The New Era of Linux Observability: From Classic Commands to eBPF Superpowers

The Evolution of Linux Performance and Observability

In today’s complex IT landscape, from sprawling cloud-native applications on Kubernetes to high-performance bare-metal servers, understanding what’s happening inside a Linux system is more critical than ever. The days of simply checking CPU load with `top` are long gone. We’ve entered a new era of deep system analysis, moving beyond traditional monitoring to true observability. Monitoring tells you when something is wrong; observability lets you ask why. This shift is powered by a new generation of tools and kernel technologies that provide unprecedented insight into system behavior, a key topic in recent Linux observability news. Whether you manage servers running on Debian, Ubuntu, or a Red Hat derivative like Rocky Linux or AlmaLinux, these advancements are changing the game for system administrators, DevOps engineers, and performance experts.

This article explores the modern landscape of Linux observability, tracing the evolution from classic command-line utilities to the revolutionary capabilities of eBPF. We’ll cover the foundational tools, dive into the powerful new paradigms, and demonstrate how to build a modern observability stack to achieve peak performance and reliability for any Linux workload.

The Foundation: Classic Tools and Kernel Interfaces

Before jumping into the latest trends, it’s essential to appreciate the foundational tools that have served the Linux community for decades. These utilities are still indispensable for quick, ad-hoc analysis and form the bedrock of system administration. The latest Linux commands news often includes updates and improvements to these trusted tools.

Timeless Utilities: `top`, `iostat`, and `vmstat`

Tools like `top`, `htop`, `iostat`, `vmstat`, and `netstat` are the first-responders for any performance issue. They provide a high-level overview of system resources, including CPU usage, memory consumption, disk I/O, and network activity. For example, `htop` offers a more user-friendly and detailed view of running processes than the traditional `top` command, making it a staple on nearly every modern Linux desktop and server, from Arch Linux to openSUSE.

While powerful for a quick snapshot, their primary limitation is that they present aggregated data. They can tell you that disk I/O is high, but they can’t easily tell you *which specific process* is causing it or *which files* it’s accessing in real-time. This is where their role as a starting point ends and the need for deeper tools begins.

The Source of Truth: The `/proc` and `/sys` Filesystems

Most classic monitoring tools are simply user-friendly front-ends for the data exposed by the Linux kernel through virtual filesystems, primarily `/proc` and `/sys`. The `/proc` filesystem presents information about processes and kernel status as readable files. For instance, `/proc/meminfo` contains a detailed breakdown of memory usage, which is what commands like `free` and `vmstat` parse.

Directly querying these files can be a powerful way to get raw data for custom scripts, a common practice in Linux shell scripting. This approach avoids the overhead of running a separate command and allows for precise data extraction.

#!/bin/bash

# A simple script to parse /proc/meminfo and display free memory percentage

# Read total and available memory (in kB) from /proc/meminfo

MEM_TOTAL=$(grep MemTotal /proc/meminfo | awk '{print $2}')

MEM_AVAILABLE=$(grep MemAvailable /proc/meminfo | awk '{print $2}')

# Check if we got the values

if [ -z "$MEM_TOTAL" ] || [ -z "$MEM_AVAILABLE" ]; then

echo "Error: Could not read memory information from /proc/meminfo."

exit 1

fi

# Calculate the percentage of available memory

PERCENT_AVAILABLE=$(awk "BEGIN {printf \"%.2f\", ($MEM_AVAILABLE / $MEM_TOTAL) * 100}")

echo "Total Memory: ${MEM_TOTAL} kB"

echo "Available Memory: ${MEM_AVAILABLE} kB"

echo "Percentage Available: ${PERCENT_AVAILABLE}%"This script demonstrates a fundamental concept in Linux administration news: using core system interfaces for automation and monitoring. While useful, this method is still based on polling—reading data at intervals—and can miss fleeting, intermittent problems.

