key is absolutely critical. Modern implementations aim to be smarter about this, for example by only sealing to PCRs that measure the bootloader and not the kernel, which changes frequently.

Performance Considerations

A common concern with new security features is their impact on performance. Fortunately, the effect of using hardware-wrapped keys is minimal and largely confined to the initial unlock operation.

- Unlock Time: The cryptographic operations performed by the TPM to unwrap a key are slightly slower than decrypting a key with a CPU. This may add a few hundred milliseconds to the login or boot process.

- I/O Throughput: Once the master key is unwrapped and loaded into the kernel keyring, all subsequent file encryption and decryption operations are completely unaffected. They continue to be handled by the CPU, leveraging highly optimized hardware acceleration instructions (like AES-NI). The runtime performance of reading and writing encrypted files is identical to traditional

fscryptsetups.

In summary, the performance trade-off is a negligible one-time cost at unlock for a massive gain in key security.

Conclusion: A Major Step Forward for Linux Security

The integration of hardware-wrapped key support directly into the Linux kernel is a landmark achievement in the platform’s security evolution. By bridging the gap between the robust fscrypt filesystem encryption framework and hardware security modules like the TPM, Linux is gaining a powerful new defense against physical attacks and providing a secure, elegant solution for unattended systems. This feature moves the root of trust for data encryption from something you know (a passphrase) to something you have (a specific, trusted piece of hardware).

For system administrators, DevOps engineers, and security professionals, this development offers a compelling new tool for hardening servers, IoT fleets, and personal workstations. As user-space tools and major distributions begin to incorporate this functionality, we can expect to see it become a new standard for data protection. Keep an eye on Linux kernel news and updates from your favorite distribution, whether it’s Pop!_OS, Manjaro, or an enterprise platform, as this powerful security feature becomes more accessible to everyone.