The Game Changer: eBPF and Programmable Observability

The most significant development in Linux kernel news over the past decade for observability is arguably the extended Berkeley Packet Filter (eBPF). eBPF is a revolutionary technology that allows sandboxed programs to run directly within the Linux kernel without changing kernel source code or loading kernel modules. This provides a safe, efficient, and incredibly powerful way to observe the inner workings of the system.

What Makes eBPF So Powerful?

eBPF programs can be attached to various hooks within the kernel, such as tracepoints, kprobes (kernel function entry/exit), and even network packet processing paths. When an event triggers one of these hooks, the attached eBPF program executes.

- Performance: Because eBPF code runs in-kernel, it avoids the expensive context switches between kernel and user space that traditional tracing tools like `strace` require.

- Safety: Before loading, an eBPF program is put through a rigorous in-kernel verifier that checks for unsafe operations, such as infinite loops, out-of-bounds memory access, or illegal instructions. This ensures a buggy or malicious eBPF program cannot crash the kernel.

- Programmability: It allows developers to write custom logic to collect and summarize data directly at the source, providing insights that were previously impossible to obtain.

Making eBPF Accessible: BCC and bpftrace

Writing raw eBPF programs can be complex. Fortunately, higher-level frameworks have emerged to simplify the process. The BPF Compiler Collection (BCC) and `bpftrace` are two of the most popular.

- BCC: A toolkit for creating efficient kernel tracing and manipulation programs, often using Python or C++ as a front-end. It includes a rich library of ready-to-use tools like `execsnoop` (snoops `exec()` calls), `opensnoop` (traces `open()` calls), and `biolatency` (summarizes block I/O latency as a histogram).

- bpftrace: Provides a high-level tracing language inspired by `awk` and `DTrace`. It allows for powerful one-liners and scripts to be written directly on the command line, making ad-hoc performance analysis incredibly fast and intuitive. This is a must-have tool for anyone following Linux troubleshooting news.

Here’s a practical `bpftrace` one-liner to trace all new processes being executed on the system, showing the command and its process ID (PID):

# This command requires root privileges to run

bpftrace -e 'tracepoint:syscalls:sys_enter_execve { printf("%-16s %-6d\n", comm, pid); }'Imagine debugging a misbehaving application in a complex Docker Linux news environment. You could use `bpftrace` to see exactly which system calls a specific container is making, helping you pinpoint file access issues, network connection problems, or unexpected process executions with minimal overhead.

Building a Modern Observability Stack

While eBPF tools are phenomenal for deep, real-time analysis, a complete observability strategy requires a system for collecting, storing, and visualizing data over time. This is where the “three pillars of observability”—metrics, logs, and traces—come into play, supported by a suite of powerful open-source tools.

The Three Pillars: Metrics, Logs, and Traces

- Metrics: Time-series numerical data, such as CPU utilization, memory usage, or network throughput. This is the domain of tools like Prometheus.

- Logs: Timestamped, immutable records of discrete events. In modern Linux systems, `journald` is the primary log manager, and its logs can be aggregated with tools like Loki or the ELK Stack (Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana).

- Traces: A representation of the lifecycle of a request as it flows through a distributed system. Tools like Jaeger and Zipkin are leaders in this space.

Prometheus and Grafana: The De Facto Standard for Metrics

In the world of Linux monitoring news, Prometheus has emerged as the dominant open-source solution for metrics. It operates on a pull model, scraping metrics from HTTP endpoints on target systems. For Linux hosts, the `node_exporter` is the standard agent for exposing a vast array of system-level metrics, from CPU and memory statistics to filesystem and network details.

This data is then stored in Prometheus’s time-series database and can be queried using its powerful query language, PromQL. For visualization, Grafana is the perfect partner, allowing you to build rich, interactive dashboards.

Here is a snippet from a `prometheus.yml` configuration file showing how to scrape metrics from a Linux server running `node_exporter`:

# prometheus.yml

scrape_configs:

- job_name: 'node_exporter'

static_configs:

- targets: ['your_linux_server_ip:9100']Once data is flowing, you can use PromQL in Grafana to ask sophisticated questions. For example, to find the per-second rate of context switches over the last 5 minutes, you could use the following query:

# PromQL query

rate(node_context_switches_total[5m])This combination of Prometheus and Grafana provides a robust foundation for any modern Linux server news or DevOps workflow, often deployed and managed using tools mentioned in Ansible news or Terraform.

Best Practices and The Future of Linux Observability

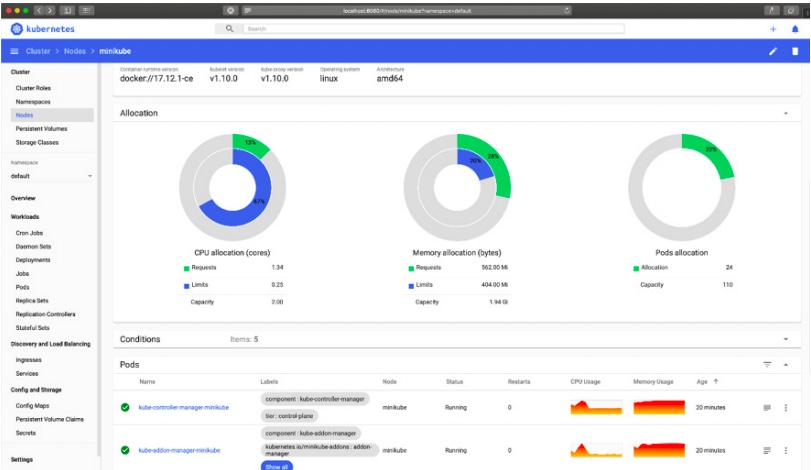

As systems grow more complex, particularly with the rise of containers and microservices, our observability strategies must adapt. The ephemeral nature of containers managed by Kubernetes or Podman presents a unique challenge, but also an opportunity to leverage new tools.

Observability in a Containerized World

In a containerized environment, it’s not enough to monitor the host. You need visibility into individual containers. The Linux kernel’s cgroups, which provide resource isolation for containers, also expose detailed metrics. The Prometheus `node_exporter` includes a cgroup collector, and dedicated tools like Google’s `cAdvisor` can provide even more granular container-level data. This is a critical topic in Kubernetes Linux news.

Furthermore, service meshes like Istio and Linkerd are becoming central to observability in microservices architectures. They automatically capture metrics, logs, and traces for all network traffic between services, providing a level of visibility that is nearly impossible to achieve manually.

Key Takeaways and Best Practices

- Use the Right Tool for the Job: Start with classic tools like `htop` and `iostat` for a quick overview. When you need to dig deeper, reach for the power of `bpftrace` or BCC.

- Embrace eBPF: Invest time in learning eBPF-based tools. They are the future of high-performance Linux troubleshooting and observability.

- Build a Unified Stack: Don’t rely on one pillar of observability. Combine metrics (Prometheus), logs (Loki), and traces (Jaeger) for a complete picture of your system’s health.

- Automate Everything: Use configuration management tools like Ansible, Puppet, or SaltStack to deploy and manage your observability agents and platforms consistently across your entire fleet.

Conclusion: A Clearer View Than Ever Before

The landscape of Linux observability has undergone a profound transformation. We have moved from periodic, high-level snapshots to a world of continuous, low-overhead, and deeply programmable analysis. The rise of eBPF has unlocked the “black box” of the kernel, allowing us to ask detailed questions about system behavior without sacrificing performance. When combined with a modern, integrated stack like Prometheus and Grafana, these capabilities give engineers unprecedented visibility into their systems.

Whether you are a system administrator keeping a fleet of servers running on a stable release like Debian or a developer optimizing an application on a cutting-edge distro like Fedora, mastering these modern tools is no longer optional—it’s essential. By embracing this new era of observability, we can build more resilient, performant, and reliable systems on the powerful foundation that Linux provides.